Long before the pyramids rose in Egypt and centuries before the great temples of Mesopotamia reached the sky, another civilization flourished quietly along the fertile floodplains of the Indus River. The Indus Valley Civilization, often called the Harappan Civilization after one of its earliest discovered cities, thrived between 2600 BCE and 1900 BCE across what is now Pakistan and northwest India. With its orderly cities, sophisticated drainage systems, and thriving trade networks, the Indus Valley was not merely a prehistoric settlement—it was one of the earliest great urban cultures of humanity.

But what was it like to live there? What did ordinary men, women, and children do each day as the sun rose over the river? To peer into daily life in the Indus Valley is to rediscover an ancient rhythm of existence, where the murmur of marketplaces, the hum of potter’s wheels, and the songs of farmers working in the fields wove together the fabric of society. Archaeology gives us fragments: bricks, beads, seals, skeletons, and tools. From these, scholars reconstruct the tapestry of life, allowing us to imagine a world that, though thousands of years old, feels strangely familiar.

The City as a Living Organism

Daily life in the Indus Valley unfolded within cities that were marvels of planning and ingenuity. Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa, Dholavira, and Lothal were not chaotic settlements but carefully designed urban centers. Streets were laid out in straight lines, intersecting at right angles, creating a grid-like pattern that modern planners admire even today.

Most homes were built of baked bricks, uniform in size, giving the neighborhoods a sense of order. Houses varied in scale: some were modest, with one or two rooms, while others stretched into larger, multi-room dwellings with courtyards and private wells. This variation suggests a society that, while not completely egalitarian, may have been more balanced than other ancient civilizations where palaces dwarfed the homes of common people.

Each home opened onto the street but also connected inward to family spaces. Many had staircases, hinting at second stories. And most remarkably, nearly every home was connected to an advanced drainage system—covered sewers ran beneath the streets, carrying waste away from the city. To live in the Indus Valley was to be part of a community that valued cleanliness, order, and public well-being.

Waking to the Rhythm of the River

For most inhabitants, daily life was shaped by the natural cycles of the Indus River and its tributaries. The river was a source of water, fertile soil, fish, and transportation. Farmers rose early to tend to fields of wheat, barley, peas, and sesame. Cotton was also cultivated here, making the Indus people the world’s earliest known cotton growers.

Agriculture was labor-intensive but rewarding. Oxen pulled wooden plows through the soil, while farmers sowed seeds by hand. Irrigation channels diverted water where it was needed, though the annual floods of the Indus provided much of the fertility naturally. Men, women, and children likely shared in this work, ensuring that the city’s granaries were filled.

Granaries themselves were massive, brick-built structures where surplus grain was stored—perhaps redistributed by administrators or used in trade. Life revolved around the agricultural calendar: planting, harvesting, storing, and waiting for the river’s flood. Each season brought its duties, and the rhythm of work bound the community together.

Home and Hearth

Inside the homes of the Indus Valley, daily life revolved around family, food, and domestic crafts. Hearths were common, where meals were prepared with grains, lentils, and vegetables. Clay ovens and fire pits were used for cooking, while pottery vessels stored water, milk, or oil.

Mealtime was likely communal, with family members sharing food from large platters. Though little direct evidence survives, it is believed that dairy products—milk, yogurt, ghee—played a role in their diet, alongside bread made from wheat and barley. Fruits like dates and melons may have been common, along with meat from cattle, goats, and poultry, though evidence suggests meat was consumed less frequently than plant-based foods.

Domestic crafts also filled the home. Women and men alike may have spun cotton into thread, woven textiles, or crafted beads. Children learned skills from their elders, not in formal schools but through apprenticeship within the family unit. Life at home was practical, industrious, and bound by the rhythms of necessity.

Clothing and Adornment

The Indus Valley people dressed simply yet with elegance. Cotton, abundant in the region, was woven into garments—an innovation that would later spread across the ancient world. Men likely wore a type of wrapped cloth, similar to a dhoti, while women may have draped themselves in long garments or skirts. Some figurines suggest women wore elaborate headdresses or hair ornaments, adorned with beads and jewelry.

Jewelry was not reserved for the wealthy. Archaeological finds reveal beads made of carnelian, lapis lazuli, steatite, and shell. Gold and silver ornaments also existed, though rarer. Both men and women seem to have worn jewelry, from necklaces and bangles to earrings and anklets. Children, too, were adorned—perhaps to ward off evil or as signs of affection.

Adornment was not mere vanity; it was an expression of identity, artistry, and perhaps social belonging. The craftsmanship of Indus jewelers speaks of a people who valued beauty and had the skills to achieve it.

The World of Work and Trade

Not everyone in the Indus Valley was a farmer. Cities bustled with artisans, traders, and craftsmen whose skills supported both local life and long-distance commerce. Potters shaped clay into vessels of striking symmetry, some plain, others painted with geometric designs or animal motifs. Weavers worked cotton into textiles that may have been exported to distant lands.

Stone carvers produced seals—small, square tablets engraved with animals and mysterious script. These seals, used to mark goods and property, are among the civilization’s most iconic artifacts. They also hint at trade, for seals traveled alongside goods across regions.

The Indus Valley was not isolated. Trade linked it to Mesopotamia, Persia, and Central Asia. Archaeologists have found Indus seals in Mesopotamian cities, and Mesopotamian records mention trade with “Meluhha,” believed to be the Indus region. Exports may have included cotton textiles, beads, and timber, while imports brought metals like tin, silver, and precious stones.

For the trader walking the streets of Mohenjo-Daro, life was cosmopolitan, connected not just to neighbors but to distant cultures hundreds of miles away.

Religion and Ritual in Daily Life

The spiritual life of the Indus Valley is one of its greatest mysteries. Unlike Mesopotamia and Egypt, no grand temples or towering statues dominate the archaeological record. Instead, spirituality seems woven into daily spaces and objects.

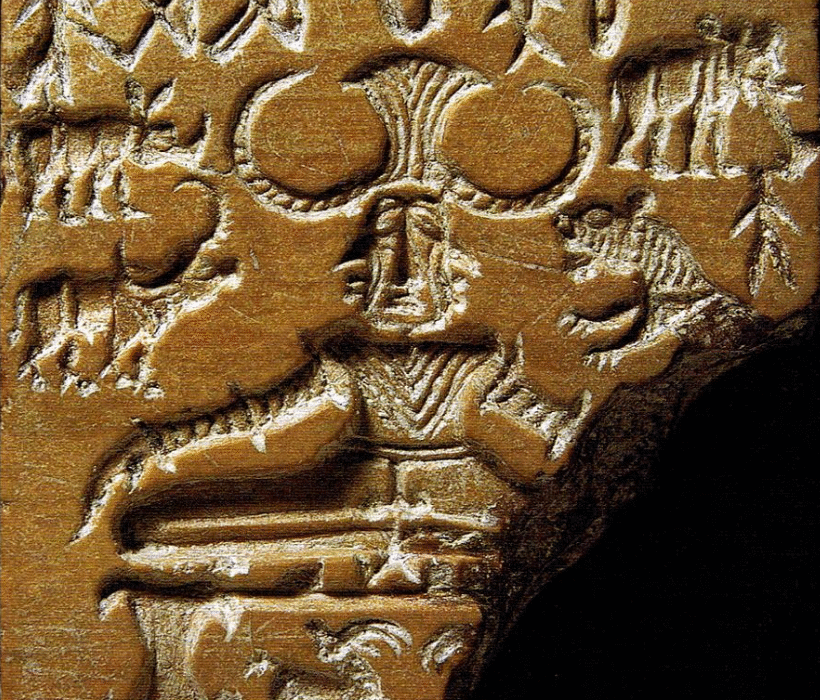

Small figurines, often of mother goddesses, suggest a belief in fertility and the cycles of life. The “proto-Shiva” seal, depicting a horned figure seated in a yogic posture, hints at early traditions that may have influenced later Hinduism. Ritual bathing, too, appears central: the Great Bath at Mohenjo-Daro suggests water was linked with purity, renewal, or spiritual practice.

At the household level, small altars or ritual objects may have been used in daily devotion. Religion in the Indus Valley may have been less about centralized authority and more about community and family practices, binding people through shared symbols rather than monumental temples.

Children, Play, and Learning

Children in the Indus Valley were not forgotten in the archaeological record. Terracotta figurines of animals, wheeled carts, and whistles shaped like birds suggest a lively world of play. Clay marbles and small toys point to childhood joys not so different from today’s.

Learning likely took place within the family or community. Boys may have learned farming, craftwork, or trade from their fathers, while girls were taught weaving, pottery, and household skills from their mothers. But toys suggest that play, imagination, and curiosity were also part of growing up. Childhood was not merely preparation for adulthood—it had its own place in daily life.

Health and Hygiene

One of the most remarkable features of the Indus Valley was its emphasis on hygiene. Almost every house had access to bathing areas and drains, while public baths and wells ensured the community’s cleanliness. This concern for sanitation was far ahead of its time and may have contributed to the overall health of the population.

Bones and skeletons tell another part of the story. Evidence shows that the Indus people faced diseases like arthritis, tuberculosis, and dental problems. Injuries from work and infections were common. Yet their advanced urban planning likely reduced outbreaks of waterborne diseases compared to less organized settlements.

Healing practices remain largely unknown, but amulets and charms suggest a blend of practical and spiritual remedies. Just as today, health was a daily concern, shaped by both environment and culture.

The Role of Women

Women in the Indus Valley appear to have played significant roles in family, economy, and spiritual life. Figurines of mother goddesses suggest reverence for female fertility and power. Jewelry and ornaments show that women were celebrated for their beauty and individuality.

Archaeological evidence also suggests that women may have engaged in crafts such as bead-making or textile production. In households, they were likely central to food preparation, child-rearing, and the maintenance of hygiene. Yet their presence in religious symbolism hints that women were not confined to domestic roles alone—they were integral to the cultural imagination of the civilization.

Music, Art, and Expression

Life in the Indus Valley was not only practical but also expressive. Musical instruments such as flutes and drums have been found, suggesting that music accompanied rituals, celebrations, or simple moments of leisure. Dancing figurines show that movement and rhythm were celebrated arts, bringing vitality to festivals or gatherings.

Artistic expression was evident in pottery designs, seal carvings, and beadwork. Though often geometric and symbolic, these works reveal creativity, imagination, and perhaps storytelling traditions. Life was not only about survival; it was also about beauty, joy, and shared culture.

Governance and Social Order

What kind of government guided the daily lives of Indus Valley people? Unlike Egypt’s pharaohs or Mesopotamia’s kings, the Indus Valley leaves behind no monumental palaces or royal tombs. This has led scholars to believe that governance may have been more decentralized, perhaps led by councils or local assemblies rather than powerful monarchs.

The uniformity of brick sizes, city planning, and weights and measures suggests strong regulation and collective organization. Daily life was likely shaped by laws and customs that emphasized fairness, order, and cooperation. For the ordinary citizen, this meant living in a society where public welfare, cleanliness, and trade were carefully maintained.

Decline and Legacy

By 1900 BCE, the great cities of the Indus Valley began to decline. Climate change, shifting rivers, and overuse of land may have disrupted agriculture. Trade networks weakened, and cities were gradually abandoned. Yet daily life did not vanish overnight—villages endured, traditions persisted, and the people adapted.

The legacy of the Indus Valley survives in many ways. Cotton cultivation, urban planning, sanitation, bead-making, and even elements of spiritual practice may have influenced later South Asian cultures. The story of daily life in the Indus Valley is not a lost chapter—it is a foundation upon which countless later traditions were built.

Conclusion: The Humanity of the Indus Valley

To walk through the streets of Mohenjo-Daro in imagination is to hear the echoes of an ancient humanity not so different from our own. Farmers sowing fields, women weaving cloth, children playing with clay toys, merchants haggling in bustling markets, and priests pouring water in sacred baths—all these lives formed the heartbeat of a civilization.

Daily life in the Indus Valley was not about kings or battles, but about people. Ordinary, extraordinary people who built one of the world’s earliest urban societies with ingenuity, resilience, and vision. Their drains still whisper of hygiene, their beads of beauty, their seals of identity, and their toys of joy.

The Indus Valley reminds us that history is not only made by rulers and monuments but by the rhythm of everyday life—the shared meals, the laughter of children, the labor of hands, and the quiet rituals of home. In studying their world, we rediscover our own humanity reflected in theirs, carried forward across millennia by the enduring story of life.