When we imagine the great empires of antiquity, names like Rome, Egypt, or Greece often dominate the imagination. Yet long before Caesar crossed the Rubicon or Alexander dreamed of conquest, there was Persia—a land and a people who built something entirely new. The Persians were not simply rulers of a kingdom; they were architects of the first super-empire, an organized, multicultural, and enduring state that spanned from the Aegean Sea in the west to the Indus Valley in the east.

The story of the Persians is not merely one of conquest and power. It is the story of vision, innovation, and a philosophy of governance that shaped much of the ancient world and influenced future civilizations for centuries. To explore the Persians is to explore the first true experiment in global rule, a system where culture, economy, religion, and politics intertwined on a scale never before attempted.

The Land of Persia: Roots of an Empire

Persia’s heartland lay on the Iranian plateau, a land of rugged mountains, fertile valleys, and sweeping deserts. This geography forged resilience in its people. The Persians were not the first to inhabit this region; they emerged amid ancient civilizations such as the Elamites to the southwest and the powerful Median tribes to the north. By the first millennium BCE, Indo-Iranian peoples—speakers of an early Indo-European language—had migrated into this land, settling and adapting to its challenges.

The Persians were one among many tribes, relatively minor compared to their Median cousins. They lived in the region known as Parsa (modern-day Fars in southern Iran), from which their name was derived. It was from these modest beginnings that they would eventually rise to forge the largest empire the world had yet seen.

Cyrus the Great: Father of the Persian Empire

The story of Persia’s transformation begins with Cyrus II, known to history as Cyrus the Great. Around 550 BCE, Cyrus united the Persian tribes and then turned his attention outward. His genius lay not only in military skill but in vision. Cyrus understood that power was not maintained merely by conquest but by respect for the diversity of peoples within an empire.

First, Cyrus defeated the Medes, integrating their kingdom into his own while preserving much of their structure. He then turned west, toppling the wealthy kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor, and later marched into Mesopotamia, conquering Babylon in 539 BCE. Yet what set Cyrus apart was not just that he conquered Babylon—it was how he did so. Rather than plunder, he presented himself as a liberator. He allowed the exiled Jews to return to Jerusalem, restored temples to their gods, and declared himself chosen by Marduk, Babylon’s patron deity.

The famous Cyrus Cylinder, often called the first charter of human rights, records these policies. While modern interpretations sometimes exaggerate its liberalism, it remains an extraordinary statement of imperial philosophy: rule by tolerance, respect, and inclusion. This was the Persian model, and it would endure long after Cyrus himself fell in battle in 530 BCE.

Cambyses and Darius: Expansion and Organization

Cyrus’s son, Cambyses II, expanded the empire further by conquering Egypt in 525 BCE, bringing the land of the pharaohs under Persian rule. But it was under Darius I, known as Darius the Great (reigned 522–486 BCE), that the Persian Empire truly took shape as the world’s first superpower.

Darius was not only a conqueror—though he extended Persian control into the Indus Valley and attempted to subdue Greece—he was above all an organizer. His reforms transformed Persia from a loose collection of kingdoms into a centralized empire of astonishing efficiency.

He divided the empire into provinces called satrapies, each governed by a satrap (provincial governor). This system balanced local autonomy with imperial oversight, ensuring both stability and loyalty. To prevent rebellion, Darius created a system of royal inspectors, known as the “King’s Eyes and Ears,” who traveled the empire to keep satraps accountable.

Economically, Darius standardized coinage, weights, and measures, facilitating trade across his vast realm. He built the Royal Road, a network of highways that connected cities over 2,500 kilometers, enabling messages and goods to move at unprecedented speed. Couriers could relay a message across the empire in days—a marvel of logistics that foreshadowed modern communications.

Darius also established Persepolis, the ceremonial capital, whose grand terraces and reliefs still inspire awe today. The art of Persepolis reflects Persia’s philosophy of empire: delegations from subject peoples are depicted bringing tribute, not as slaves or victims, but as honored participants in a shared order.

Religion and the Persian Worldview

At the heart of Persian identity was a spiritual framework rooted in Zoroastrianism, a religion attributed to the prophet Zoroaster (or Zarathustra), who lived perhaps around the 2nd millennium BCE. Zoroastrianism taught a dualistic vision of the world: the eternal struggle between Ahura Mazda, the god of light, truth, and order, and Angra Mainyu, the spirit of chaos and destruction.

This cosmic battle was reflected in human life, where individuals were called to choose truth (asha) over the lie (druj). Concepts like free will, judgment after death, and the triumph of good over evil deeply influenced later Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

While Persian kings claimed divine sanction from Ahura Mazda, they rarely imposed Zoroastrianism on their subjects. Instead, they cultivated tolerance, allowing diverse religions to flourish within the empire. This policy not only secured loyalty but also created a mosaic of cultural richness unparalleled in the ancient world.

The Greco-Persian Wars: Clash of Civilizations

No history of Persia can be told without its dramatic encounters with Greece. In 490 BCE, Darius launched the first Persian invasion of Greece, only to be repelled at the Battle of Marathon. His son Xerxes I renewed the campaign a decade later, famously crossing the Hellespont with a vast army and fleet.

The Persians achieved victories, including the burning of Athens, but their advance was halted at battles such as Salamis (480 BCE) and Plataea (479 BCE). Though Persia remained a superpower long after, these wars etched themselves into Western memory as defining moments of resistance against tyranny—an interpretation often colored by Greek propaganda.

In reality, the Persians saw Greece as a minor frontier compared to their dominions in Asia. Yet the wars symbolized the clash between two worldviews: Persia’s centralized, multicultural empire and Greece’s fragmented but fiercely independent city-states.

Art, Architecture, and the Persian Legacy

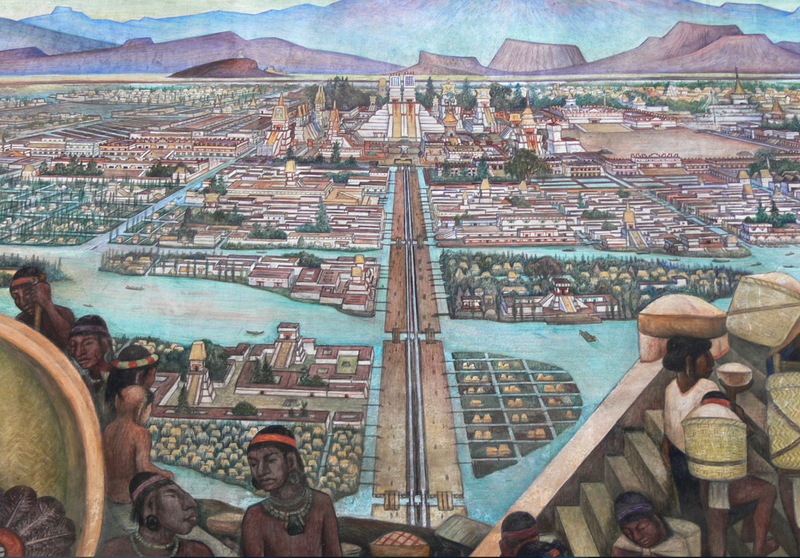

The Persians were not merely conquerors; they were builders of a culture that blended traditions from across their empire. Their architecture reflected grandeur and inclusivity. The palaces of Persepolis, Susa, and Pasargadae combined Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Anatolian influences, resulting in structures that embodied the empire’s diversity.

Reliefs at Persepolis depict dignitaries from across the empire—Medes, Egyptians, Greeks, Indians—bringing tribute in peace. These works communicate a vision of unity under Persian kingship, a world where diversity was celebrated rather than erased.

Persian art extended to luxury goods, from intricate jewelry to textiles, many of which influenced neighboring cultures. Their gardens, carefully designed with flowing water and ordered plantings, introduced the very concept of the “paradise”—a word derived from the Old Persian pairidaeza, meaning walled garden.

Administration, Trade, and Connectivity

What truly distinguished Persia as the first super-empire was its administrative sophistication. Unlike earlier empires that often collapsed under their own weight, Persia thrived because of its ability to integrate peoples and regions.

The satrapy system provided both local autonomy and central authority. Taxes were collected fairly, infrastructure was maintained, and laws were standardized. Trade routes flourished, linking Egypt with India, Anatolia with Central Asia. The Royal Road and other highways became lifelines of commerce, diplomacy, and culture.

Persian coinage, particularly the gold daric, became a standard currency across the empire, further stimulating trade. Merchants, artisans, and travelers moved with relative security, protected by the king’s laws. The empire’s stability allowed ideas and technologies to flow freely, making Persia a crucible of cultural exchange.

The Fall of the Achaemenids

No empire is eternal. By the 4th century BCE, internal strife and growing complacency weakened the Persian state. When Alexander of Macedon launched his campaign in 334 BCE, he found an empire still vast but vulnerable.

Within a decade, Alexander had defeated the Persian armies, captured Persepolis, and brought the Achaemenid dynasty to an end. Yet even in conquest, the Persian model endured. Alexander adopted Persian customs, married a Persian princess, and sought to integrate Greeks and Persians into a single realm. In this sense, the Persian vision outlived the empire itself, shaping the Hellenistic world that followed.

Successors and Continuity

Though the Achaemenids fell, Persia was far from finished. Successive dynasties—the Parthians, Sassanians, and later Islamic caliphates—carried forward elements of Persian governance, culture, and religion. The Sassanians, in particular, revived Zoroastrianism as a state faith and rivaled Rome for centuries.

Persian traditions influenced Islamic administration, art, and literature after the Arab conquest. Even today, Iran retains a cultural continuity that stretches back to its ancient roots, a testament to the resilience of its identity.

The Persian Legacy in World History

What makes the Persians unique is not simply that they ruled a vast empire, but that they pioneered principles of governance and tolerance that resonated far beyond their time. Their innovations in administration, infrastructure, and cultural integration became models for later empires, from Rome to the Ottomans.

The idea that diversity could be managed not through suppression but through respect was revolutionary. Their religious philosophy shaped global faiths. Their art and architecture inspired generations. Their political vision demonstrated that empire could be more than domination—it could be a system of order and cooperation.

Conclusion: The Builders of the First Super-Empire

The Persians were the world’s first great imperial experiment, architects of a system that balanced power with tolerance, central authority with local autonomy, and diversity with unity. They created the first true super-empire, a realm that stretched across continents, languages, and cultures, leaving behind not just monuments of stone but ideals that echo through history.

To study the Persians is to encounter not only kings and conquests but a philosophy of rule that sought to bind humanity together under a shared vision. Their empire may have fallen to time, but their legacy remains alive—in the gardens we still call paradise, in the faiths shaped by their ideas, and in the enduring dream that humanity can coexist in diversity.

The Persians remind us that empire is not only about power but about possibility—the possibility of building something vast, complex, and humane. In that sense, they were not just rulers of the ancient world; they were pioneers of civilization itself.