In 2013, a Facebook post changed the history of anthropology. The call was unusual: “Short, skinny, and fit anthropologists wanted—must not be claustrophobic.” Behind this lighthearted but serious advertisement was a mission led by paleoanthropologist Lee Berger and his team at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa. They needed a group of small but fearless scientists to explore the Rising Star cave system, a maze of deep chambers, tight passages, and treacherous rock that promised something extraordinary.

What began as an expedition into the unknown turned into one of the most astonishing discoveries in human history: the remains of a new species of ancient human relative, Homo naledi. Buried thirty meters below the surface, within a dark and twisting labyrinth, lay a hidden chamber filled with bones untouched for hundreds of thousands of years.

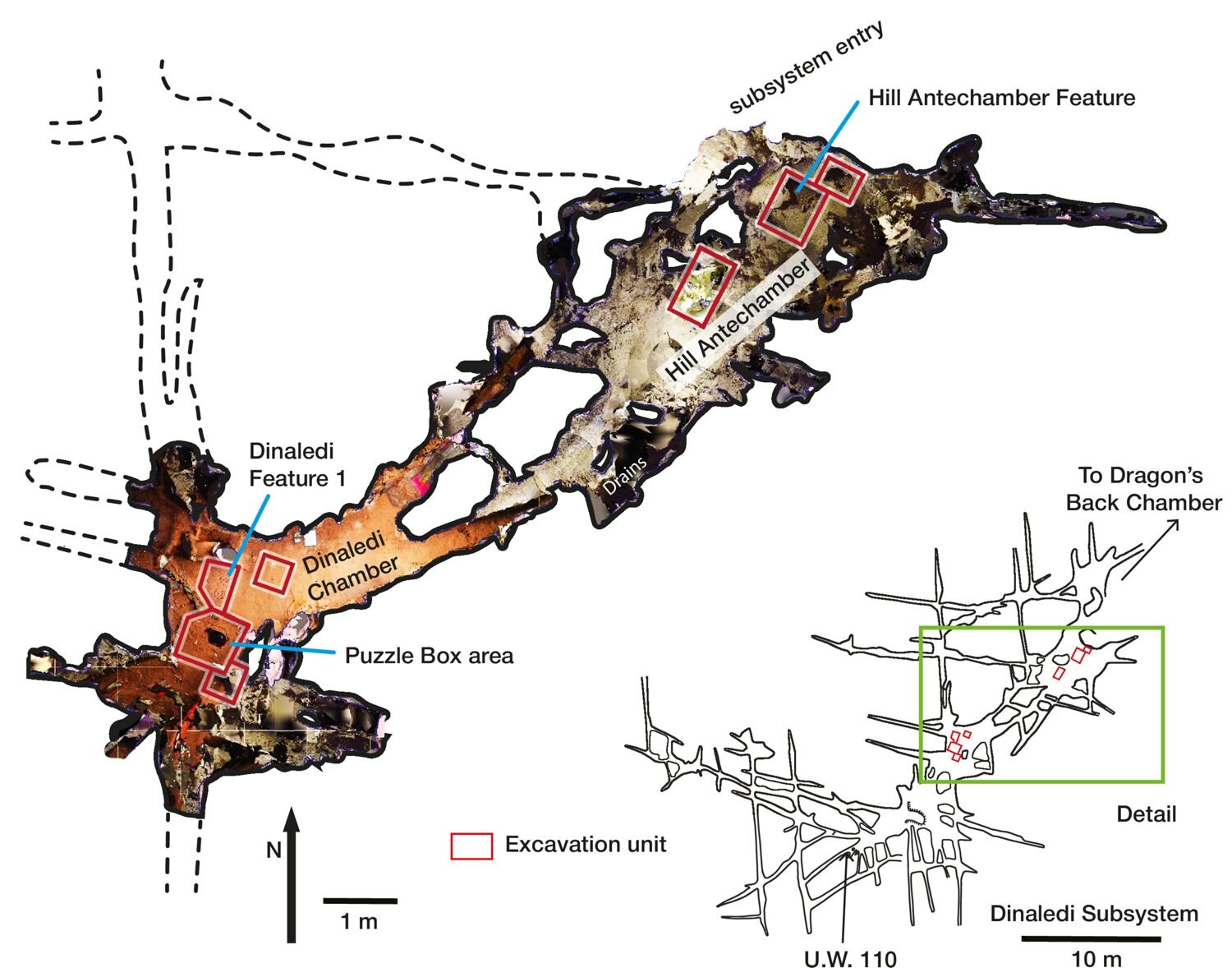

The find did not consist of a handful of fragments or a single skull, as is often the case in paleoanthropology. Instead, more than 1,500 well-preserved fossilized bones were uncovered, belonging to at least 15 individuals. The researchers nicknamed the most concentrated burial area the “Puzzle Box”—an apt description for the enigma that Homo naledi posed.

Who Were the Naledi?

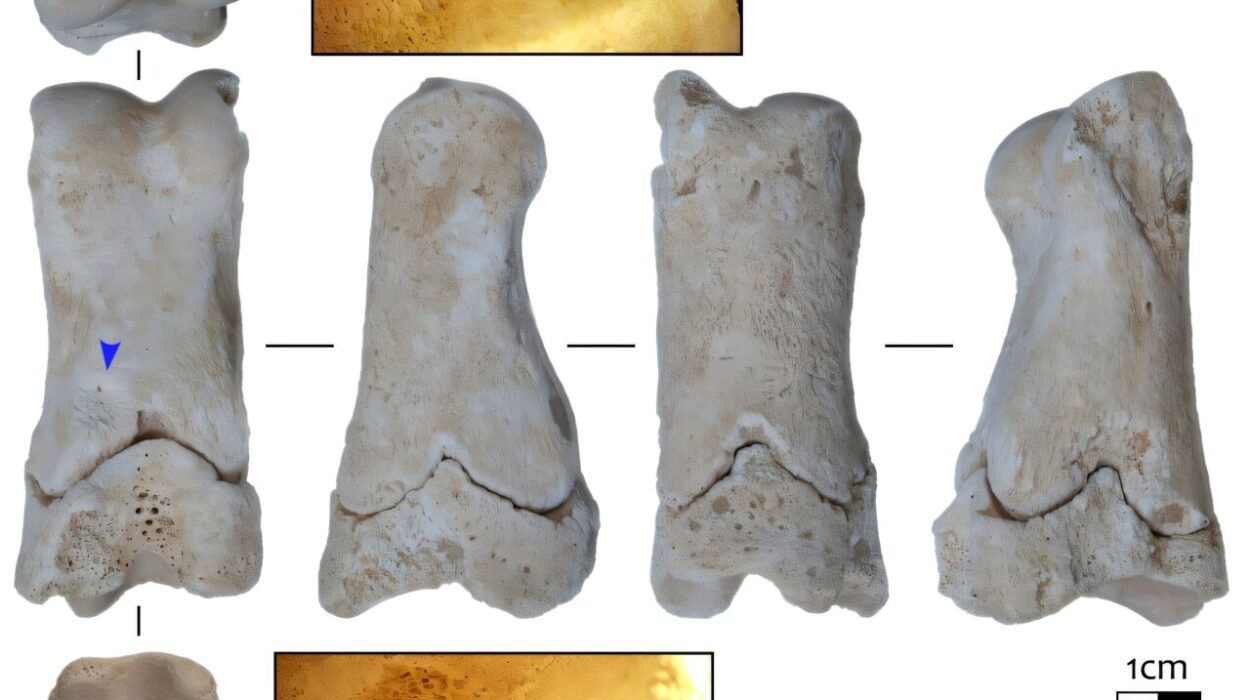

Homo naledi was unlike any hominin species discovered before. Standing under five feet tall, with slender builds and brains scarcely larger than those of a modern human infant, they appeared primitive in many ways. Their hips and shoulders resembled those of much older australopiths, yet their feet and hands were strikingly modern, hinting at a blend of traits that blurred the boundaries of the human family tree.

Dating techniques revealed that these beings lived around 240,000 years ago, during a time when multiple human cousins shared the Earth—among them Neanderthals, Denisovans, and the earliest members of our own species, Homo sapiens. In this diverse evolutionary landscape, Homo naledi stood apart, not simply for their unusual anatomy, but for something even more remarkable: their treatment of the dead.

A Bold Claim: The First Burials

When Berger and his team first announced their findings in 2015, the news reverberated far beyond the scientific community. The sheer number of fossils was astonishing. But even more astonishing was the claim that Homo naledi deliberately buried their dead—a behavior long considered unique to modern humans, and possibly Neanderthals.

The suggestion was controversial. Burial was often thought of as a marker of advanced cognition, even of symbolic thought or spiritual belief. For a small-brained species like Homo naledi, such behavior seemed improbable. Critics questioned the interpretation, pointing out that the announcement had come before extensive peer review and without broad consultation from outside experts.

Yet the evidence has only grown stronger. In 2023, Berger’s team published their most comprehensive study yet, with collaborators from six countries and 28 institutions. Their conclusion: the fossils could not have ended up in the Dinaledi Chamber by accident. The pattern of articulated skeletons, the absence of carnivore marks, the dry cave conditions that ruled out water transport, and the deliberate placement of bodies all pointed to intentional burial.

The Challenge of the Cave

To reach the burial sites, living Homo naledi would have needed extraordinary determination. The Dinaledi Chamber lies deep within the Rising Star system, accessible only by crawling through passages so narrow that even the modern excavators had to be specially chosen for their size. Imagine carrying the lifeless body of a loved one through absolute darkness, guided only by touch, or perhaps the faint flicker of firelight. It was not a task undertaken casually—it required planning, effort, and purpose.

Why would these small-brained hominins take such risks? One explanation is practical: burying bodies in hidden places prevents the smell of decay from attracting predators, or spares the living from disturbing encounters with decomposing remains. But practical necessity does not fully explain the repeated use of the same chamber, generation after generation. Was there sentiment, a sense of belonging, or even a glimmer of symbolic thought behind these acts?

Lessons from the Neanderthals

The debate over burial is not new. For decades, scientists have argued about whether Neanderthals buried their dead. Ralph Solecki’s famous discovery of the Shanidar “flower burial” in Iraq seemed to suggest ritual behavior, until later analysis showed that pollen may have been introduced by burrowing bees. Still, other Neanderthal burials and symbolic artifacts—from cave paintings to complex tools—have revealed capacities once believed unique to Homo sapiens.

The case of Homo naledi pushes this conversation even further back in time. If a species with such a small brain was burying its dead 240,000 years ago, then the roots of this behavior may run far deeper in our evolutionary history than once thought. Burial may not be the sole domain of large-brained hominins, but rather a broader expression of care, memory, or community.

The Evidence from Rising Star

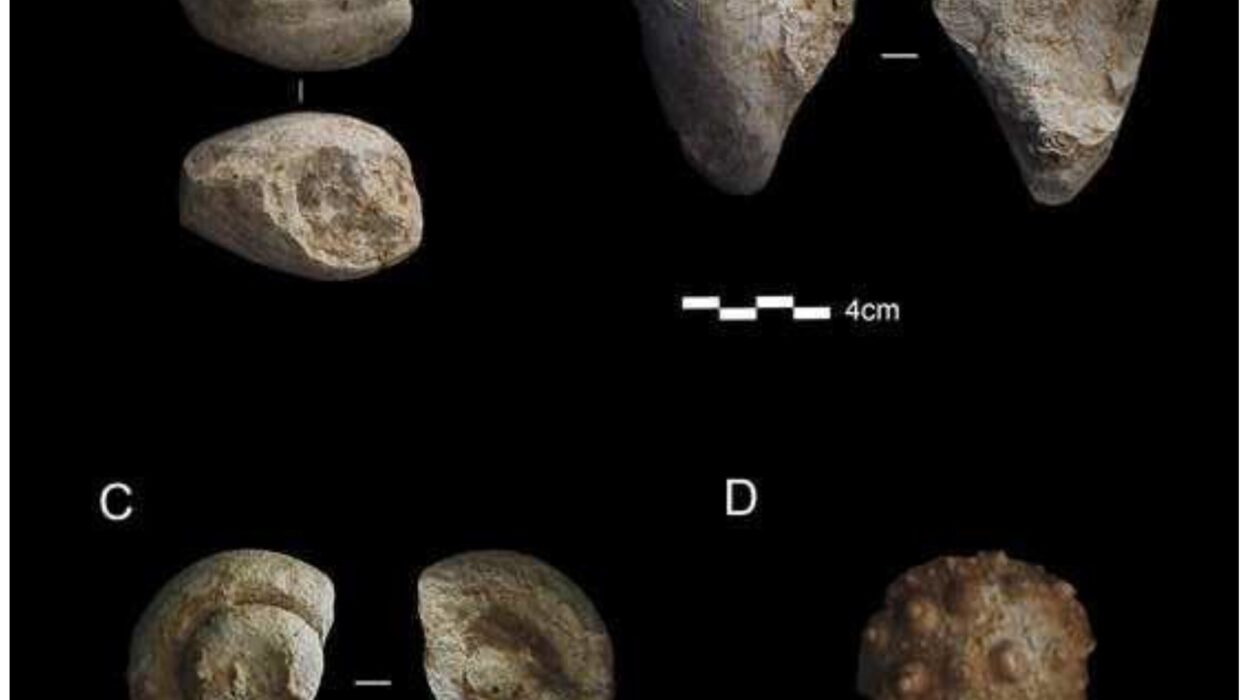

The new study, published in eLife, described nearly 90 skeletal elements and 51 teeth across two new burial areas in the Dinaledi Subsystem. Among them were juveniles, identified by their teeth and skeletal positions. Some remains were remarkably intact: a right foot with its ankle, a partial hand with wrist bones, ribs, jaws, and teeth still aligned as they had been in life.

The condition of the bones and the sediments surrounding them rule out explanations like flooding, rock falls, or random accumulation. Many of the bones appeared disturbed only after initial burial, suggesting repeated visits and secondary placement—possibly as new burials were added over time.

Intriguingly, a single stone object was also found in one burial area, lying in an orientation inconsistent with natural processes. Its significance remains under study, but it adds to the mystery of whether Homo naledi engaged in behaviors that went beyond practicality, edging into symbolism.

What the Burials Mean

The implications of Homo naledi’s burial practices are profound. For decades, the narrative of human evolution has been one of cognitive superiority—our species’ intelligence and symbolic thought distinguished us from all others. Burial, in particular, was seen as a hallmark of modern humanity, perhaps linked to concepts of life, death, and even the afterlife.

But if Homo naledi, with their tiny brains and primitive traits, also buried their dead, then the capacity for such behavior may not have been tied to brain size alone. It suggests that cognition, culture, and compassion may have evolved in unexpected ways, scattered across different branches of the human family tree.

A Window into the Unknown

The Rising Star cave remains the only known home of Homo naledi, and so far, no signs of daily habitation have been found within it. The chamber seems to have been used exclusively as a place for the dead. This is itself extraordinary, hinting at traditions, choices, and practices that have left no other trace.

Perhaps most haunting of all is the thought that Homo naledi survived long enough to overlap with the earliest Homo sapiens. For a time, our species and theirs walked the Earth together. Did we ever meet? Did we recognize one another as kin? Or were they gone before we had the chance to know them?

The Enduring Mystery

The story of Homo naledi is both humbling and inspiring. It reminds us that the human journey is not a straight line of progress, but a branching tree of experiments, adaptations, and unexpected complexities. It teaches us that intelligence and culture cannot be reduced to brain size alone. And it challenges us to rethink what it means to be human.

In the depths of a South African cave, in silence and darkness, a small-bodied species carried their dead into hidden chambers, leaving behind clues that would only be uncovered hundreds of thousands of years later. Their story has only just begun to be told.

Homo naledi may be gone, but in their burials, they whisper something timeless: that even in the earliest days of our lineage, life and death were bound together by memory, meaning, and care.

More information: Lee R Berger et al, Evidence for deliberate burial of the dead by Homo naledi, eLife (2025). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.89106.3