In the dusty drawers of a Mongolian institute, buried beneath decades of neglect and mislabeling, lay the bones of a forgotten beast—one that would turn out to be a royal addition to the tyrannosaur family. Not a king like the towering Tyrannosaurus rex, but a dragon prince: slender, swift, and critical to rewriting the origin story of one of Earth’s most iconic predators.

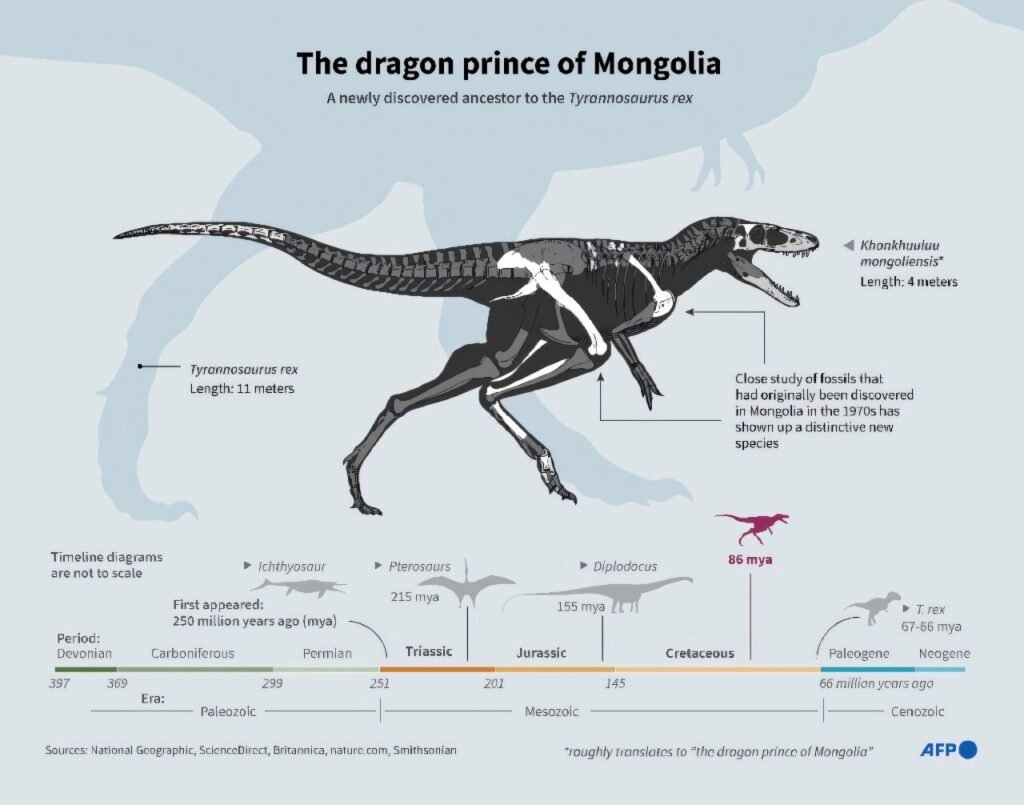

This newly identified dinosaur, now named Khankhuuluu mongoliensis, was announced Wednesday in the journal Nature. More than just a fresh face in paleontology, this 13-foot-long, horse-sized predator has become a key to understanding the messy, globe-spanning history of tyrannosaurs.

Its discovery—half a century after the bones were unearthed—sheds new light on the journey these creatures took between continents, and how one branch of the family tree gave rise to the colossal T. rex, ruler of prehistoric North America.

A Dinosaur Rediscovered

The story begins in the sun-scorched badlands of southeastern Mongolia in the 1970s, when a team of paleontologists from the Mongolian Academy of Sciences excavated several partial dinosaur skeletons. Believing them to belong to a known species, Alectrosaurus, the fossils were tucked away in the Institute of Paleontology in Ulaanbaatar.

There they sat, untouched and unidentified, for more than 50 years.

That is, until Jared Voris, a Canadian Ph.D. student with a keen eye and a curious mind, began combing through the drawers during a research trip to Mongolia.

“He noticed something strange,” said Darla Zelenitsky, a University of Calgary paleontologist and co-author of the new study. “The bones didn’t look quite like Alectrosaurus. They were well-preserved and had distinct features that set them apart.”

As Voris and his colleagues looked closer, they realized they weren’t dealing with one animal, but two partial skeletons from a previously unknown species. The find was both thrilling and sobering—a reminder that even some of the most significant fossils can sit unseen in museum collections for generations.

“It is quite possible that discoveries like this are sitting in other museums that just have not been recognized,” Zelenitsky said.

A Sleek Ancestor of a Giant

While Khankhuuluu mongoliensis doesn’t match the bone-crushing bulk of its famous descendant, it was no mere footnote in tyrannosaur evolution. Measuring about four meters in length (roughly 13 feet) and weighing around 750 kilograms (about three-quarters of a tonne), it would have been the size of a large horse—powerful, fast, and lethal in its own time.

“It’s smaller than T. rex, of course, but still a formidable predator,” said Zelenitsky. “It was likely agile and quick, possibly more suited to chasing down prey than ambushing it.”

The name Khankhuuluu mongoliensis pays tribute to its homeland—and to its place in the dinosaur dynasty. Roughly translated, it means “dragon prince of Mongolia,” placing it just below the tyrant king on the evolutionary ladder.

Mapping a Transcontinental Legacy

What makes Khankhuuluu truly remarkable, however, is not just its physique but what it reveals about how tyrannosaurs evolved and moved across ancient Earth.

For decades, the tyrannosaur family tree was a chaotic web of branches. Scientists knew the apex predator Tyrannosaurus rex lived in North America around 66 million years ago, right before the asteroid impact that ended the reign of the dinosaurs. But the origin of T. rex’s immense size and dominance remained a mystery.

The new fossil helps fill that gap.

Roughly 20 million years before T. rex ruled the west, Khankhuuluu or one of its close relatives likely crossed a land bridge that once connected Asia and North America—where Siberia kissed Alaska. That ancient migration kickstarted the tyrannosaur’s North American saga.

From there, tyrannosaurs diversified across the continent, giving rise to a variety of species. Eventually, one of these giants made its way back to Asia, where two distinct subgroups emerged: one small and slender, the other massive and bone-crunching.

Among the latter was Tarbosaurus, a behemoth nearly the size of T. rex itself, which prowled through ancient Mongolian forests.

And then, in a final migration, one colossal tyrannosaur returned to North America—an evolutionary homecoming that led directly to the birth of Tyrannosaurus rex.

Tyrants of Time—and of Chance

The lineage of T. rex, it turns out, wasn’t a single straight climb to the top of the food chain. It was a turbulent back-and-forth across continents, shaped by changing climates, shifting continents, and the random chance of fossil preservation.

And for all its fame, T. rex didn’t rule long. It lived for just around two million years—a flash in geological time—before a mountain-sized asteroid crashed into what’s now the Gulf of Mexico, triggering a mass extinction that wiped out three-quarters of life on Earth.

Birds are the only dinosaurs that survived.

“T. rex was the end of the line,” said Zelenitsky. “And now we’re beginning to see just how complex and fascinating that family line really was.”

Hidden Dragons in Forgotten Drawers

The rediscovery of Khankhuuluu mongoliensis is more than a triumph of taxonomic revision—it’s a call to action for paleontologists worldwide. Museums, particularly in fossil-rich regions like Asia, are treasure troves of data waiting to be unearthed, not from the ground, but from cabinets and boxes, dusty shelves and forgotten storage rooms.

“It makes you wonder how many other fossils are just sitting there, misidentified, waiting for someone to take a closer look,” Zelenitsky said.

With the right eyes and the right questions, even a drawer in a quiet institute can yield the next chapter in the epic saga of life on Earth.

And thanks to a curious student, a half-century-old mistake, and the bones of a dragon prince, that saga just got a little richer—and a lot more fascinating.

Reference: Jared T. Voris et al, A new Mongolian tyrannosauroid and the evolution of Eutyrannosauria, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08964-6.