The human brain has long been celebrated for its remarkable ability to recognize the sound of a familiar voice. But a new study from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) introduces a twist to this familiar story: our brains aren’t listening only for human voices. They are also tuned, in a surprisingly specific way, to the vocalizations of chimpanzees. This discovery, published in the journal eLife, suggests that buried within our auditory cortex are pockets of neural machinery with roots far older than language itself.

The finding is more than a scientific curiosity. It is a clue—a tiny but vivid flash of insight—into the long evolutionary path that shaped how humans communicate today. And it all started with an experiment that asked a deceptively simple question: When we hear the calls of other primates, does our brain react?

When the Brain Remembers What Evolution Never Taught Us Directly

To explore the origins of voice recognition, researchers from UNIGE’s Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences decided to take a step back in evolutionary time. If our social and linguistic abilities emerged from ancient primate communication systems, the traces of those systems might still be visible in our brains.

Their strategy was straightforward but elegant. By comparing how the human brain responds to vocalizations from closely related species, the team hoped to uncover what we share—and what we no longer share—with our primate relatives.

They recruited 23 participants and exposed them to sounds from four different species. Human voices, of course, served as the baseline. Then came chimpanzees, our closest relatives not only genetically but also acoustically. Bonobos were included as well, equally close to us in ancestry but whose calls resemble birdsong more than speech. Finally, the researchers added macaques, a more distant species in both genetics and sound.

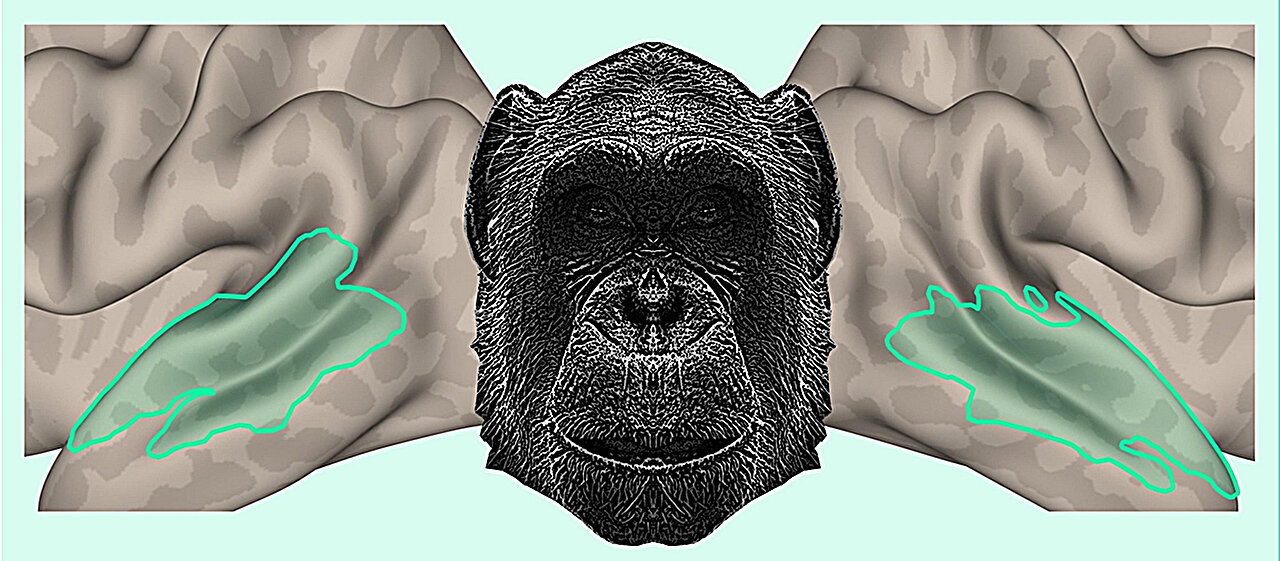

As the participants listened, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanned their auditory cortex. What the scientists were looking for wasn’t obvious from the outside; it required peering directly into the brain.

“Our intention was to verify whether a subregion sensitive specifically to primate vocalizations existed,” explains Leonardo Ceravolo, research associate at UNIGE’s Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences and first author of the study.

What they found was not just a simple “yes,” but something far more intriguing.

The Brain’s Hidden Preference

Deep in the superior temporal gyrus—a region known for processing language, music, and emotional tone—something lit up. The auditory cortex did indeed respond to non-human sounds. But the response wasn’t uniform. It had a preference.

“When participants heard chimpanzee vocalizations, this response was clearly distinct from that triggered by bonobos or macaques.”

The distinction mattered. Bonobos are just as close to us genetically as chimpanzees, but their calls are acoustically different. Macaques, distant from us in both ways, evoked even less of a specialized response. It was the combination of evolutionary closeness and acoustic similarity that stirred something unique inside the human auditory cortex.

Here, the brain revealed a kind of memory—not a conscious one, but an ancient, biological imprint of the sounds that once filled the environments of our shared ancestors. The fact that this sensitivity persists in adult humans is remarkable.

“We already knew that certain areas of the animal brain reacted specifically to the voices of their fellow creatures. But here, we show that a region of the adult human brain, the anterior superior temporal gyrus, is also sensitive to non-human vocalizations,” points out Leonardo Ceravolo.

The human brain, it seems, has kept one ear open to the past.

A Whisper From Before Language

The implications reach far beyond the question of which sounds activate which brain regions. This discovery touches on one of the deepest mysteries in science: How did human language evolve?

The fact that humans possess a region of the auditory cortex specifically sensitive to the vocalizations of close primates suggests that aspects of our voice-processing machinery didn’t emerge suddenly with articulate speech. Instead, they may be inherited features—neural scaffolding shared with great apes long before humans walked the earth with symbolic language.

These findings, therefore, reinforce the idea that our ability to analyze voices is ancient. Some of the skills used today to distinguish tones, rhythms, and emotional cues in speech may reach back millions of years, arising from the need to interpret the calls of social primates.

This research also hints at something closer to home: child development. If certain recognition systems are built into the architecture of the auditory cortex, they may help explain early feats of perception. For instance, babies recognize the voices of their caregivers even before birth, long before they understand words. Perhaps this early sensitivity is not learned from scratch but is instead supported by neural circuits preserved through evolution.

And so the story of this study is not only about a specialized response to chimpanzee calls. It is about continuity—about the threads that tie modern human communication to the deep past.

Why This Discovery Matters

Understanding how the brain processes vocalizations from close primate relatives offers a window into the origins of human communication. It suggests that the neural machinery supporting voice recognition did not appear suddenly but evolved gradually, building layer upon layer of complexity. This has implications for everything from the study of language emergence to the way infants learn to recognize familiar voices.

More broadly, this research invites us to reconsider how much of ourselves—our abilities, perceptions, and social tools—is inherited from a lineage that reaches far beyond humanity. The sensitivity of the auditory cortex to chimpanzee vocalizations is a reminder that our brains still carry echoes of the ancient world, shaped by millions of years of shared evolutionary history.

In learning how our minds react to these sounds, we are ultimately learning about ourselves: where we come from, how we communicate, and what pieces of our past still whisper inside the architecture of our brains.

More information: Leonardo Ceravolo et al, Sensitivity of the human temporal voice areas to nonhuman primate vocalizations, eLife (2025). DOI: 10.7554/elife.108795.1