At first glance, the desert east of Aswan looks barren—an endless sweep of sand and rock beneath the burning Egyptian sun. Yet, hidden on the cliff faces and scattered across the stone, there are hundreds of images carved more than five millennia ago. These rock inscriptions, faint but enduring, tell a story of power, belief, and the origins of kingship itself. They reveal how, on the edge of the Nile Valley, new ideas about sovereignty began to take shape—ideas that would ultimately give rise to the pharaohs of ancient Egypt.

Among the most striking names to emerge from this prehistoric tableau is that of a mysterious ruler: Scorpion. His legacy, etched in stone, is part history, part myth, and part symbol. The inscriptions do not give us a complete biography, but they whisper fragments of a moment in time when the Egyptian state was still in its infancy, and rulers were fashioning the very concept of kingship.

The First Territorial State

Over 5,000 years ago, Egypt was undergoing a transformation. Small chiefdoms and local communities were coalescing into something entirely new—the world’s first territorial state. Stretching some 800 kilometers along the Nile, this early Egypt was more than a collection of villages; it was a centralized power that claimed dominion over an entire land.

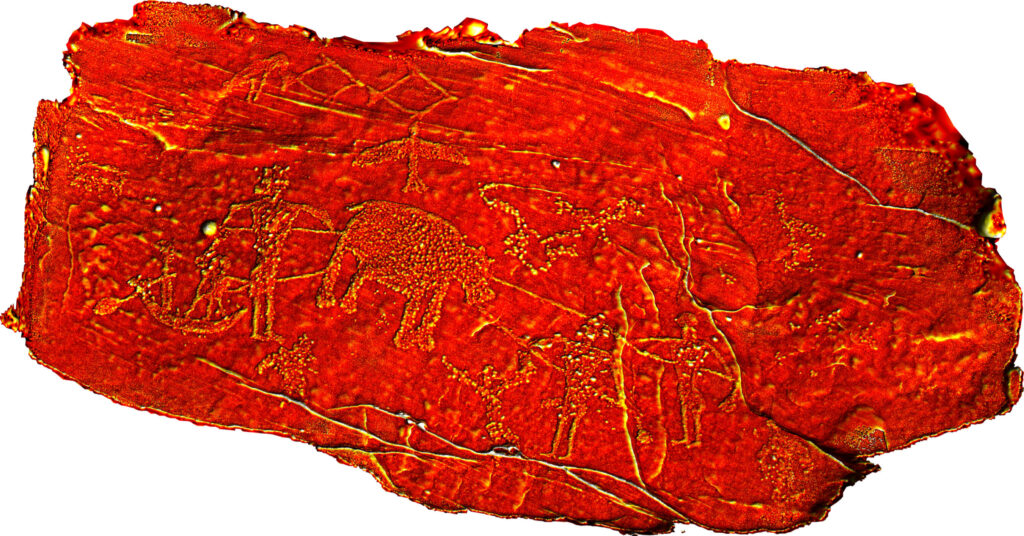

The evidence from Wadi el Malik and nearby wadis shows how this transformation was represented in art. The rock carvings, studied by Prof. Dr. Ludwig Morenz of the University of Bonn and his colleague Mohamed Abdelhay Abu Bakr, depict rulers not only as human leaders but as beings with divine authority. This was more than political propaganda—it was an attempt to invent kingship as a sacred institution.

The Name of Scorpion

One of the most tantalizing inscriptions from the desert carries the phrase: Domain of the Horus King Scorpion. Here, the king’s name appears alongside hieroglyphs that may represent the earliest known place name in the world. The scorpion, a dangerous and feared animal, was an emblem of power—an embodiment of the authority and danger a ruler could command.

We know little about Scorpion the man, but the imagery surrounding his name suggests that he was part of a lineage of rulers who used animals as symbols of dominion. Before him, there was a king identified with the bull—an image of brute strength. Before that, rulers bore names tied to dangerous creatures like the venomous centipede. Each of these names was not only a personal identifier but a metaphor, linking human leadership to the fierce forces of nature.

Kingship in Images

The desert carvings form what scholars call a “royal rock art tableau.” Here, rulers are depicted in scenes of conquest and dominance. Scorpion and his predecessors are shown larger than life, their enemies reduced to tiny, subjugated figures. Some carvings depict rulers trampling foes, their heads severed in a brutal testament to victory. These images were not mere boasts—they were political statements carved into the living stone, meant to endure long after the battles themselves were forgotten.

Alongside the violence, there are also symbols of religion. One striking carving shows a great boat hauled by 25 men. This was no simple river vessel—it was the “boat of the gods,” a symbol of sacred processions that connected different regions of Egypt, from the fertile Nile Valley to the barren wadis of the desert. In this way, kingship was linked not only to military strength but also to divine order and cosmic harmony.

Gods of the Early Kings

Rulers like Scorpion did not present themselves simply as gods. Instead, they portrayed themselves as earthly representatives of divine power. In Scorpion’s time, the chief deities were Bat, a celestial cow goddess associated with fertility, and Min, a male deity linked to hunting and the desert periphery. Together, Bat and Min symbolized the balance between fertile farmland and the wild lands beyond. By aligning themselves with these gods, rulers positioned themselves as mediators between order and chaos, civilization and wilderness.

This process has been called “pharaoh-fashioning”—the crafting of kingship through symbols, images, and divine associations. At a time when centralized rule was still novel, such visual strategies were essential for legitimizing power. The images on the rocks of Wadi el Malik were not decorative—they were tools of statecraft, carved propaganda in a new political language.

The Desert as Periphery and Power

Why carve these declarations of sovereignty in such remote places? The desert wadis east of Aswan were not empty wastelands in the fourth millennium BC. They were hunting grounds, corridors for trade and expeditions, and sources of minerals. Claiming these spaces was a way of expanding influence beyond the Nile Valley, asserting control over resources and movement.

But there was also symbolic value. By carving their names and victories into the rock, rulers extended their presence into the very landscape. The desert itself became part of the political imagination of Egypt—a frontier claimed by kings who sought to unify the land under their command.

Rediscovering Forgotten Kings

The work of Morenz and Abu Bakr shows how modern scholarship continues to peel back layers of forgotten history. Using advanced digital techniques, researchers can now reveal faint carvings invisible to the naked eye. Photographs taken from multiple angles and processed by powerful software bring out details eroded by millennia of wind and sand.

These technologies are not just enhancing old finds—they are uncovering entirely new evidence. The discovery of the name “Scolopendra,” for example, added yet another dangerous animal to the roster of early kings. Each revelation helps flesh out the shadowy period before Egypt’s dynasties began, showing how ideas of kingship developed in both cultural centers and peripheral regions.

The Meaning of Violence and Order

The violent imagery of Scorpion trampling his enemies may strike modern viewers as brutal, but it carried profound symbolic meaning in its time. To early Egyptians, the king was not only a political leader but the guarantor of ma’at—the cosmic order that balanced chaos and harmony. Violence was framed not as cruelty but as the necessary act of maintaining stability. By vanquishing enemies, real or imagined, rulers presented themselves as defenders of civilization against the forces of disorder.

This ideology would endure throughout Egypt’s history. Later pharaohs, from Narmer to Ramses II, would also depict themselves smiting enemies in triumph. The roots of this imagery, however, lie in the carvings of the desert peripheries—silent witnesses to the dawn of pharaonic power.

A Call for Preservation

The inscriptions of Wadi el Malik are more than archaeological curiosities; they are foundational chapters in the story of human civilization. They reveal the earliest steps toward the concept of the state, the crafting of divine kingship, and the use of art as political power. Yet, these sites remain vulnerable. Weathering, looting, and neglect threaten to erase them before they can be fully studied.

Prof. Morenz has called for larger projects to preserve and research these carvings, envisioning not only academic study but also public engagement. Tours, visitor centers, and educational initiatives could make these sites accessible to wider audiences, ensuring that the story of Scorpion and his fellow rulers is not lost to the desert winds.

The Legacy of Scorpion

Though we know little about Scorpion as an individual, his presence in the rock art stands as a symbol of a pivotal moment in history. He and his peers were not yet pharaohs in the full sense of the word, but they were shaping the institution that would dominate Egyptian life for three millennia. Their carvings speak of ambition, creativity, and the human drive to legitimize power through image and ritual.

Today, standing in the desert where Scorpion once carved his name, one is struck by the sense of continuity. The sand may have shifted, the rocks may have worn, but the marks remain—a message across five thousand years. They remind us that kingship, statehood, and the visualization of power are not just abstract concepts but human inventions, born in specific times and places, and carried forward through symbols etched in stone.

In this way, Scorpion’s legacy lives on. Not only as a mysterious king of Egypt’s earliest days but as a testament to humanity’s enduring quest to define authority, identity, and meaning in a vast and uncertain world.