Long before the first hominin took an upright step, long before the lineage that led to humans learned to shape tools or speak, there was a forest in what is now western Kenya. Dense, warm, and wet, this ancient Miocene jungle lay under the smoky gaze of the Tinderet Volcano, its soils soaked in life—and ash.

Today, that forest lives again—not through trees, but through fossils.

In a sweeping new study published in Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, a team led by Venanzio Munyaka has uncovered a treasure trove of early Miocene fossils at a site called Koru 16, offering a rare window into the world that cradled the ancestors of modern apes—and eventually, us.

“This is the environment where our story began,” says Munyaka. “It may not have been the cradle of humanity, but it was one of the earliest nurseries for the great apes.”

Beneath the Ash: A Forest Frozen in Time

The story begins more than 20 million years ago, when the now-extinct Tinderet Volcano repeatedly blanketed the land with ash. These volcanic layers, like pages in a book, sealed the landscape in remarkable detail. Each eruption became a timestamp, preserving leaves, tree stumps, bones, and soil in exquisite condition.

Over the course of a decade, from 2013 to 2023, Munyaka and his team excavated Koru 16’s secrets, carefully brushing away sediment to reveal what lay below. In total, they recovered fossils of around 1,000 leaves, remnants of numerous vertebrates, and an ancient world that pulses with echoes of the present.

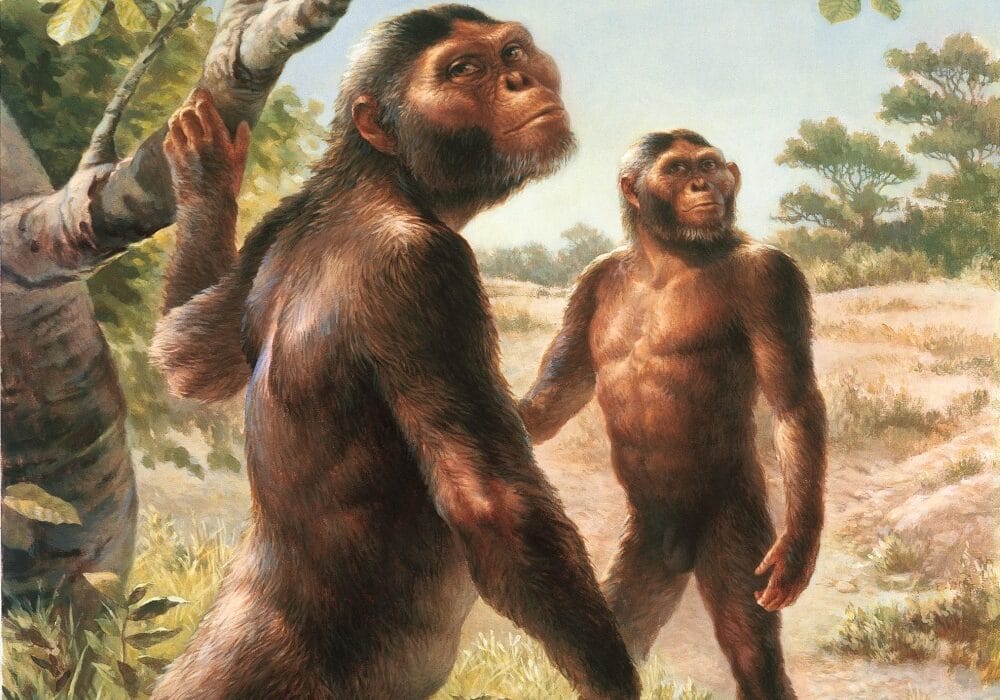

Among their discoveries were the fossil remains of a large-bodied ape species never seen before, alongside two previously known ape species. Together, these finds push the total vertebrate count at the site to 25—a diverse menagerie of pythons, rodents, primates, and other animals that once moved through the Miocene forest.

Reading the Leaves of the Past

To reconstruct what this lost world looked like, the researchers didn’t just rely on bones. They turned to the trees.

By analyzing the shapes and types of fossilized leaves, they could infer what kinds of trees once stood in Koru 16. The team also examined paleosols—ancient soils turned to stone—to decode the chemistry of the forest floor. Even fossil tree stumps, still rooted in place, whispered details about how dense the forest once was and how light might have filtered through its canopy.

What emerged was the portrait of a humid, seasonally warm forest. Rainfall levels were similar to those found in modern tropical and seasonal African forests. Yet, this forest was different. It likely hosted more deciduous plants—trees that lose their leaves seasonally—suggesting a dynamic, changing environment.

“This wasn’t a pristine, untouched rainforest,” explains Munyaka. “It was an evolving, fire-disturbed, sometimes-flooded landscape—complex and alive.”

And in that shifting ecosystem, early apes found their niche.

A Home for Apes, Shaped by Fire and Flood

Koru 16 was no quiet paradise. It was a place in flux, frequently disturbed by volcanic eruptions, wildfires, and floods. These periodic disruptions may have fragmented the forest, creating a patchwork of dense canopy and open clearings.

For the early apes of this region, that kind of environment may have been a catalyst for adaptation. Navigating a landscape of shifting light, scattered food sources, and variable terrain could have spurred changes in behavior, locomotion, and diet—traits that would echo down the evolutionary tree to modern great apes and humans.

Munyaka and his team believe that such “mosaic” environments, with both forest and open areas, may have played a key role in primate evolution, nudging some species toward new ecological strategies—perhaps even laying early groundwork for bipedalism.

“Our results suggest that it wasn’t just the forest that shaped these animals,” says Munyaka. “It was the dynamism of the forest—the constant change, the interruptions—that may have driven evolutionary innovation.”

The Tinderet Legacy: A Century in the Making

This isn’t the first time scientists have poked into the bones of Koru 16. In fact, the site has a storied history in the annals of paleoanthropology.

The first primate fossils from this area were uncovered in 1927, and in the mid-20th century, famed anthropologist Louis Leakey led several expeditions here. Leakey, whose work revolutionized our understanding of human evolution, was drawn to the region’s rich fossil record. But many questions remained unanswered—until now.

Armed with modern tools and techniques, Munyaka’s team is not only filling in gaps but painting entire chapters of evolutionary history that had been lost to time.

“We’re not just identifying species—we’re reconstructing ecosystems,” says Munyaka. “We’re learning how climate, vegetation, and geological upheaval shaped the biological world millions of years ago.”

Lessons from a Lost Forest

Why does a 20-million-year-old forest in Kenya matter to us today?

Because the forces that shaped that ancient ecosystem—climate shifts, volcanic activity, habitat fragmentation—still operate today. And as the modern world grapples with deforestation, global warming, and biodiversity loss, the past offers both warning and wisdom.

Understanding how early apes thrived or failed in such environments can help scientists predict how species, including our own, may respond to the upheavals of the present and future. Evolution is not just about survival—it’s about adaptability in the face of constant change.

“Studying the past gives us context for our future,” Munyaka reflects. “These fossils remind us that Earth has always been dynamic—and that life’s response to that dynamism is what shapes the course of evolution.”

A Forest Remembered

The forest of Koru 16 is long gone. Its roots are now stone, its canopy turned to dust. But thanks to the persistent work of paleontologists, it breathes once more—in scientific journals, in museum displays, and in our expanding understanding of where we come from.

Somewhere in the ash of an ancient volcano, the seeds of humanity were planted. And as scientists continue to sift through the remnants, they bring us closer to the origins not just of apes, but of what it means to be human.

Reference: Venanzio Munyaka et al, Insights on the Paleoclimate and Paleoecology of an Early Miocene Hominoid Site: A Multiproxy Study From Koru, Western Kenya, Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2025PA005152