The Neolithic period, often celebrated as the dawn of agriculture and permanent settlements, carries with it a reputation for progress and transformation. It was during this era that humans shifted from roaming hunter-gatherers to farmers who cultivated the land, built villages, and laid the groundwork for complex societies. Yet beneath this story of innovation lies another narrative—one of violence, fear, and conflict.

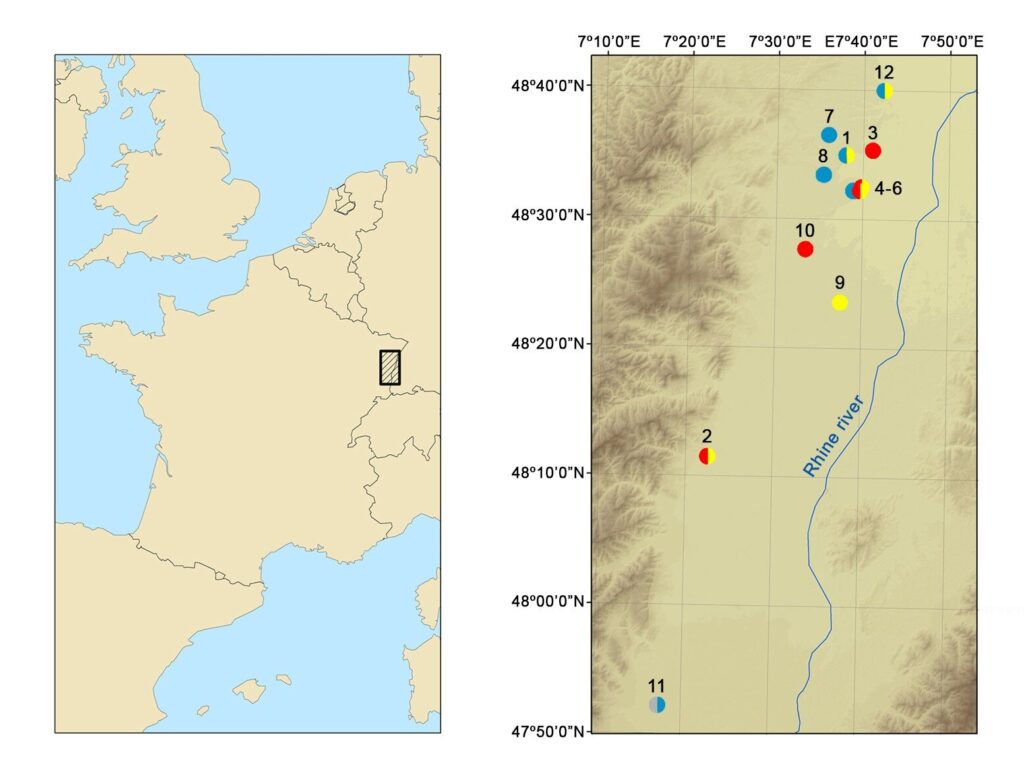

For many communities in Neolithic Europe, life may have been far more brutal than the idyllic images of peaceful farming villages suggest. Archaeological discoveries in Northeastern France, particularly at Achenheim and Bergheim, have revealed a grim reality: massacres, abductions, executions, and mass graves dating back to around 4300–4150 BCE. These findings suggest that violence was not only present but deeply woven into the fabric of Neolithic society.

Burial Pits and Grim Discoveries

In 2015, archaeologists uncovered large burial pits filled with the remains of men, women, and children. The condition of the bodies told a haunting story. Many had been mutilated—arms severed, limbs broken, and wounds inflicted that went far beyond what was necessary to kill. These individuals were not simply buried after death; they were brutalized, possibly as part of ritualized violence or acts of terror.

The purpose of such treatment was unclear at first. Were these people prisoners of war? Outcasts from their own community? Sacrificial victims? Or perhaps fallen enemies brought back from the battlefield as symbols of triumph?

At the same sites, however, other pits contained individuals buried more peacefully, their bodies intact and seemingly treated with care. These graves likely belonged to members of the local community, hinting at a stark divide between insiders and outsiders.

Tracing Lives Through Bones and Teeth

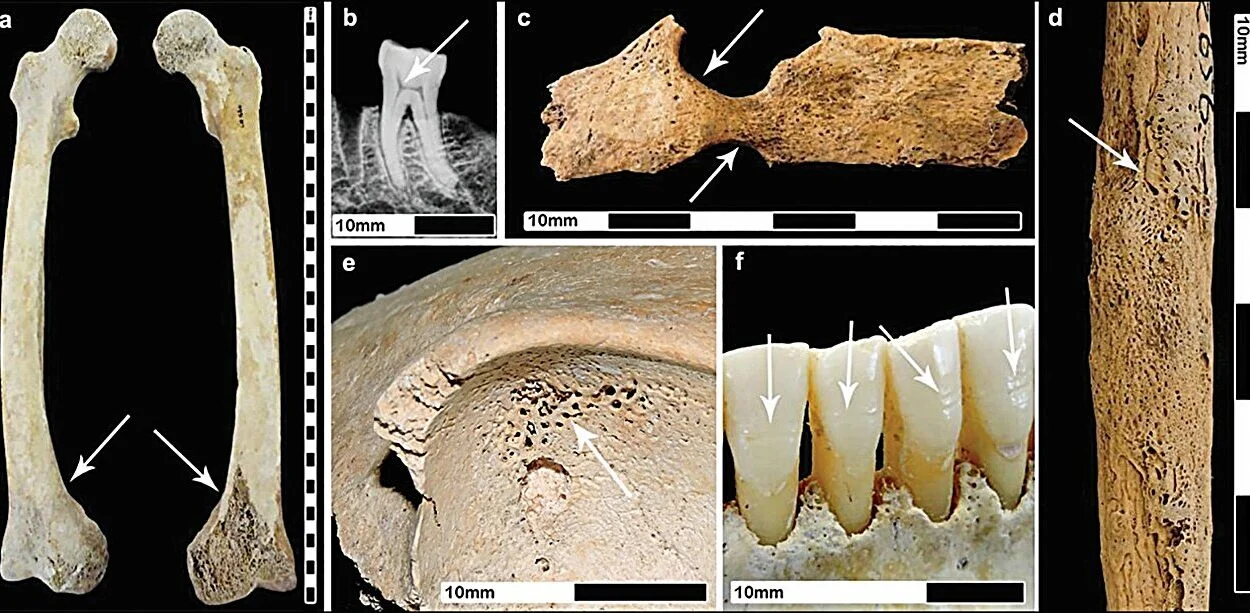

To go beyond speculation, a team of researchers turned to science that reaches deep into the past: isotopic analysis. By examining chemical traces preserved in the teeth and bones of 82 individuals from the burial pits, scientists could reconstruct aspects of their lives. Teeth, formed in childhood, reveal information about diet and mobility in early years, while bones reflect more recent living conditions.

The results were striking. Those who had been mutilated and discarded bore isotopic signatures that set them apart from the locals. Their diets were different, hinting at cultural practices foreign to the community that buried them. Their childhood mobility patterns suggested migration—indicating they were not native to the region.

In contrast, the individuals buried without violence showed isotopic patterns consistent with local life. This divide strongly suggests that the tortured victims were outsiders—very likely captured enemies.

Violence as a Social Practice

The research paints a picture of Neolithic communities where violence was not random but organized, socially recognized, and perhaps even celebrated. Severed arms found among the remains may have served as trophies of victory, displayed as proof of dominance over rivals.

The researchers note that while heads and hands are the most commonly documented human trophies in archaeological records, other body parts were also prized in various cultures throughout history. In this case, upper limbs may have held symbolic value, perhaps representing the strength of enemies literally stripped away.

These practices may represent one of the earliest well-documented examples of martial celebrations in prehistoric Europe. Violence was not just an unfortunate byproduct of survival but a deliberate and ritualized act that reinforced community identity and power.

Belief, Fear, and the Dehumanization of the Enemy

Why did Neolithic communities engage in such brutality? The answer may lie in a combination of spiritual belief, political necessity, and psychological manipulation.

The researchers suggest that victims could have been offered as sacrifices, their suffering believed to provide food or favor for ancestors or gods. The spectacle of merciless brutality may also have legitimized political authority, demonstrating a leader’s ability to protect and dominate.

At the heart of this system was the dehumanization of outsiders. Enemies were not seen as fellow humans but as dangerous, corrupt forces deserving of cruelty. By portraying opponents as evil or depraved, communities could justify killing and mutilating them without guilt. This psychological distancing—what scholars call “othering”—allowed violence to become normalized, even celebrated.

Such patterns are not unique to the Neolithic period. They echo throughout history, from ancient empires to modern wars. The fear of what happens if a demonized enemy is not destroyed often drives societies to escalate violence, convincing themselves it is a moral necessity.

A Window Into Prehistoric Human Nature

The discoveries at Achenheim and Bergheim force us to rethink our image of Neolithic Europe. Far from a peaceful farming utopia, it was a world where violence, ritual, and belief intertwined. These communities cultivated crops and raised livestock, but they also waged wars, took captives, and mutilated bodies in acts of symbolic dominance.

This duality reflects something deeply human: our capacity for creation and destruction, compassion and cruelty. The Neolithic period gave rise to many of the social structures we recognize today, but it also reveals how power and fear can drive people to extremes.

Lessons From the Distant Past

What makes this research powerful is not only what it tells us about prehistory but what it reflects about ourselves. The dehumanization of enemies, the use of brutality as a political tool, and the intertwining of violence with ritual belief are patterns that echo across time.

Understanding these ancient practices is not merely about studying the past—it is about recognizing continuities in human behavior. The story of Neolithic France reminds us that progress and violence often coexist, and that the ways we define “us” and “them” shape the course of history.

In the burial pits of Bergheim and Achenheim, we find not only bones and broken limbs but a mirror held up to humanity—a reminder that the struggle between cooperation and conflict, empathy and cruelty, has been with us since the very beginnings of settled life.

More information: Teresa Fernández-Crespo et al, Multi-isotope biographies and identities of victims of martial victory celebrations in Neolithic Europe, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv3162