When people think of ancient Egypt, images of the Great Pyramids of Giza and the golden mask of Tutankhamun immediately spring to mind. Towering monuments rise from the desert, silent witnesses to an age that has haunted human imagination for centuries. But Egypt was far more than its pyramids. Beneath the grandeur of colossal tombs and temples lies a hidden world, a vibrant civilization of farmers, artisans, scribes, priests, and families who sustained the rhythm of life along the Nile.

To focus only on pyramids is to miss the heartbeat of Egypt. This was a culture that endured for more than three thousand years, longer than almost any other in human history. Its secrets were not only locked in stone monuments but in humble houses, in pottery fragments, in prayers etched onto papyrus, and in the enduring relationship between people and the Nile. The hidden world of ancient Egypt is a story of resilience, creativity, faith, and humanity’s eternal quest for meaning.

Life Along the Nile

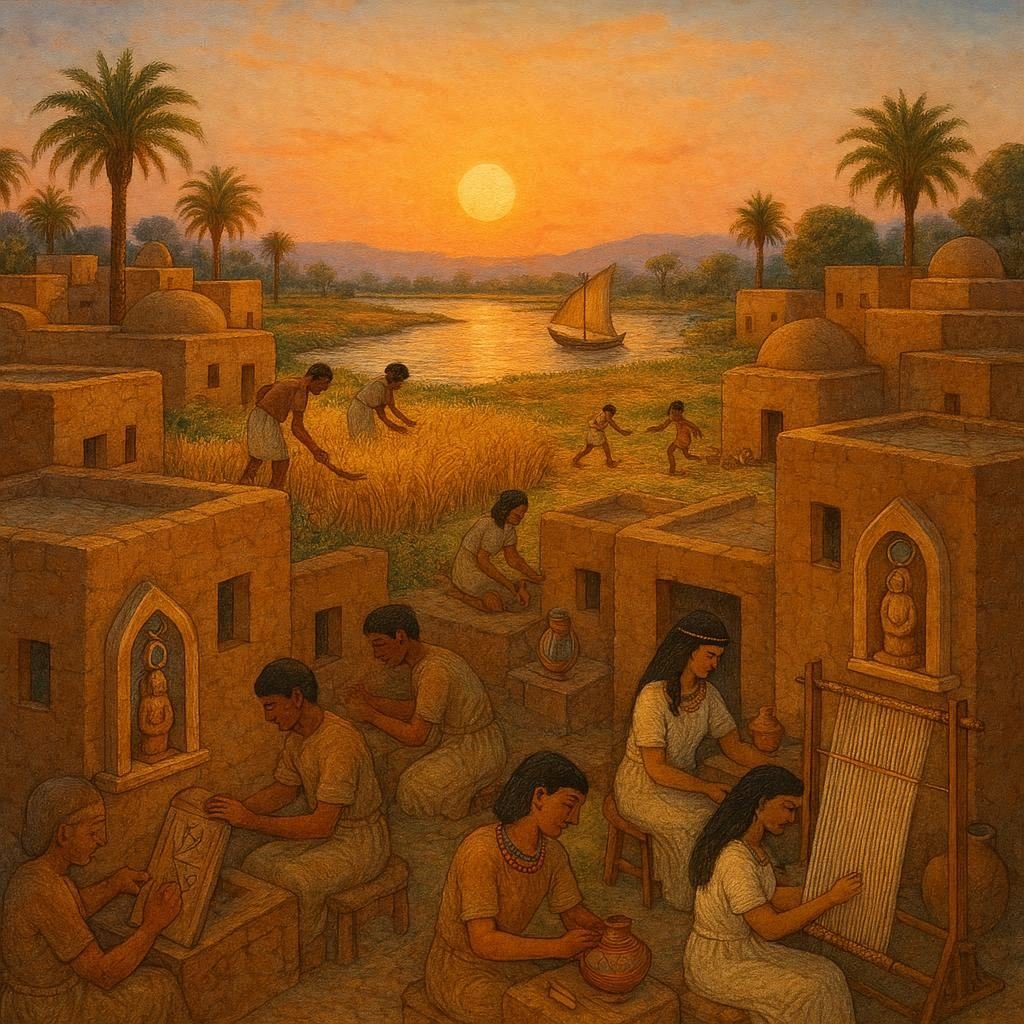

The Nile was more than a river; it was the very lifeblood of Egypt. Without it, there would have been no fertile land, no abundant crops, and no great civilization. Each year, the river swelled with the summer rains of East Africa, flooding the plains and depositing rich black silt that renewed the soil. Farmers waited eagerly for these floods, for the rhythm of their lives depended on them.

Beyond the pyramids, it was in the villages along the riverbanks that the true spirit of Egypt thrived. Here, farmers cultivated wheat, barley, and flax, while herders tended cattle, goats, and geese. Fields of papyrus swayed in the wind, providing the material for the world’s first paper. Children splashed in irrigation canals while their parents worked tirelessly under the sun. The cycle of planting and harvest bound Egyptians to the Nile in a relationship so profound that they saw it as a gift of the gods.

Egyptian farmers were practical innovators. They developed irrigation systems, waterwheels, and basin flooding techniques that allowed them to control the river’s bounty. Their agricultural success created surpluses that sustained cities, temples, and monumental building projects. The splendor of the pyramids was built on the shoulders of those who worked the soil.

The Houses of the Living

While pharaohs built houses of eternity in stone, ordinary Egyptians lived in houses of mud brick. These humble dwellings, perishable and fragile, rarely survive in the archaeological record, yet they formed the backdrop of daily life. Walls were plastered and painted, floors were smoothed, and reed mats covered living spaces. Roofs provided shade in the daytime and a place to sleep under the stars at night.

Families gathered around clay ovens to share bread and beer, the staples of the Egyptian diet. Beer, brewed from barley, was thick, nutritious, and consumed by all ages. Meals often included lentils, onions, cucumbers, dates, and figs, with fish from the Nile or meat when available. The simplicity of these meals tells a story of endurance and adaptation in a land both generous and demanding.

The rhythm of daily life was filled with work and ritual. Women ground grain, spun thread, and managed households, while men worked as farmers, artisans, or laborers. Children learned skills from their parents but also played with dolls, carved toys, and balls. In every humble act, the hidden Egypt reveals itself: a civilization not only of kings but of countless ordinary people who kept life flowing.

The Artisans of Deir el-Medina

If there was ever a place that opens a window into the hidden world of Egypt, it is Deir el-Medina. This village, tucked into the desert near the Valley of the Kings, housed the artisans who built and decorated the pharaohs’ tombs. Their lives are uniquely preserved in written records and archaeological remains, offering an intimate view of daily existence.

Here, scribes recorded work schedules, disputes, marriages, and even complaints about rations. We learn of craftsmen who meticulously carved hieroglyphs, painted brilliant murals, and chiseled the walls of royal tombs deep in the cliffs. But we also learn of their loves, quarrels, and fears. Letters speak of husbands missing their wives, of illnesses, of borrowing and lending. In one famous case, a worker went on strike—the first recorded labor strike in history—when food supplies were delayed.

Deir el-Medina shows that Egypt’s greatness was not only the product of kings but of skilled, creative, and very human individuals. It is in their personal writings and ordinary objects that we glimpse the humanity often lost behind monumental stone.

The World of Work and Craftsmanship

The wealth of ancient Egypt was not only measured in gold and temples but in craftsmanship. Beyond the pyramids, workshops hummed with activity. Metalworkers shaped copper into tools, goldsmiths hammered delicate jewelry, and potters molded clay into jars and lamps. Weavers produced linen so fine that some pieces rival modern fabrics in their quality.

Craftsmen were more than laborers—they were artists. Tomb paintings depict vibrant scenes of daily life, with detail so precise that modern scholars can reconstruct ancient agricultural and industrial practices. Wooden carvings, amulets, and musical instruments speak of a people who celebrated beauty, even in the smallest objects.

The artistry of Egypt was not confined to the elite. Ordinary households decorated their pottery, carved protective charms, and adorned themselves with beads of faience, a glazed ceramic material that sparkled like turquoise. Beauty and creativity were woven into the fabric of life, not reserved only for royalty.

The Language of the Gods

Hieroglyphs may seem mysterious and inaccessible, but for the Egyptians, writing was a living connection to the divine. They believed that words carried magical power, that to write something was to give it permanence in both the human and spiritual worlds. Temples and tombs were inscribed with prayers, hymns, and spells, ensuring that the dead could navigate the afterlife and that the gods would hear the voices of the living.

But writing was not only sacred; it was practical. Scribes recorded taxes, harvests, legal disputes, and letters. On scraps of pottery called ostraca, they practiced handwriting, scribbled notes, and even drew cartoons. The bureaucratic machinery of Egypt relied on scribes, who were respected for their knowledge and often enjoyed higher status than artisans or farmers.

The survival of papyri from ancient Egypt has given us medical texts, love poems, mathematical problems, and even humorous stories. These documents reveal a world of thought and imagination far beyond the solemn grandeur of pyramids. They remind us that Egyptians laughed, dreamed, and questioned, just as we do today.

The Spiritual Landscape

No aspect of ancient Egyptian life can be understood without its religion. To the Egyptians, the world was infused with divine presence. Every sunrise was the triumph of the sun god Ra over chaos, every flood a blessing from Hapi, the god of the Nile. Temples were not only places of worship but cosmic engines, where priests performed daily rituals to maintain harmony between gods and humans.

Ordinary Egyptians lived surrounded by the sacred. Amulets shaped like scarabs, eyes, or animals protected them from harm. Small household shrines honored protective deities like Bes and Taweret, who watched over families and childbirth. Death was not an end but a transition, and funerary practices—mummification, offerings, and tomb inscriptions—were ways of ensuring safe passage into eternity.

The hidden world of Egypt’s spirituality shows a people deeply concerned with balance, protection, and the eternal cycle of life and death. It was not only pharaohs who sought immortality; even the poorest aspired to join the ancestors in the afterlife, surrounded by fields of abundance.

Beyond the Pharaohs: Women in Egypt

Often overlooked in the shadow of kings, women in Egypt played crucial roles. While not fully equal to men, they had more rights than in many other ancient societies. Women could own property, initiate divorce, and run businesses. Queens like Hatshepsut and Nefertiti even ruled as powerful figures in their own right, leaving monuments that rivaled those of male pharaohs.

In households, women managed finances, raised children, and engaged in weaving and trade. Priestesses served in temples, and female musicians and dancers performed in religious ceremonies. The written record contains love poems celebrating women’s voices and medical papyri detailing gynecology and childbirth practices.

This hidden dimension of Egyptian life challenges modern assumptions, revealing a society where women were integral to both the domestic and public spheres, and where power, though often concentrated in male hands, was not entirely denied to them.

The Hidden Faces of Children

Children are rarely highlighted in discussions of ancient Egypt, yet they were central to its continuity. Tomb paintings depict children playing games, dancing, and accompanying their parents. Toys—dolls, carved animals, and balls—have been found in graves, testifying to the love and care families extended to the youngest members.

Children were also seen as vulnerable and in need of divine protection. Amulets, charms, and prayers were devoted to their safety. Education for boys, especially those of scribal or elite families, prepared them for careers in administration, while girls learned household skills. But childhood in Egypt was not all play. By adolescence, many children worked alongside parents in fields or workshops, contributing to family survival.

The hidden world of Egyptian children reminds us that behind the stone monuments were families striving to nurture and protect their future.

The Frontier Beyond Egypt

The grandeur of the pyramids often overshadows Egypt’s global connections, but this civilization was never isolated. Egypt traded with Nubia for gold, ivory, and exotic animals. From the Levant came cedar wood, prized for shipbuilding. Trade routes extended to Punt, a mysterious land likely in the Horn of Africa, bringing incense, myrrh, and exotic goods.

Egyptian soldiers campaigned abroad, merchants navigated the Mediterranean, and foreign communities lived within Egypt’s borders. Artifacts from as far as Mesopotamia and the Aegean show that Egypt was part of a vast web of exchange. This cosmopolitan aspect of Egypt’s hidden world shows a society that thrived not only on its own achievements but through interaction with the wider world.

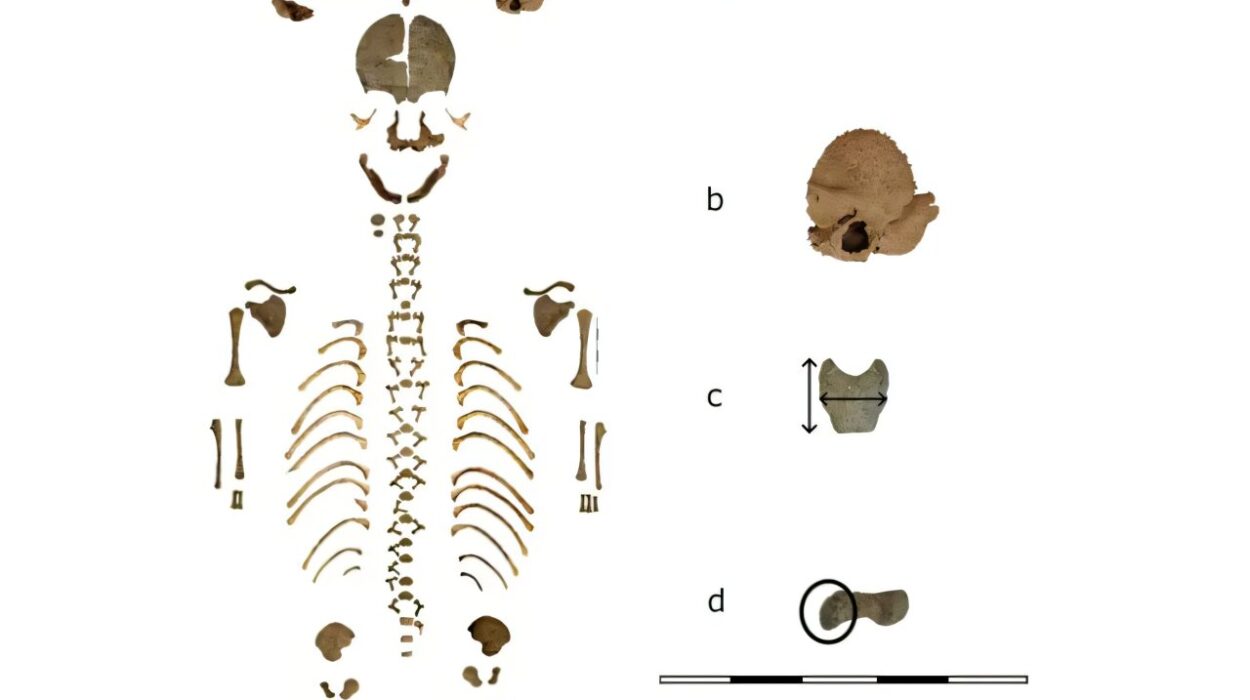

Archaeology and the Hidden Egypt

Much of what we know about ancient Egypt comes not from pyramids but from modest sites: workers’ villages, rubbish heaps, burial grounds, and abandoned houses. Archaeologists sift through these remains to reconstruct the hidden world. Plant seeds reveal diets, pottery shards trace trade, and graffiti etched by workers show private thoughts.

Modern technology has opened even more doors. Ground-penetrating radar reveals buried temples, DNA analysis traces the ancestry of mummies, and digital imaging uncovers faded inscriptions. Every discovery adds a new piece to the puzzle of a civilization far more complex than its monuments alone suggest.

Why the Hidden World Matters

The pyramids will always inspire awe, but they tell only one chapter of Egypt’s story. The hidden world—of farmers sowing crops, children playing by the Nile, artisans chiseling tombs, scribes writing love poems, and families worshiping household gods—reveals the humanity of a people who lived, loved, dreamed, and struggled.

By exploring beyond the pyramids, we see Egypt not only as a civilization of kings but as a society of individuals. We understand that its endurance was not only the result of monumental stone but of the daily resilience of countless lives woven together by the Nile.

In this hidden world, ancient Egypt ceases to be a distant, exotic marvel and becomes something far more intimate: a mirror of ourselves. Their concerns with love, family, survival, and meaning are timeless, reminding us that beneath the sands of time, the human spirit has always been the same.