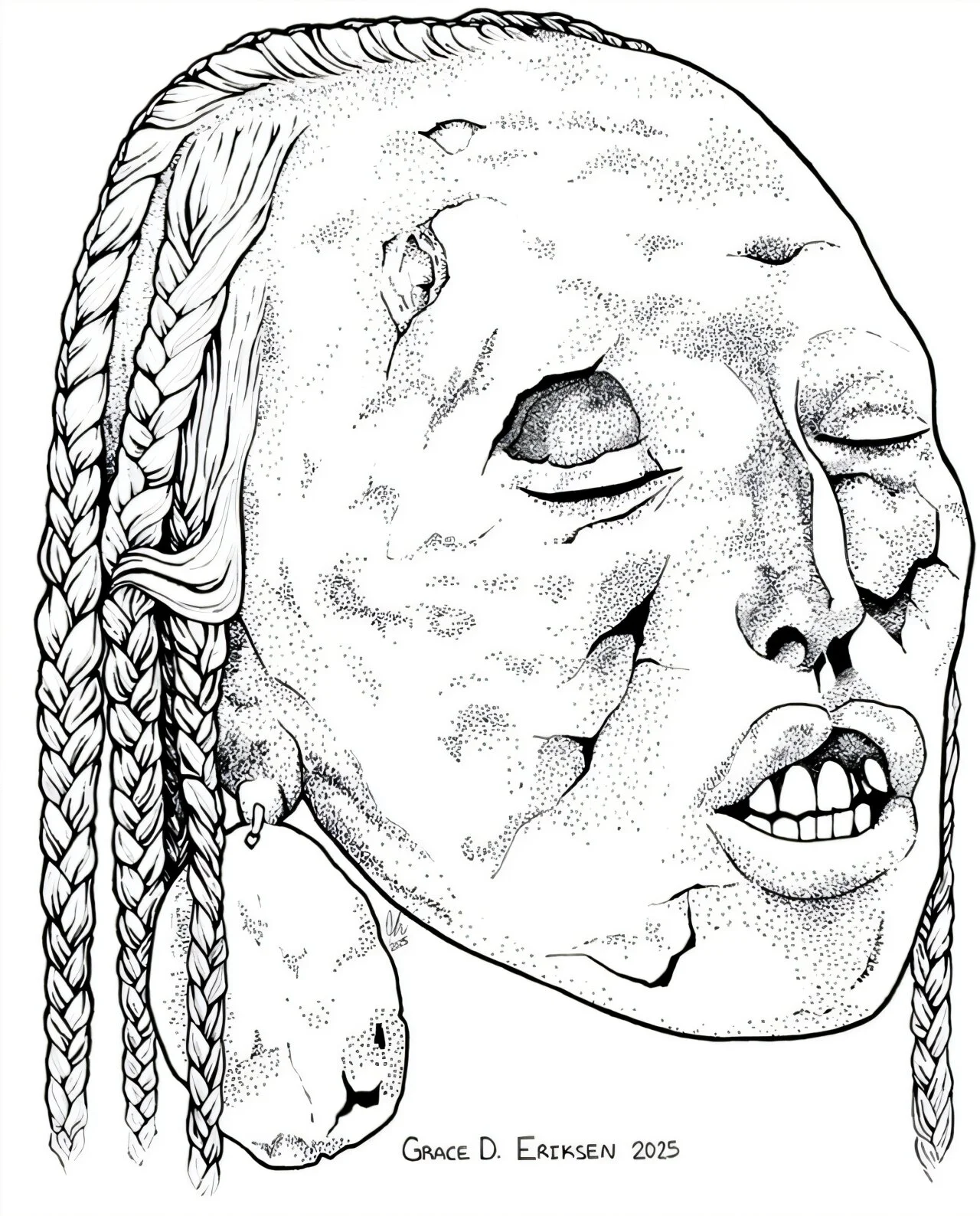

The story begins with a single image in a 2021 museum catalog. It was the face of a man preserved as a Peruvian trophy head, his skin coated in a golden waxy patina, his mouth set in an unmistakable L-shape. To most viewers, he might have appeared simply as one more artifact in a European museum. But to Dr. Beth Scaffidi, the head revealed something far more unusual. Through careful analysis of these images, she diagnosed the individual with a cleft lip and palate, making him the first identified Andean trophy head with this congenital condition and one of only six known cases of CLP in ancient human remains from the region.

Her study, published in Ñawpa Pacha, transforms what might have been a static display into the beginning of a complex, deeply human story.

The Journey of a Head Across Continents and Centuries

The head that drew Dr. Scaffidi’s attention had already traveled far by the time she encountered it. According to the catalog, it originated from “Ocucace,” assumed to reference Hacienda Ocucaje in Paracas, Peru. It had been imported by Pierre Langlois and, since 2004, displayed at the Musée de Grenoble in France.

Like many trophy heads from the Andes, this one carried traces of deliberate preparation. Its dimensions—44 by 16 by 21 centimeters—suggest a carefully preserved object. Its skin bore a rigid, glassy surface rather than the soft, suede-like texture usually found on desert-preserved heads. Something about its treatment had altered it, but by whom and when remained uncertain.

“The trophy head appeared to have had a preservative applied that made the skin glassy, rigid, and cracked, instead of the sueded texture most trophy heads found in the desert have,” Dr. Scaffidi elaborates. She continues with measured caution. “I cannot tell without chemical testing whether this was a preservative applied to cure the skin in ancient times or whether this was a preservative applied by the various collectors and museums that held it…The Paracas area does have tar pits, and this could have been applied as a preservative, but there is no other evidence (to the best of my knowledge) for using tar in mortuary ritual.”

The copper earrings the man wore point toward a southern Peruvian coastal origin during the height of trophy head collecting, sometime between 300 BC and 750 CE. Yet other details remain out of reach. “Direct osteological examination is needed to verify sex and age-at-death, but I suspect that the well-deserved facial and muscle tissues would obscure observations of key cranial features,” Dr. Scaffidi explains.

Even so, one feature stood out clearly—his cleft lip and palate.

A Marked Face in an Ancient World

The presence of a cleft lip and palate carries a long and complicated history. Clefts form during fetal development when the upper jaw and nasal cavities fail to fully fuse. In many societies, both ancient and modern, this difference has been met with fear, stigma, or marginalization. Infants with clefts were sometimes shunned or even unable to survive early childhood.

But ancient Peru tells a more nuanced story.

Archaeologists have uncovered around 30 vessels depicting men with suspected cleft lips dressed in garments of power—jewelry, head wrappings, or symbols of healing and shamanic roles. Historical testimony adds further depth. Roman-Catholic priest Father Blas Valera wrote that Peruvian individuals with this malformation often held low-level priestly positions. Among the Moche, those with congenital facial differences were believed to be shielded from supernatural harm.

The copper earrings on the trophy head may hint at similar status—elite in life, symbolic in death, or both. Though impossible to confirm, the possibility invites a new kind of empathy toward the individual. His difference might not have been a curse. It might have been a calling.

A Future Written in Hair, Bone, and Teeth

As with many ancient remains, definitive answers will depend on what science can still retrieve from the body itself. Dr. Scaffidi sees the potential clearly. “ …Minimally-destructive isotopic analysis of hair, bone, and teeth formed at various ages could give us clarity on whether this individual’s dietary and residence history was similar to other individuals in the population or different.”

Such tests could reveal where he grew up, how far he traveled, and whether his life aligned with others who held special positions in his society. Each result would add context to his story, transforming speculation into grounded understanding.

But before those discoveries can unfold, another challenge looms: repatriation.

When the Dead Become Objects and Objects Become Ancestors

Dr. Scaffidi speaks candidly about the obstacles. “I would like for the public to know that, while repatriation to descendant communities is a goal all archaeologists and bioarchaeologists share, there are many obstacles to meaningfully returning skeletal remains.”

She outlines the difficulties step by step. Museums must inventory their collections, but remains are often mixed, mislabeled, or lack documentation. “This is difficult as individuals are often commingled with other individuals over time (e.g., two left forearms in the box for one individual), and documentation can be missing or insufficient to verify the country of provenience.”

Funding, too, is scarce. “There is often little or no funding available for the critical work of inventorying legacy collections… Granting agencies are much more interested in supporting new excavations as opposed to funding studies and inventories of legacy human remains, assuming they have all been thoroughly studied. However, many skeletons have not yet been inventoried or studied at all, and those steps are pre-requisites to any repatriation efforts.”

Even after careful sorting and study, uncertainty may remain. “Finally, even after skeletons are inventoried, it can be difficult to verify the country or region of provenience where documentation is missing, or to identify the appropriate descendant community…”

The story of this single trophy head demonstrates how uncertain these boundaries can be. It resurfaced not through archaeological work but in a modern art exhibit, where it appeared as one object among many—despite being a human life reduced to a display.

As Dr. Scaffidi notes, this shows how “the human body can flux back and forth between beloved dead ancestor and object depending on the cultural context of the viewer.”

Why This Discovery Matters

This study reminds us that behind every artifact lies a person. The man with the cleft lip lived, breathed, struggled, and was shaped by the cultural forces of his time. His head traveled across centuries and continents, passing through hands that saw him as a relic, a curiosity, or a work of art.

But today, science and scholarship allow him to be seen again as a human being.

By identifying his CLP, Dr. Scaffidi has expanded our understanding of ancient Andean societies, revealing how they perceived physical differences and hinting at the complex roles people with congenital conditions may have held. Her work also underscores the ethical responsibilities tied to human remains in museums and private collections, urging institutions to confront the challenges of documentation and repatriation.

Ultimately, this research matters because it restores humanity to someone long treated as an object. It invites us to look more closely, to question our assumptions, and to remember that the past is filled not with artifacts, but with lives.

More information: Beth K. Scaffidi, Celebrating Cleft Lip? Osteological and Artistic Evidence of Lip Deformity in a Trophy Head Individual from Southern Peru, Ñawpa Pacha (2025). DOI: 10.1080/00776297.2025.2565062