For generations, the story of early humans has been told as a tale of hunters—fearless, meat-craving wanderers who chased mammoths across ancient plains. But a new study published in the Journal of Archaeological Research paints a far more nuanced—and far more fascinating—picture of our distant past. Instead of relying mostly on meat, early humans carefully gathered, processed, and cooked a remarkable variety of plant foods. They were not the one-dimensional hunter-warriors often imagined but ingenious culinary experimenters discovering calories in unexpected places.

The research, led by scholars at the Australian National University and the University of Toronto Mississauga, traces a sweeping timeline of human innovation long before farms, fields, or domesticated crops existed. The image that emerges is deeply human: curious, adaptable, endlessly resourceful. It suggests our ancestors survived not simply through strength or strategy, but through creativity—and a willingness to eat almost anything the natural world could offer.

“We often discuss plant use as if it only became important with the advent of agriculture,” said Dr. Anna Florin, co-author of the paper The Broad Spectrum Species: Plant Use and Processing as Deep Time Adaptations. But the evidence, she explained, tells a different story.

The Ancient Kitchens Hidden in Deep Time

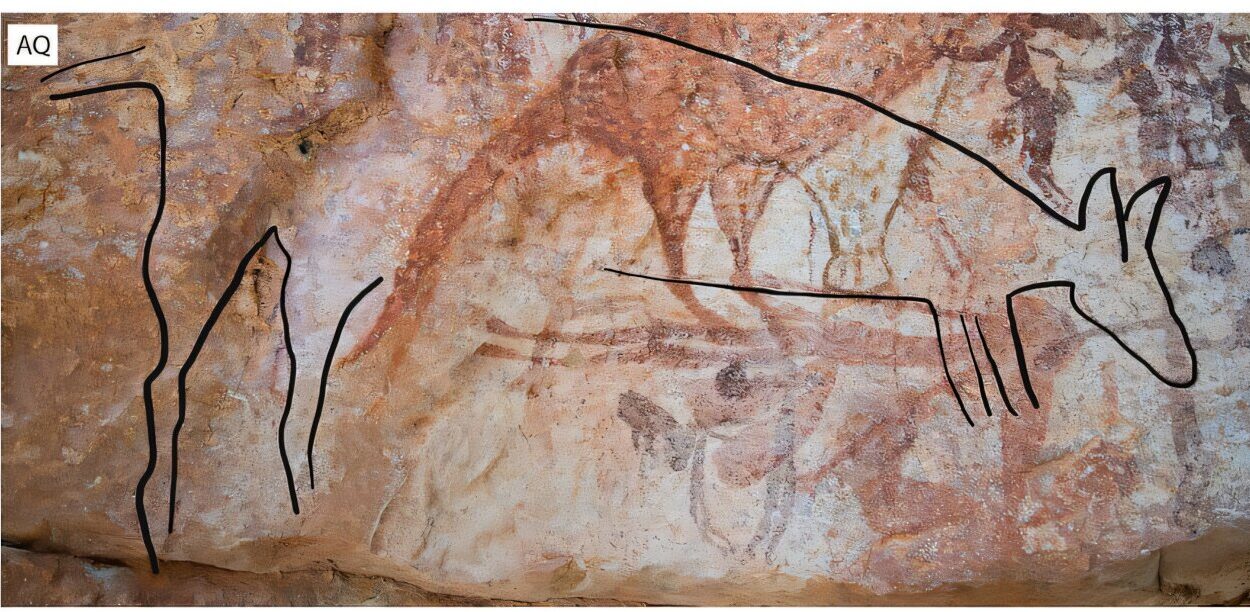

Archaeology has a way of challenging the familiar. What once looked like stones become pestles; what once seemed like debris reveals the faint fingerprints of cooking. Across sites worldwide, researchers are finding traces of plant-processing traditions that stretch tens of thousands of years into the past. Florin describes a world in which early humans weren’t passively grazing—they were experimenting, learning, and re-shaping their environments one meal at a time.

“However, new archaeological discoveries from around the world are telling us our ancestors were grinding wild seeds, pounding and cooking starchy tubers, and detoxifying bitter nuts many thousands of years before this.”

It’s a vivid imagining: small groups of early humans crouched around the fire, crushing seeds between stones, slicing roots to loosen their tough fibers, or leaching poisons from unfamiliar nuts until they were finally edible. Every step took knowledge. Every technique took time. And every meal was the result of cooperation and careful teaching passed from one generation to the next.

Far from the stereotype of primitive carnivores, our ancestors were solving complicated culinary puzzles long before agriculture codified food systems.

A Species Defined by Adaptability

The study introduces a compelling phrase: humans are a “broad-spectrum species.” This simple idea holds enormous power. It means our superpower has never been a preference for meat or plants—it’s been flexibility. When ecosystems shifted or climates changed, humans could follow. When animals migrated or populations thinned, people found sustenance elsewhere. Seeds, roots, nuts, fruits—if it contained energy, our ancestors learned how to make use of it.

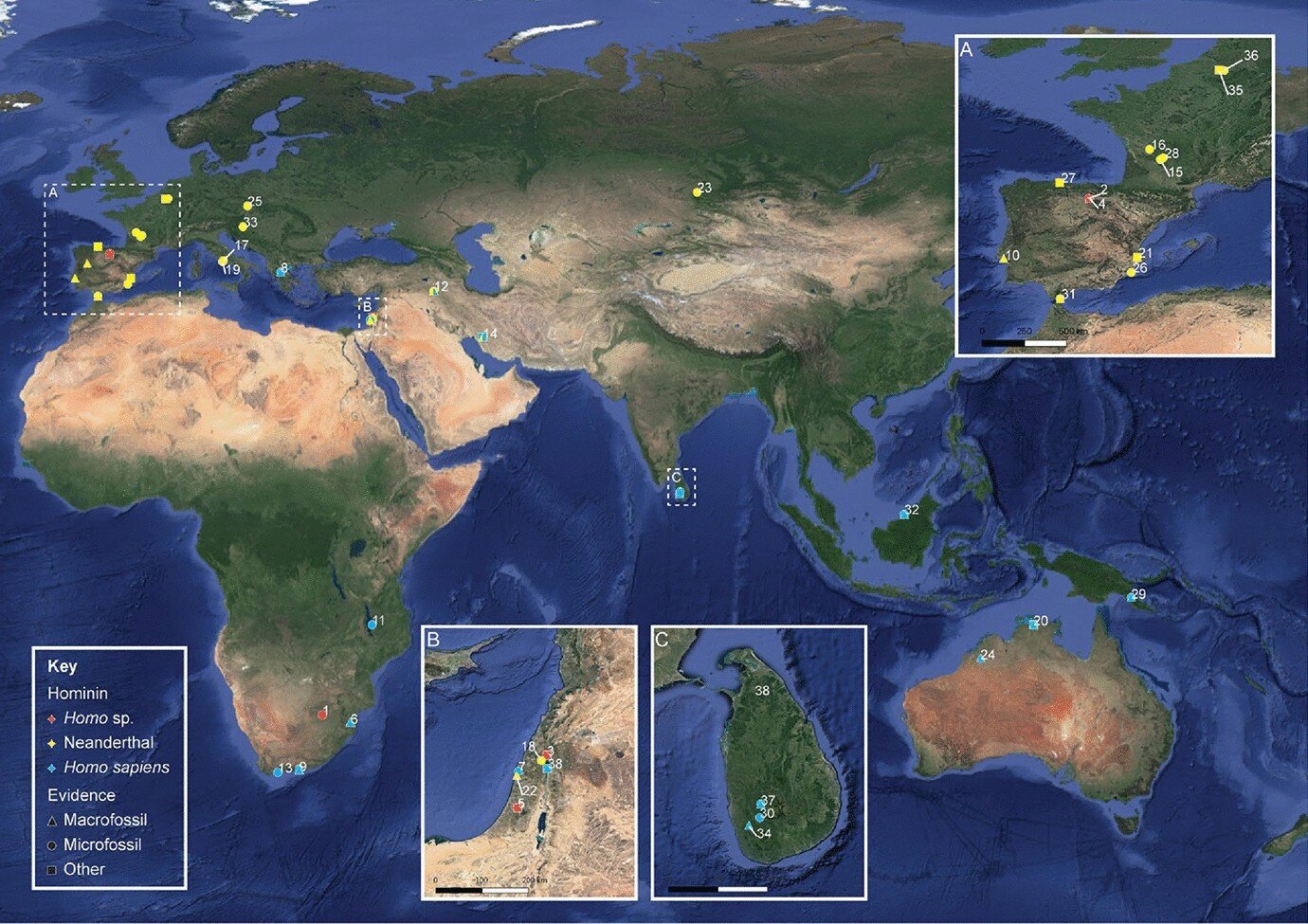

“This ability to process plant foods allowed us to unlock key calories and nutrients, and to move into, and thrive in, a range of environments globally,” said Dr. Monica Ramsey, co-author of the study.

The word unlock is key. Many plants in the ancient world were technically edible, but not immediately digestible or safe. Processing was the magic. Grinding broke tough seeds into powders. Cooking transformed hard tubers into soft, calorie-rich staples. Detoxifying made dangerous nuts safe to consume. Each innovation opened up new food resources, allowing early humans to survive in environments that other species couldn’t endure.

This versatility wasn’t just practical—it was transformative. Our ancestors moved across continents not because they chased only one type of prey, but because they could turn landscapes into pantries.

The First Food Innovators

The researchers emphasize that plant processing was not a minor supplement to early diets; it was central to human evolution. Long before the tools of agriculture—sickles, plows, baskets—there were stone grinders, pounding tools, hearths, and sharpened sticks. These early technologies reveal a pattern: humans didn’t simply gather; they engineered their meals.

The study captures this spirit vividly through a striking quote from Ramsey: “Our species evolved as plant-loving, tool-using foodies who could turn almost anything into dinner.”

It’s a line that transforms our understanding in an instant. To be a “foodie” in deep prehistory might seem humorous, but it’s surprisingly accurate. These early eaters were experimenting with flavors, textures, and techniques. They were discovering how heat changes a root, how crushing alters a seed, how soaking removes bitterness. They were paying attention.

And in doing so, they were not just feeding themselves—they were reinventing human biology. The nutrients unlocked through plant processing would have supported bigger brains, longer lifespans, and more complex social structures. Eating wasn’t only survival; it was innovation.

Why This Research Matters

This study invites us to rethink the way we imagine our origins. It challenges the simplistic narrative of the Paleolithic “caveman diet” and replaces it with something richer, more human, and more scientific. People survived not because they clung to a single, meat-heavy strategy, but because they embraced diversity—diversity in food, tools, environments, and knowledge.

Understanding this matters today more than ever. It reminds us that flexibility is our most ancient strength. It reconnects us with the creativity of our ancestors, whose experiments with wild seeds and tough tubers helped build the world we now inhabit. And it underscores that human evolution is not a story of rigid diets but of remarkable adaptability.

The new research shows that the roots of our species run deeper than hunting or gathering alone. They run into the firelit spaces where early humans learned to grind, cook, and taste the world around them—turning curiosity into nourishment, and nourishment into survival.

More information: S. Anna Florin et al, The Broad Spectrum Species: Plant Use and Processing as Deep Time Adaptations, Journal of Archaeological Research (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s10814-025-09214-z