Long before empires carved borders into maps, before conquistadors crossed oceans or cities sprouted from valleys, people walked into the heart of South America carrying only stone tools and dreams of survival. They came not with fanfare but with quiet persistence—small bands of hunter-gatherers trekking across landscapes that had never felt the press of human feet. These were the continent’s earliest pioneers, and they entered what is today Colombia by way of the north, spreading into the vast reaches of the southern continent in a migration as mysterious as it was momentous.

For decades, scientists have known that the first humans in South America arrived from the north. But the specifics—the when, the who, the how—have remained largely obscured beneath the layers of millennia. Now, an international team of researchers has peeled back the veil, uncovering the ghostly genetic traces of a population that once called the high plains around Bogotá home. Their story, recently published in Science Advances, is one of both profound discovery and haunting disappearance.

Bones in the Cloud Forest: Digging Into Deep Time

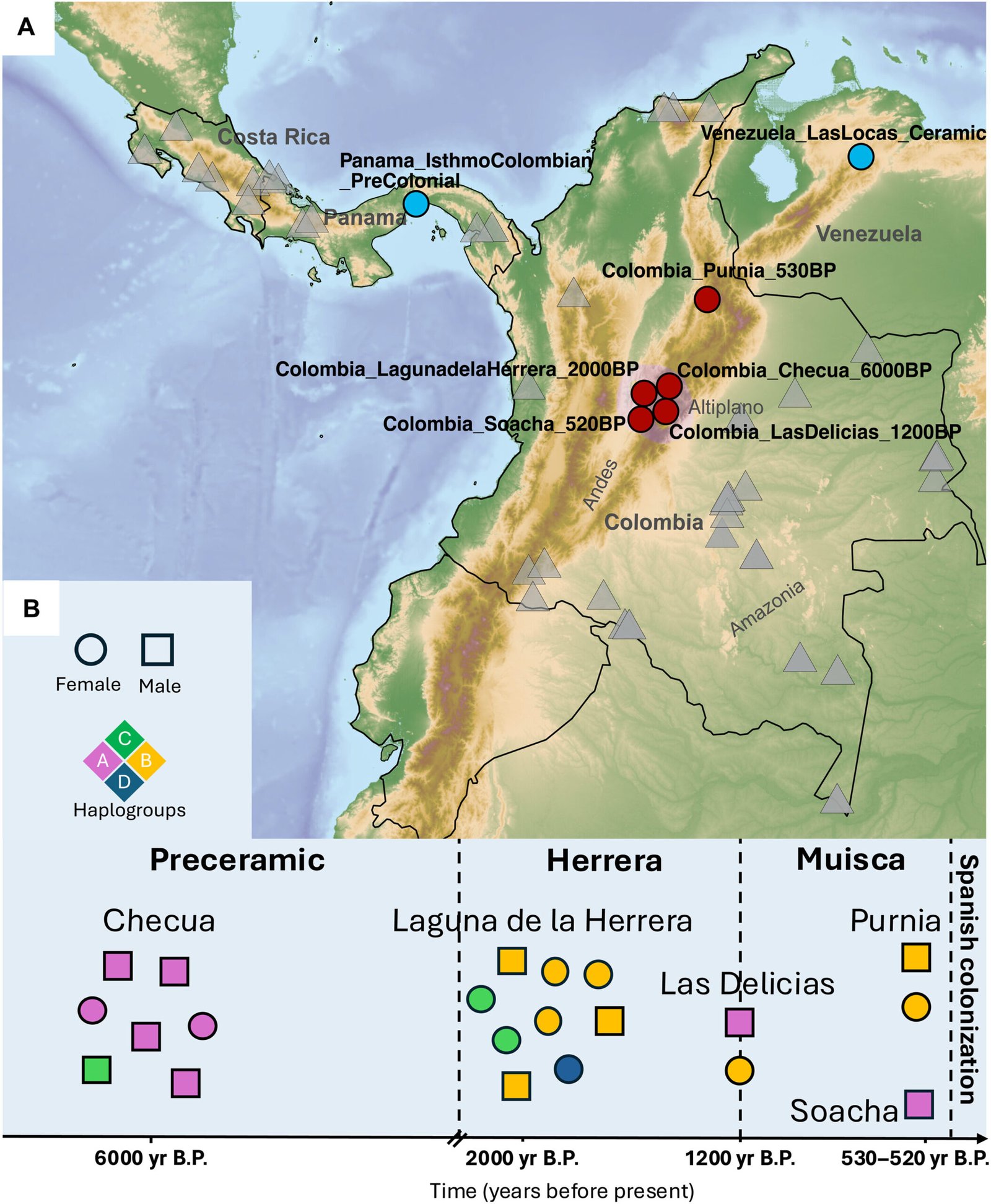

The high plateau of the Bogotá savanna, known as the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, is an environment of paradoxes—cold, high, and lush, ringed by mountains and veiled in mist. At 3,000 meters above sea level, this landscape sustained ancient peoples with its abundance of resources, including deer, tubers, and fresh water from Andean streams. It was here that researchers from the University of Tübingen, the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment, and Universidad Nacional de Colombia focused their investigation.

Their work revolved around 21 ancient individuals from five archaeological sites, including the Checua excavation just north of Bogotá. These were not the bones of kings or warriors, but of ordinary men, women, and children—people who lived, loved, and died long before written history arrived. Their bones, however, preserved a legacy their descendants did not: DNA.

The genetic material extracted from their teeth and bones covers a timespan of nearly 6,000 years, bridging the gap between the late Holocene and the eve of Spanish colonization. But it was the earliest genomes, dating back to 6,000 years ago, that told the most surprising story.

The First Colombians—And Their Vanishing Genes

The oldest individuals from Checua carried genetic signatures distinct from any later population in the region. These weren’t transient people—they belonged to a stable, rooted group of hunter-gatherers who had lived in the high plains for generations. Their genomes suggest they were part of the first great wave of humans to spread across South America, a population that diversified rapidly after arrival.

But then, something strange happened. As the team analyzed genomes from younger individuals—dating to around 2,000 years ago—the original genetic signatures were nowhere to be found. The descendants of those early pioneers had disappeared from the region’s gene pool as though swept away by an invisible tide.

Lead researcher Kim-Louise Krettek puts it plainly: “We couldn’t find descendants of these early hunter-gatherers of the Colombian high plains—the genes were not passed on.” This means that at some point before 2,000 years ago, a complete population replacement occurred. The ancient people of Checua vanished genetically, leaving behind only their bones and a scattering of stone tools.

A Newcomer Population Brings Change

Who replaced them? Genetic data from later individuals suggests the arrival of new migrants from Central America, who brought with them more than their DNA. These newcomers also introduced ceramic technology, agricultural practices, and linguistic traditions—particularly the Chibchan language family, still spoken today in parts of Central America and northern South America.

Andrea Casas-Vargas, co-author from the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, emphasizes the rarity of what they found. “That genetic traces of the original population disappear completely is unusual, especially in South America.” In other parts of the continent—especially in the Andes and the southern cone—there is often a strong genetic continuity across thousands of years, even in the face of dramatic cultural change.

But on the Altiplano, something different happened. The genes of the newcomers dominated completely. The population replacement was not partial or gradual; it was absolute. The people who followed—eventually giving rise to the famed Muisca culture—carried no genetic links to the ancient Checua hunter-gatherers.

The Muisca and the Illusion of Continuity

The Muisca civilization, known for its goldwork, agricultural terraces, and urban planning, flourished in the same region centuries later. When the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, they encountered a complex society of traders and artisans who worshipped the sun and moon and left offerings in sacred lagoons. From the outside, it might seem like a natural evolution from the earlier hunter-gatherer bands. But genetics reveals a more fractured legacy.

Despite the Muisca’s cultural depth and long habitation of the region, their ancestry derives not from the ancient Altiplano hunter-gatherers, but from that second wave of migrants. Still, this did not erase the land’s memory. Sacred sites remained sacred. Rivers still whispered the same names. Cultural traditions evolved, hybridized, and endured—but the bloodlines behind them had shifted.

Even so, the Muisca’s descendants remain deeply rooted in the land. The Guardia Indígena Muisca, a modern Indigenous group in the Bogotá region, were consulted before the study’s conclusion. For the scientists, this was essential. Genetics, after all, is not identity—and DNA should never be mistaken for cultural heritage.

Genetics Is Not Destiny

As Professor Cosimo Posth, senior author of the study, explains: “Questions about history and origins touch upon a sensitive area of the self-perception and identity of the Indigenous population. The genetic disposition must not be viewed as equal to cultural identity.”

That’s why the research team worked with the local community before finalizing their conclusions. The Muisca people today are culturally continuous with their ancestors—carrying languages, traditions, and spiritual practices that have endured colonization, displacement, and erasure. Even if the genetic story is more complex than once thought, the cultural lineage remains strong and unbroken.

This balance—between science and respect, data and meaning—is at the heart of modern archaeological genetics. Understanding ancient genomes can illuminate migrations and extinctions, but it must also be wielded with humility. People are more than their DNA.

Echoes in the Genome: What the Study Tells Us About South America

This research adds a new layer to the puzzle of how humans populated the Americas. It suggests that South America’s early demographic landscape was more dynamic than previously believed. While some regions show thousands of years of genetic continuity, others—like the Colombian Altiplano—reveal dramatic shifts.

It also raises new questions. What caused the population turnover? Was it driven by climate change, disease, conflict, or perhaps the advantages that came with ceramic technology and farming? The archaeological record hints at change, but does not yet tell a full story.

What’s clear is that the first wave of South American humans, those who left Asia, crossed into North America, and quickly spread south, was not monolithic. Different groups splintered off, evolved separately, and sometimes disappeared without a trace. Some, like the Checua hunter-gatherers, left behind only their bones and a few haunting strands of DNA.

Ancient Lives, New Revelations

The findings from Bogotá’s high plains underscore how much remains hidden in the human past. Until now, no ancient genome had ever been sequenced from Colombia. With this study, the country joins a growing map of genetic archaeology across the Americas, offering fresh insight into who lived where, when, and how those patterns changed over time.

But beyond the data points and evolutionary trees, there is something poetic about the discovery. A population that lived thousands of years ago, forgotten by history, has been found—not through legends or monuments, but in the silent code of their bones. They speak again, not in words but in sequences of nucleotides—whispers from the deep past, echoing through the lab.

They tell us that history is not always a straight line. That peoples rise, fall, and sometimes vanish. That culture can endure even when genetics does not. And that every new discovery opens new questions about who we are and where we came from.

Conclusion: The Future of the Past

In the cold, thin air of Colombia’s high plains, the bones of the past have told a story long buried under soil and time. The Checua people were among the first to call South America home, but they were not the last. Others came after them, bringing new ways of life and new identities, weaving a tapestry of cultures that continues to this day.

Science can illuminate these stories with unprecedented precision. But in doing so, it must also honor the human lives behind the data. The Indigenous peoples of Colombia, like the Guardia Indígena Muisca, are not just relics of a bygone past. They are living cultures with ancient roots and vibrant futures.

In the end, the mystery of the vanished Checua is not a tale of extinction, but transformation. Their legacy, now revealed in genetic code, reminds us that even in loss, there is connection—and that even in the most remote corners of prehistory, the human story is still being written.

Reference: Kim-Louise Krettek et al, A 6000-year-long genomic transect from the Bogotá Altiplano reveals multiple genetic shifts in the demographic history of Colombia, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ads6284