In the icy grip of Siberia’s Altai Mountains, a mummified body lay entombed for over two millennia—silent, still, and encased in permafrost. But thanks to cutting-edge digital imaging technology and a team of international archaeologists, the tattoos that once decorated this Iron Age individual’s skin have been brought back to life in remarkable detail.

For the first time, scientists can peer beneath the frostbitten veil of time to witness ancient body art not merely as symbols, but as the work of skilled individuals—prehistoric tattoo artists whose creativity, technique, and learning curves now speak to us across the ages.

Unlocking a 2,000-Year-Old Mystery with Modern Technology

Tattooing is an ancient practice, one that likely predates writing and possibly even agriculture. Yet, because skin rarely survives the ravages of time, the evidence for prehistoric tattooing is frustratingly sparse. The so-called “ice mummies” of the Altai Mountains—buried deep within frozen tombs known as kurgans—offer a rare exception. Their bodies, preserved by nature’s most ruthless freezer, still bear the inked marks of a culture long gone.

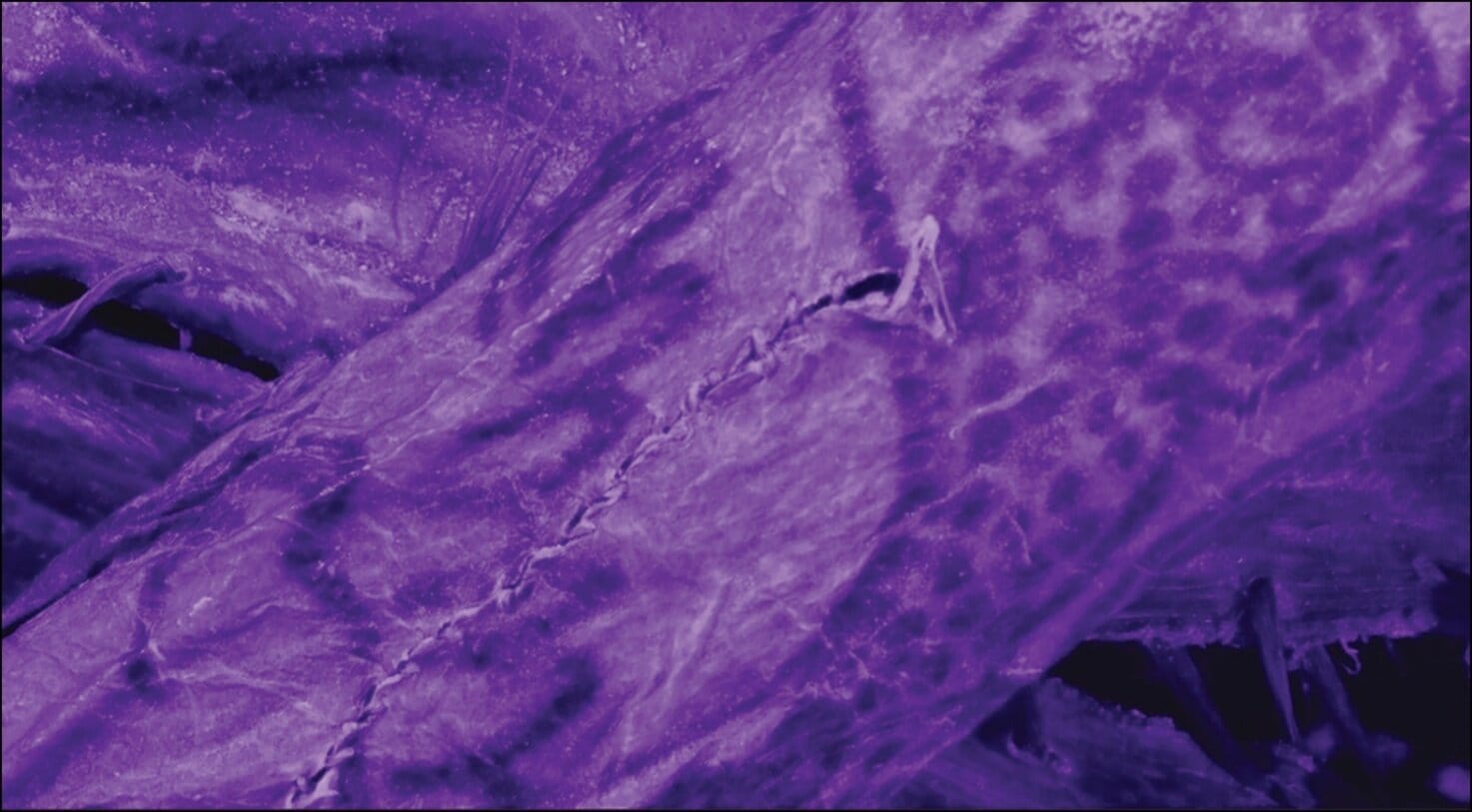

Now, using high-resolution near-infrared imaging with sub-millimeter accuracy, researchers have examined the tattoos of one such mummy belonging to the Pazyryk culture—Iron Age nomadic pastoralists known for their elaborate burial rites and enigmatic tattoo art. The results, published in the journal Antiquity, provide an unprecedented view into the technical mastery and human stories behind these ancient tattoos.

Moving Beyond Symbolism to Skill and Craft

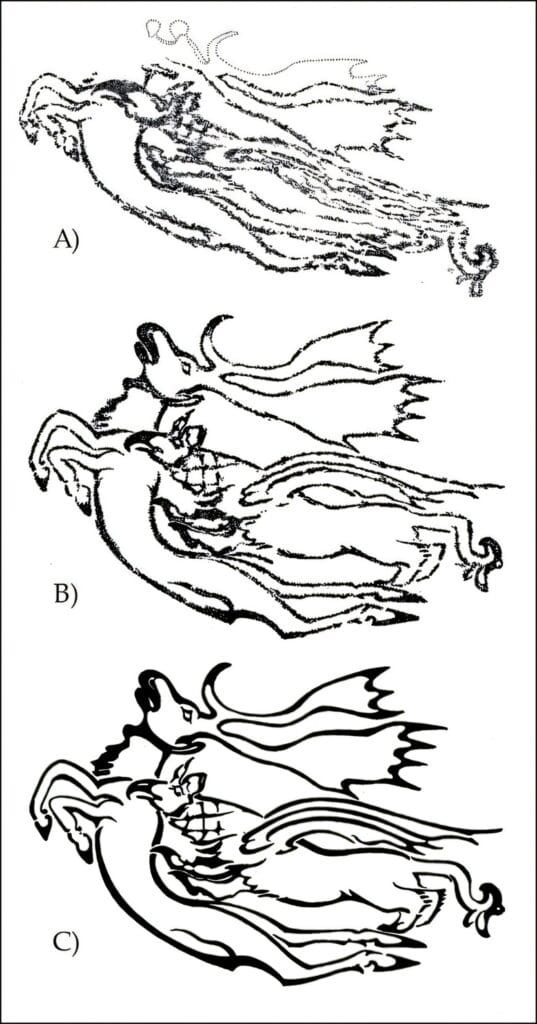

“The tattoos of the Pazyryk culture have always intrigued us due to their elaborate figural designs,” explains Dr. Gino Caspari, lead author of the study and researcher at both the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology and the University of Bern. “But until now, we’ve only had early schematic drawings. We couldn’t see the fine detail—the craftsmanship.”

Most previous interpretations of Pazyryk tattoos centered around symbolism and social meaning, such as tribal affiliation, shamanic power, or spiritual protection. But these studies were based on hand-drawn reconstructions, often lacking the clarity needed to discuss how the tattoos were actually made. What tools were used? What techniques? Was tattooing a common skill, or one reserved for trained specialists?

The new imaging techniques changed all that. The researchers created a three-dimensional, near-infrared scan of the mummy’s forearms, exposing the minute features of the ink under the skin with astonishing clarity. What they found told a new kind of story.

A Tale of Two Arms—and Two Artists

One of the most remarkable findings came from comparing the tattoos on the mummy’s right and left forearms. The tattoos on the right were cleaner, more precise, and technically superior. In contrast, the left arm bore designs that were slightly more irregular—fainter lines, less consistent depth. To the trained eye, it was the difference between a master and an apprentice.

“This wasn’t random,” says Dr. Caspari. “It tells us that either two different tattooers worked on this person—possibly at different times—or the same tattooer was developing their skill. Either way, it implies a learning process, an apprenticeship, much like what we see with professional tattooers today.”

Such nuance may seem small, but in the context of archaeology, it’s groundbreaking. Never before has it been possible to attribute individual craftsmanship to tattooing in the prehistoric world. The researchers were even able to identify distinct tool marks and needle groupings by working in collaboration with modern tattoo artists.

Tattooing as a Prehistoric Profession

For the Pazyryk people, tattooing was not just decoration or ritual—it was a practiced, technical craft. The ink didn’t just appear magically under the skin. Someone made it. Someone held the needle. Someone learned the process, made mistakes, and improved over time. In short, tattooing was a job. A profession. A calling.

“The study offers a new way to recognize personal agency in prehistoric body modification practices,” says Dr. Caspari. “Tattooing emerges not merely as symbolic decoration but as a specialized craft—one that demanded technical skill, aesthetic sensitivity, and formal training or apprenticeship.”

This insight marks a shift in how we view prehistoric people. Rather than faceless members of a collective culture, they become individuals—artists, students, masters, practitioners of body art whose work has survived thousands of years, not on cave walls, but on human skin.

A Connection Across Time

Perhaps most moving is what this study reveals about human continuity. While separated from us by over two thousand years and thousands of kilometers, the ancient tattooers of the Pazyryk culture were not so different from the professionals you’d find in any tattoo parlor today. They practiced. They improved. They left behind work they were proud of—or perhaps wished they’d done better.

“This made me feel like we were much closer to seeing the people behind the art,” Dr. Caspari reflects. “How they worked and learned and made mistakes. The images came alive.”

It’s one thing to discover an ancient civilization; it’s quite another to see the hand of an individual who once lived, breathed, and made choices. Through these tattoos, we witness not just cultural heritage but personal expression, technical learning, and a human desire to mark the body with meaning and beauty.

Preserving More Than Skin

The implications of this study extend beyond archaeology. As climate change threatens the permafrost of Siberia, many of these ancient remains are at risk of thawing and decaying. The detailed digital scans used in this project offer a way to preserve knowledge even if the physical artifacts are lost.

What’s more, the techniques developed here could be applied to other ancient mummies with tattoos—from Egypt to South America—opening new doors in the study of prehistoric body modification, art, and identity.

By marrying modern technology with ancient skin, researchers have bridged the gap between science and story, between anthropology and artistry. They’ve given voice to the hands behind the ink.

Ink, Ice, and Immortality

As the ice mummy lies once more in its frozen tomb, its secrets now digitally preserved, we are left with a new vision of prehistory—one that is personal, emotional, and unexpectedly relatable.

The ancient tattooers of Siberia may have lived in a world of wool, bone, and horseback warfare, but their tools and techniques reflect a human impulse still alive today: the desire to mark who we are, to learn by doing, and to create beauty that lasts.

In the language of ink and flesh, they left a message. And, thanks to science, we can now read it—not as a relic of the distant past, but as a mirror of ourselves.

More information: High-resolution near-infrared data reveal Pazyryk tattooing methods, Antiquity (2025). doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10150