Roughly 10,000 years ago, something extraordinary began to unfold. Across the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East—stretching through modern-day Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and surrounding regions—small groups of humans were experimenting with something radically different from the way their ancestors had lived for hundreds of thousands of years. Instead of following seasonal herds or gathering wild plants, they began to cultivate crops, domesticate animals, and establish permanent villages.

This shift—from nomadic hunting and gathering to farming and settled life—was one of the most profound transformations in the story of our species. Historians and archaeologists call it the Neolithic Revolution, and it laid the foundations for everything we recognize as civilization: cities, writing, social hierarchies, and eventually, modern nations.

But one question has puzzled researchers for decades: How exactly did farming spread? Was it primarily carried by migrating communities of farmers who moved into new territories, bringing their way of life with them? Or did local hunter-gatherers adopt farming practices through contact and exchange, gradually changing their lifestyles without large-scale migration?

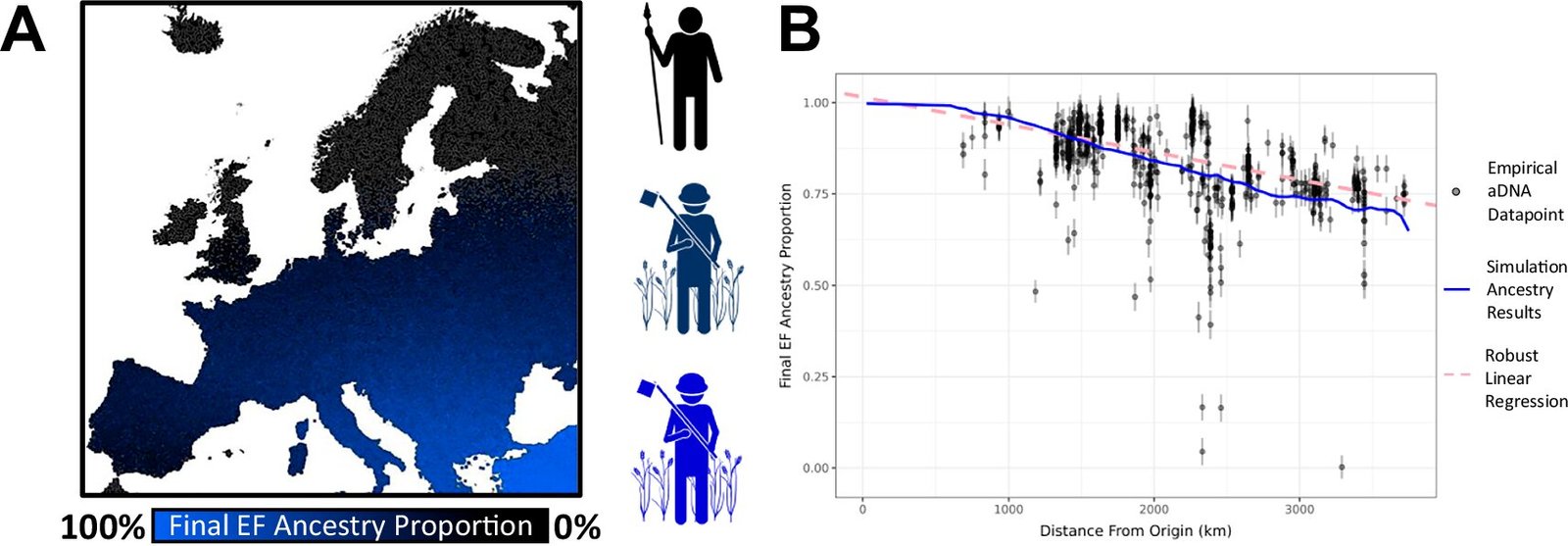

A groundbreaking study led by researchers at Penn State University has now brought clarity to this age-old debate. By combining cutting-edge tools—mathematical models, ancient DNA analysis, and archaeological evidence—the team has shown that the expansion of farming across Europe was driven overwhelmingly by migration.

Beyond a Simple Story

The story of how agriculture spread is not a trivial historical detail; it is central to understanding human identity. Farming did not just feed larger populations. It reshaped social structures, altered human biology, and transformed landscapes forever. Yet, for a long time, scientists struggled to untangle the roles of human movement and cultural adoption in this monumental change.

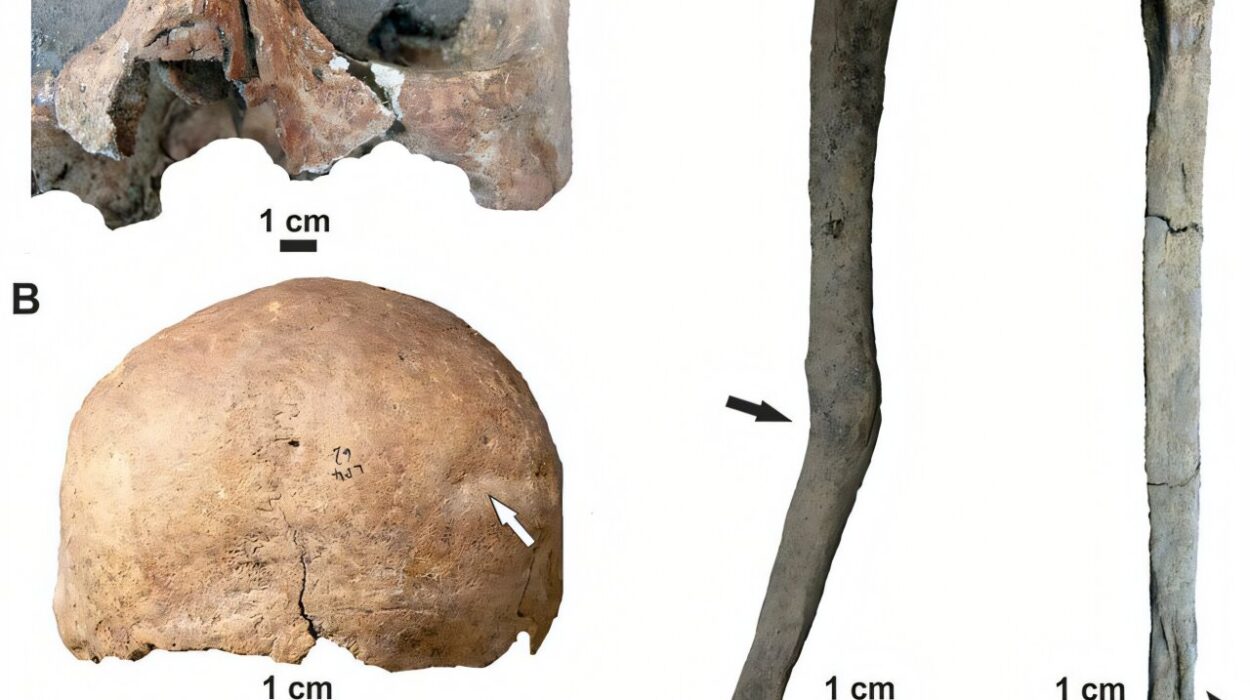

Artifacts, bones, and tools told one part of the story. They showed where early domesticated plants and animals appeared, and how material culture shifted over time. But these clues alone could not reveal whether locals were innovating or outsiders were arriving. Then came the revolution in ancient DNA research—a scientific breakthrough that allows us to extract genetic information from human remains thousands of years old. Suddenly, we could trace ancestry, detect population shifts, and identify biological signatures of migration.

Still, even DNA alone could not provide the whole picture. That is where mathematical modeling and computer simulations came in. By combining archaeological timelines, DNA evidence, and models of population growth, the Penn State team created a comprehensive framework to test the competing hypotheses.

Migration as the Driving Force

The results were striking. The team’s models showed that migration was the dominant factor in spreading agriculture across Europe. Farming did not primarily spread because hunter-gatherers decided to plant crops or herd animals; it spread because farmers themselves physically moved into new lands, carrying their technologies, lifestyles, and genes with them.

Christian Huber, assistant professor of biology at Penn State and senior author of the study, emphasized the complementary insights offered by archaeology and genetics. Artifacts reveal whether individuals relied on farming or foraging, while DNA uncovers where their ancestors came from. When combined, these data sets paint a compelling picture: the spread of farming left a deep imprint on the ancestry of Europeans today, evidence that migration was not just present but essential.

Lead author Troy LaPolice, a doctoral student at Penn State, noted the surprising nature of these findings: “When cultures spread through migration, it is not guaranteed local ancestry patterns will change. But the spread of farming managed to leave a strong and lasting impact on European ancestry.”

The Minimal Role of Cultural Adoption

One of the most fascinating outcomes of the research was the quantification of cultural adoption—or what the researchers called the “cultural effect.” According to their models, the contribution of hunter-gatherers adopting farming practices was vanishingly small—about 0.5%.

In other words, while foragers may have occasionally experimented with farming, they did not adopt it widely enough to drive the spread. The overwhelming dynamic was displacement: farming populations expanded, and foraging populations dwindled, coexisted uneasily, or were absorbed at very low rates.

The assimilation rate, as measured by the team, was extraordinarily low. Only about one in 1,000 farmers converted a hunter-gatherer to farming each year. Even mating between groups was rare. Farmers largely married farmers, and hunter-gatherers largely married hunter-gatherers, with less than 3% of pairings occurring between the two groups.

This suggests that, far from a seamless cultural exchange, the spread of farming involved the migration of relatively closed communities whose way of life gradually dominated.

Echoes in Our DNA

Even at such low assimilation rates, the legacy of those rare contacts persists today. When hunter-gatherers were integrated into farming communities, they introduced useful genetic traits—some of which survive in modern Europeans. These genetic echoes remind us that even small moments of interaction in the deep past can ripple across millennia.

This finding also highlights a fascinating paradox. Cultural adoption may have been minimal, but genetic contributions from foragers remain detectable. The story of the Neolithic Revolution, then, is not one of total replacement but of a subtle blending in which farming prevailed as a lifestyle, yet hunter-gatherer ancestry never fully disappeared.

The Human Side of the Transition

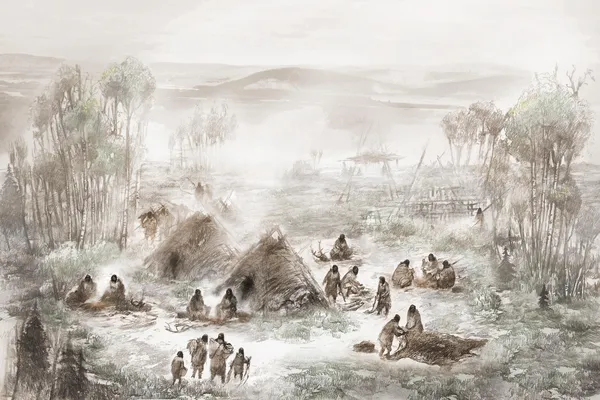

It is easy to discuss the Neolithic Revolution in abstract terms—migration rates, percentages, simulations. But at its core, this was a deeply human story. Imagine the meeting of two worlds: a band of hunter-gatherers who knew the rhythms of the forest, the migrations of animals, the secrets of wild plants, encountering farmers who brought seeds, animals, and new tools.

The hunter-gatherers may have seen farming as risky or unnecessary. After all, why trade the freedom of mobility for the backbreaking labor of tilling soil? To them, the farmers might have seemed strange, tied to a fixed plot of land, dependent on uncertain harvests. To the farmers, foragers may have seemed wild, untamed, and even threatening. These encounters were not merely economic but cultural, social, and perhaps even spiritual clashes.

What the Penn State study shows is that these encounters were not enough to convert large numbers of foragers into farmers. Instead, farming populations grew, moved, and established new settlements, slowly but decisively altering the demographic landscape of Europe.

A New Kind of Historical Reconstruction

What makes this research especially remarkable is the way it reconstructs a time before writing, before oral history, and before direct memory. We have no myths or chronicles from the people who lived through the Neolithic Revolution. All we have are their bones, tools, and the traces of their DNA.

Yet through interdisciplinary science, we can now piece together their story with unprecedented clarity. Computer simulations, genetic sequencing, and archaeological evidence converge to create a new kind of time machine, one that allows us to test hypotheses about how people lived, moved, and interacted thousands of years ago.

LaPolice described the thrill of this approach: “It’s really interesting to be able to understand a time period before any written or oral history. This intense interdisciplinary project allowed us to undertake a new kind of historical reconstruction.”

Rethinking Prehistoric Change

The implications of this study extend beyond the spread of farming. If migration was so dominant in this transformation, what about other major shifts in human history? The spread of metallurgy, the rise of pastoralism, the development of languages—might these too have been driven more by movement of people than by simple cultural diffusion?

Matthew Williams, co-author of the paper, believes this is just the beginning. “This research highlights the power of combining genetic data with archaeological models to uncover the complex behavioral mechanisms of our past,” he explained. “Looking forward, I see this paving the way for a re-evaluation of other major prehistoric cultural shifts.”

Indeed, the methodology pioneered here—blending DNA, archaeology, and modeling—could rewrite much of what we thought we knew about how ideas, technologies, and lifestyles spread.

Lessons for Today

Though separated from us by ten millennia, the Neolithic Revolution holds lessons that resonate today. Migration remains a powerful force in shaping societies, often more influential than the spread of ideas alone. Just as ancient farmers carried their way of life across continents, modern migrations continue to reshape cultures, economies, and identities.

Moreover, the study reminds us that cultural shifts are rarely simple stories of adoption. They are often complex negotiations between groups, marked by both resistance and integration. The fact that foragers contributed little to the farming transition, yet left a lasting genetic legacy, underscores the subtle interplay between culture and biology.

The Endless Human Story

The Neolithic Revolution was not a sudden event but a slow, uneven process that unfolded over centuries. Yet it was decisive, setting humanity on a new path. The Penn State study shows us that this path was carved not mainly by ideas passing from one group to another, but by people themselves—farmers who carried their seeds, animals, and knowledge across vast landscapes, reshaping the world as they went.

Today, when we eat bread, drink milk, or harvest crops, we are heirs to this revolution. And thanks to modern science, we are beginning to understand not just what happened, but how. The story of farming’s spread is the story of human movement, resilience, and transformation. It is a story that continues to shape who we are.

More information: Troy M. LaPolice et al, Modeling the European Neolithic expansion suggests predominant within-group mating and limited cultural transmission, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63172-0