Buried beneath layers of Siberian permafrost, two tiny creatures lay untouched for nearly 14,000 years. Their small bodies, wrapped in dark fur and cradled by the icy earth, were so well preserved that the whiskers still lingered on their muzzles. When modern ivory hunters stumbled upon the first of these pups in 2011 while searching for frozen mammoths near the village of Tumat, they had no idea they were unearthing one of the most extraordinary paleo-canine finds in decades.

Four years later, a second pup surfaced just meters away—nearly identical in appearance and condition. Dubbed the “Tumat puppies,” these Ice Age canines quickly captured scientific curiosity and global fascination. Their pristine preservation raised a tantalizing question: Were these the remains of early domesticated dogs, evidence of ancient companionship between humans and canines? Or were they something wilder?

Now, after more than a decade of mystery and speculation, a new study published in Quaternary Research has delivered a definitive—and surprising—answer.

They were not dogs at all. They were wolves.

Sisters of the Ice

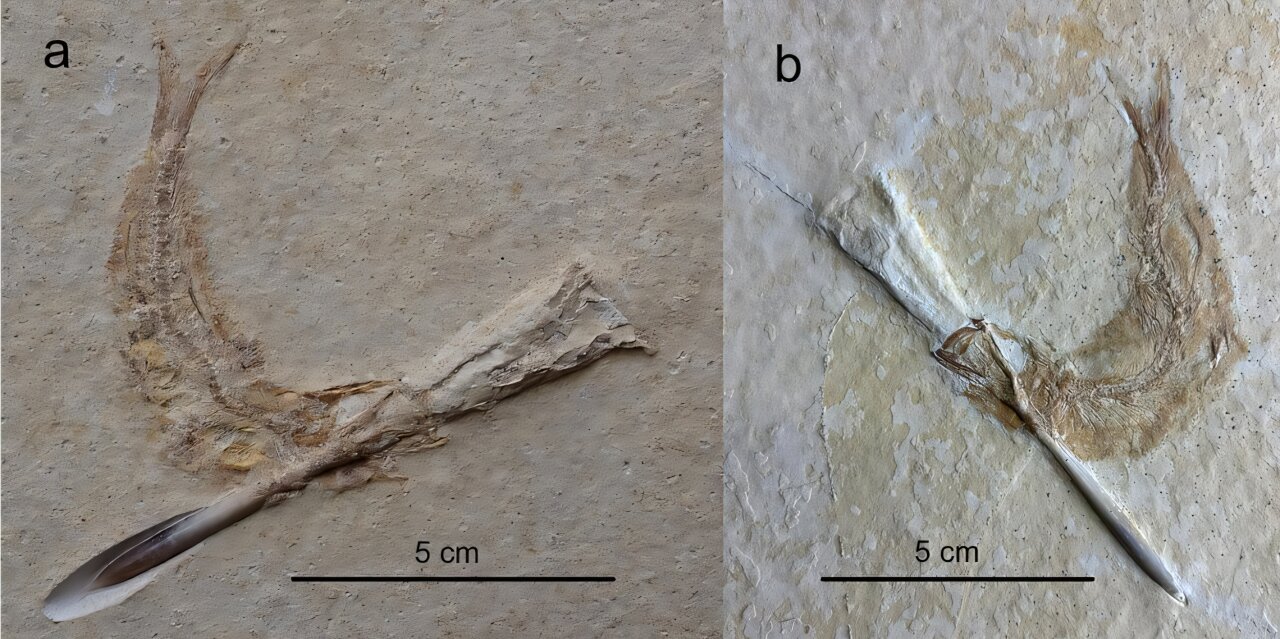

Led by a multinational team of archaeologists, paleontologists, evolutionary biologists, and natural scientists from across Europe, Russia, and the U.K., the researchers applied cutting-edge genetic sequencing, radiocarbon dating, and anatomical analysis to the remarkably preserved specimens.

What they found was both haunting and enlightening. The two pups were not only wolves, but sisters—female littermates who likely perished together in the safety of their den. There were no signs of trauma or injury, no marks of predation or disease. Instead, the evidence suggests a sudden landslide buried them alive, sealing them in a time capsule of ice and silence.

“This kind of preservation is astonishing,” said a team spokesperson. “We don’t often get this kind of window into the Pleistocene. These animals look like they were just sleeping.”

The state of their remains allowed for unprecedented insight—not just into their species, but into their lives, their final meals, and the world they inhabited.

Woolly Rhinos and Wolf Pups

Among the most astonishing discoveries came not from bones or fur, but from the contents of their tiny stomachs.

Inside one of the pups was something almost unthinkable: tissue from a woolly rhinoceros.

For decades, paleontologists believed that even adult wolf packs couldn’t take down the massive, horned giants that once roamed Ice Age steppes. These rhinos were formidable and thick-skinned—standing up to two meters tall and weighing over a ton. But here was clear biological evidence suggesting that somehow, these wolves had access to rhino meat.

“The presence of woolly rhinoceros tissue stunned us,” the study authors noted. “It challenges assumptions about Ice Age predator-prey dynamics. While it’s possible the pups scavenged a carcass, it also opens the door to rethinking how powerful and resourceful these early wolves might have been.”

The team carefully noted that the rhino tissue could have come from a calf rather than an adult, or from a partially decomposed animal—both scenarios within the realm of possibility for opportunistic predators like wolves. But regardless, the presence of such prey in a juvenile’s stomach hints at the strength, coordination, and adaptability of these ancient animals.

Milk, Plants, and Survival

Alongside the rhino tissue, researchers found evidence of milk in the pups’ digestive systems. This confirmed that the siblings were not yet fully weaned—infants, dependent on their mother for survival. Their final meals, tragically, may have been some of their first.

Plant material was also detected, an expected but significant detail. Modern wolves occasionally ingest plant matter, whether intentionally or by accident while feeding on herbivore stomach contents. This varied diet further cements the evolutionary continuity between modern and Ice Age wolves.

Taken together, these findings paint a poignant picture. The Tumat pups were nursing-age, possibly just weeks old, being raised in a den by a mother who likely had other offspring. A sudden environmental catastrophe—perhaps triggered by melting permafrost or shifting ice—collapsed the den and sealed their fate.

It also raises the intriguing possibility that more pups remain entombed nearby, their stories still locked beneath frozen soil.

Dogs, Wolves, and the Human Heart

The Tumat puppies had long stirred debate about when and where dogs first split from wolves. Dog domestication is one of humanity’s greatest evolutionary alliances, a partnership that altered both species forever. Earlier theories suggested the Tumat specimens might represent an early stage in that bond—perhaps proto-dogs, already beginning to shift genetically and behaviorally alongside humans.

Part of this assumption stemmed from their black fur, a trait once believed to have emerged exclusively in domesticated dogs. But this new research reveals that ancient wolves may have also carried this genetic trait, further blurring distinctions once thought to be clear-cut.

The pups’ canine charm also likely influenced perceptions. They were so small, so familiar. Their curled bodies, soft ears, and preserved fur evoked something tender in modern viewers—a reminder of our enduring bond with domesticated dogs.

But even as the DNA says “wolf,” the emotional reaction remains. These were living beings, social and intelligent, who died suddenly and whose preservation offers us a rare gift: a direct, tactile connection to a world long gone.

A Glimpse into the Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene, stretching from roughly 126,000 to 11,700 years ago, was a time of dramatic climatic shifts and ecological upheaval. Megafauna roamed the plains—woolly mammoths, saber-toothed cats, and massive elk—and early humans were learning to navigate a world of fire, stone, and survival.

In this frozen, perilous world, wolves were apex survivors—clever, cooperative hunters whose lineage would eventually diverge, giving rise to the loyal companions that share our homes today.

The Tumat wolf pups offer not just data, but depth. They invite us to step out of our modern moment and into a silent, snow-laced world where survival was a daily gamble, and even the tiniest creatures bore the marks of evolution, adaptation, and fate.

A Story Still Unfolding

This discovery is far from the end of the story. As permafrost continues to thaw—accelerated by global climate change—more prehistoric creatures are likely to emerge. Some will offer new insights into Ice Age ecosystems; others may reshape long-held scientific paradigms.

And somewhere, perhaps not far from Tumat, more pups may lie hidden in the cold earth, waiting to tell their story.

Until then, the sisters of the Ice Age rest in their ancient cradle, preserved not just by time, but by the unrelenting curiosity of those determined to understand our planet’s deep, mysterious past.

Reference: Anne Kathrine Wiborg Runge et al, Multifaceted analysis reveals diet and kinship of Late Pleistocene ‘Tumat Puppies’, Quaternary Research (2025). DOI: 10.1017/qua.2025.10