For centuries, historians and scientists alike have been haunted by a question that seemed impossible to answer: What exactly caused the Plague of Justinian, the world’s first recorded pandemic? Described in chilling detail in the writings of Byzantine chroniclers, the disease swept across the Eastern Roman Empire beginning in AD 541, killing tens of millions and reshaping the very structure of Mediterranean society. Yet until recently, these vivid accounts remained circumstantial, lacking the biological evidence needed to identify the culprit.

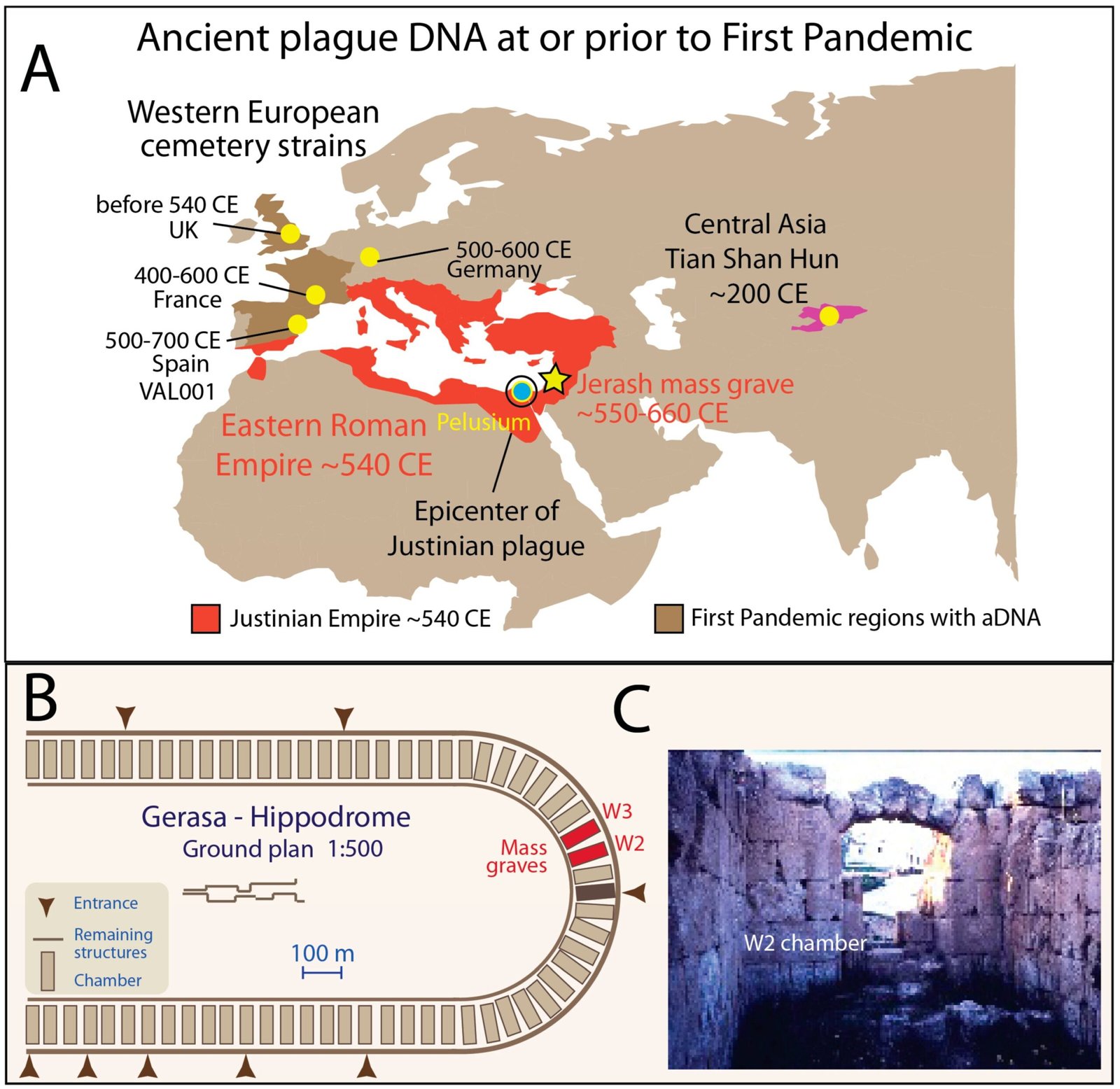

Now, nearly fifteen hundred years later, science has provided the missing link. In a groundbreaking discovery, researchers from the University of South Florida (USF), Florida Atlantic University (FAU), and international partners have uncovered direct genomic evidence of Yersinia pestis—the bacterium responsible for plague—in a mass grave at Jerash, Jordan, just a short distance from the pandemic’s epicenter. For the first time, the microbe long suspected of sparking the Justinian Plague has been definitively tied to the outbreak, resolving one of the great mysteries of human history.

From Historical Accounts to Scientific Proof

The Justinian Plague takes its name from the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, who ruled during its early years. Chroniclers described cities overwhelmed by sudden mortality, corpses filling the streets, and even the great capital of Constantinople brought to its knees. Historians long suspected that Y. pestis—the same pathogen behind the later Black Death—was to blame. Yet until now, no physical traces of the bacterium had been found within the empire itself.

Earlier studies had recovered fragments of Y. pestis DNA in small European settlements far from the heart of the empire, but such findings raised as many questions as they answered. Was plague truly responsible for the devastation described in Byzantine sources, or had historians conflated different diseases under one terrifying name? Without biological evidence from the Mediterranean core, the debate remained unresolved.

That uncertainty has now ended. Using advanced techniques in ancient DNA recovery, the USF-led team sequenced genetic material from eight human teeth excavated from burial chambers beneath Jerash’s former Roman hippodrome. The arena, once a stage for spectacles and civic pride, had been transformed into a mass grave during the sixth and seventh centuries. Genomic analysis revealed unmistakable traces of Y. pestis, genetically uniform across the samples. This uniformity indicates a single, catastrophic outbreak—exactly as historical records had described.

A Glimpse Into an Ancient Catastrophe

The discovery does more than prove the presence of plague; it also illuminates how societies responded to disaster. Jerash was a thriving city of the Eastern Roman Empire, a hub of trade and culture adorned with temples, theaters, and colonnaded streets. That its hippodrome became a mass burial site testifies to the scale of the crisis. Entire urban infrastructures collapsed under the weight of sudden mortality, forcing the living to repurpose public spaces for the grim task of disposal.

By studying the genetic uniformity of the Y. pestis strains, scientists confirmed that the outbreak in Jerash spread with terrifying speed. Unlike modern pandemics that evolve gradually through waves of variants, the Justinian strain seems to have erupted as a rapid and devastating epidemic. This alignment between genetic evidence and historical narrative strengthens the case that plague was indeed the silent architect of one of antiquity’s darkest chapters.

A Broader Evolutionary Story

The Jerash findings, published in the journal Genes, are complemented by a companion study in Pathogens. Together, they place the discovery into a wider evolutionary context. By comparing the Jerash genomes with hundreds of ancient and modern Y. pestis strains, researchers revealed that plague is not a one-time historical anomaly but a recurring phenomenon.

Unlike COVID-19, which arose from a single spillover event and spread globally through sustained human-to-human transmission, plague has emerged again and again from natural reservoirs in rodents and other animals. Each pandemic, from the Justinian outbreak to the Black Death and beyond, represents a fresh eruption of a deeply rooted ecological cycle. In this sense, plague is not merely an ancient disease but an enduring feature of human history, reappearing wherever ecological conditions and human society intersect.

Lessons for the Present

The discovery at Jerash carries profound relevance for today. While plague no longer devastates populations on the scale of past pandemics, Y. pestis is not gone. It persists quietly in animal reservoirs across the globe. Sporadic cases continue to appear each year, including recent fatalities in Arizona and infections in California. These reminders underscore a sobering truth: some pathogens never disappear. They linger, waiting for opportunities to reemerge when ecological and social conditions align.

This reality makes the Justinian evidence more than an archaeological curiosity. It is a warning that pandemics are not singular catastrophes but repeating biological events. They are shaped by human density, trade networks, environmental shifts, and our interconnected world—a lesson made starkly familiar by the COVID-19 pandemic. The parallels between ancient and modern outbreaks remind us that human history is deeply entangled with microbial evolution.

Science Giving Voice to the Past

The researchers themselves emphasize the profound human dimension of their work. To recover DNA from individuals who lived, suffered, and died fifteen centuries ago is not merely a technical feat—it is an act of remembrance. By piecing together their microbial stories, modern science restores their voices to history. What was once silent decay has become a source of knowledge, bridging the gulf between ancient experience and modern understanding.

Greg O’Corry-Crowe, one of the study’s co-authors, reflected on this poignantly: studying the remains of plague victims at a time when the world was gripped by COVID-19 was both scientifically urgent and deeply personal. The parallels between past and present pandemics fostered a sense of connection across time, highlighting our shared vulnerability and resilience.

A Future of Deeper Insights

The Jerash discovery is only the beginning. The research team is now expanding their studies to other historic plague sites, including Venice’s Lazaretto Vecchio, an island that once served as a quarantine zone during the Black Death. With more than 1,200 samples from plague burials, scientists hope to trace how Y. pestis evolved over centuries and how early public health measures shaped both urban resilience and pathogen adaptation.

These efforts promise to shed light not only on the past but also on the present. By understanding how pandemics emerged and spread in antiquity, we may gain insights into how to manage those of the future. The past, preserved in the genomes of ancient pathogens, becomes a guide for navigating the uncertainties of modern global health.

The Enduring Relevance of the Justinian Plague

In finally confirming the microbial culprit of the Plague of Justinian, science has resolved a historical debate stretching back generations. But the discovery is more than a solution to an academic mystery. It is a reminder that pandemics are woven into the fabric of human existence. They are not aberrations but recurring companions, shaped by the same patterns of trade, travel, and environment that continue to define our world today.

The bones at Jerash, the DNA hidden in their teeth, and the genomic signatures of Y. pestis tell a story of loss and resilience. They remind us that while civilizations rise and fall, and pathogens evolve and recur, the quest for understanding endures. Through the lens of modern science, the voices of the long dead return—not only to tell us what they suffered, but to warn us of what may yet come.

More information: Swamy R. Adapa et al, Genetic Evidence of Yersinia pestis from the First Pandemic, Genes (2025). DOI: 10.3390/genes16080926

Subhajeet Dutta et al, Ancient Origins and Global Diversity of Plague: Genomic Evidence for Deep Eurasian Reservoirs and Recurrent Emergence, Pathogens (2025). DOI: 10.3390/pathogens14080797