Long before the word “evolution” existed, human beings gazed at the natural world with awe and puzzlement. They observed the flight of birds, the metamorphosis of insects, the strange bones unearthed from deep in the ground, and asked themselves: where did life come from? Why are there so many forms? Are species fixed and eternal, or do they change?

These questions are as old as thought itself. From the earliest myths and oral traditions, people tried to explain the diversity of life through divine creation or spiritual transformation. Yet even in ancient times, a few thinkers dared to imagine a world in motion—a world in which life might change.

The Greek philosopher Anaximander, who lived in the 6th century BCE, proposed that life began in the sea and that humans might have evolved from fish-like creatures. Though he lacked evidence and his ideas were steeped in mythology, this early suggestion planted the seed for what would become a revolution in human understanding.

It would take over two millennia for that seed to bloom.

Aristotle’s Order and the Ladder of Life

By the 4th century BCE, the towering intellect of Aristotle dominated natural philosophy. A student of Plato and tutor to Alexander the Great, Aristotle’s influence would shape science for centuries. He believed that all living things could be arranged in a hierarchy, from the simplest to the most complex—a “Great Chain of Being” in which plants lay at the bottom, followed by animals, and culminating in humans.

To Aristotle, species were fixed and immutable. Each organism had a purpose, a final cause, and was created to fulfill a specific role. This view harmonized well with religious doctrines, particularly when Christianity spread throughout the Roman world. Over time, the Aristotelian worldview merged with theological teachings, solidifying the belief that life was static and unchanging.

For more than a thousand years, this belief would remain largely unchallenged.

Medieval Silence and the Rise of Natural Theology

During the Middle Ages, scientific inquiry slowed in Europe as religious dogma took precedence over empirical observation. However, natural curiosity never vanished. Monks and scholars in monasteries preserved ancient texts and quietly continued to study the natural world, often viewing their work as a form of devotion.

With the rise of natural theology in the Renaissance and early modern period, thinkers began to ask not just what life was, but how it worked. Natural theologians believed that studying nature was a way to understand the mind of God. Species were still considered fixed, but the intricate complexity of organisms was seen as evidence of divine design.

The metaphor of the watchmaker—first used in this context by theologians—suggested that just as a watch required a watchmaker, so too must the complex machinery of living beings require a divine designer.

This belief was beautifully expressed in the works of William Paley, whose 1802 book Natural Theology argued passionately for the idea of creation by design. Paley’s analogies and eloquence would later be read by a young Charles Darwin and wrestled with deeply.

The Enlightenment and the Gentle Stirring of Doubt

The Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries ushered in a wave of skepticism, logic, and scientific inquiry. The age of reason sought natural explanations for natural phenomena. It was a time when science began to free itself from the heavy cloak of religious orthodoxy.

Naturalists like Carl Linnaeus, Georges-Louis Leclerc (Comte de Buffon), and Erasmus Darwin—grandfather of Charles Darwin—began to question the rigidity of species. Linnaeus, known for inventing the modern system of classification, still believed in the fixity of species, but his very system of grouping similar organisms hinted at common ancestry. Buffon boldly suggested that species might change over time due to environmental influences, though he stopped short of proposing a mechanism.

Erasmus Darwin, a physician and poet, speculated that all warm-blooded animals could have descended from a single common ancestor. His writings were imaginative and often metaphoric, blending science with poetry. While lacking the rigorous methodology of later scientists, Erasmus Darwin’s ideas created intellectual space for the next great leap.

Lamarck and the First Formal Theory of Evolution

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, a French biologist working in the early 19th century, was among the first to propose a coherent theory of how species change. Lamarck suggested that organisms adapt to their environment during their lifetime and pass these acquired traits on to their offspring. He called this the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

According to Lamarck, giraffes developed long necks because their ancestors stretched to reach higher leaves, and this habit gradually transformed their anatomy over generations. While his mechanism would later be proven incorrect, Lamarck’s core belief—that species are not fixed—was revolutionary.

He also introduced the idea of complexity increasing over time, envisioning a natural tendency for organisms to progress toward greater perfection. In the rigid world of scientific orthodoxy, Lamarck’s vision was mocked, misunderstood, and dismissed. Yet he had dared to imagine what others had only hinted at: a dynamic world of changing life.

The Geological Foundations of Change

Around the same time, geology was emerging as a science that would provide vital clues to the history of life. James Hutton and later Charles Lyell proposed that the Earth was far older than previously imagined and that its features were shaped by slow, continuous processes over vast timescales.

This concept—uniformitarianism—suggested that the forces shaping the planet today, such as erosion and sedimentation, had been at work for millions of years. Lyell’s book Principles of Geology became a foundational text, and when Charles Darwin read it on his voyage aboard the HMS Beagle, it changed his view of time and nature.

Without geology’s deep timescale, evolution would be impossible. Change requires time, and Darwin would need every moment of that ancient clock.

Darwin’s Quiet Revolution

When Charles Darwin set sail in 1831, he was a 22-year-old naturalist with a passion for beetles and a vague interest in the natural sciences. The voyage of the HMS Beagle would last nearly five years and take him around the world, but it was the Galápagos Islands that would etch themselves into scientific history.

Darwin observed finches with different beak shapes on different islands, tortoises with subtly varying shells, and fossil remains of extinct animals similar to modern species. He began to suspect that species were not immutable.

Back in England, he spent more than two decades refining his theory. Influenced by Thomas Malthus’s essay on population, Darwin saw that in nature, more individuals are born than can survive. Those with favorable traits are more likely to live and reproduce. Over generations, these traits accumulate. This process, he realized, was the engine of evolution.

In 1859, he published On the Origin of Species, a masterwork of scientific thought. The book introduced the concept of natural selection: the idea that nature itself selects the most advantageous traits for survival. Darwin’s theory elegantly explained how complex life could emerge without divine intervention or Lamarckian effort.

The reaction was explosive. Some embraced his ideas with wonder. Others, especially religious authorities, were horrified. The idea that humans might share ancestry with apes challenged the very foundations of human exceptionalism.

Yet Darwin had pulled back the curtain on life’s grand mechanism.

The Synthesis of Genetics and Evolution

Darwin had many strengths, but he lacked an understanding of heredity. How were traits passed from parent to offspring? Without this piece, evolution was a compelling idea, but it lacked a mechanism of transmission.

Unbeknownst to Darwin, a monk named Gregor Mendel was quietly performing experiments with pea plants in a monastery garden in what is now the Czech Republic. Through careful breeding, Mendel discovered the basic laws of inheritance—dominant and recessive traits, segregation, and independent assortment.

His work was published in 1866 but went unnoticed for decades. In 1900, three scientists independently rediscovered Mendel’s work, and biology entered a new era.

Throughout the early 20th century, scientists like Ronald Fisher, J.B.S. Haldane, and Sewall Wright fused Mendelian genetics with Darwinian selection. This marriage became known as the modern synthesis, and it established evolution as the central unifying theory of biology.

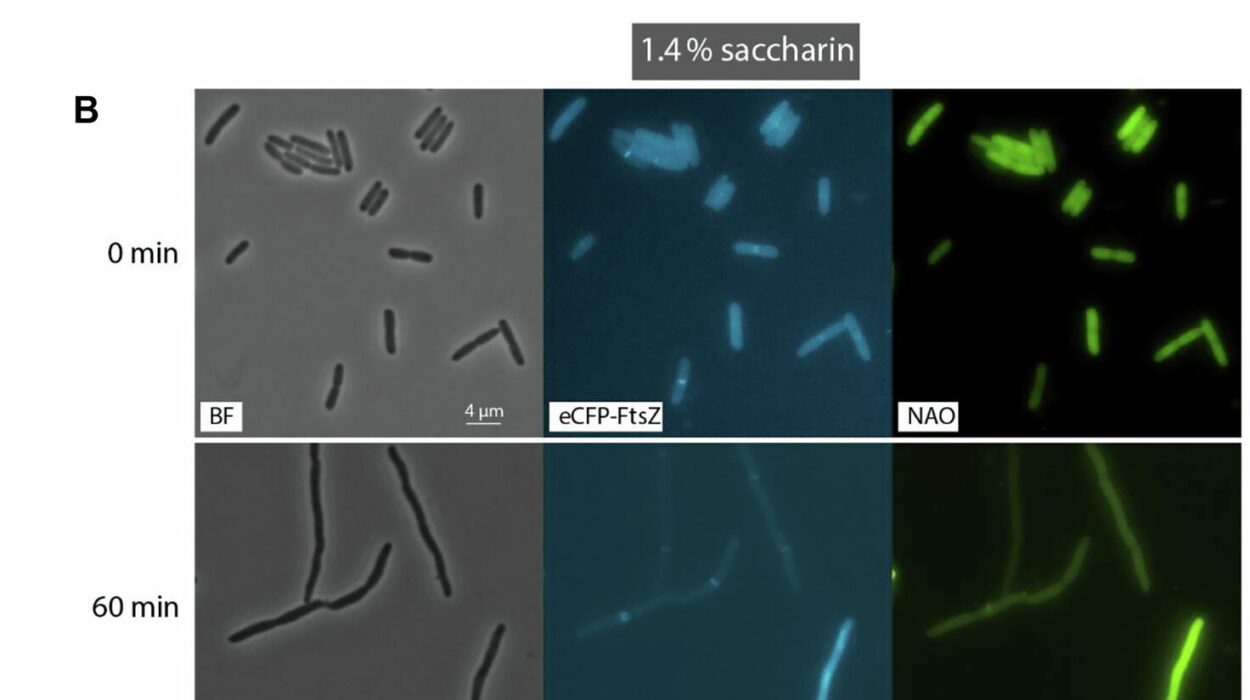

Now evolution had a mechanism—genes—and a means of variation—mutation. Natural selection could now be observed not just in fossils and fieldwork, but in the very code of life.

The Molecular Era and the Genetic Revolution

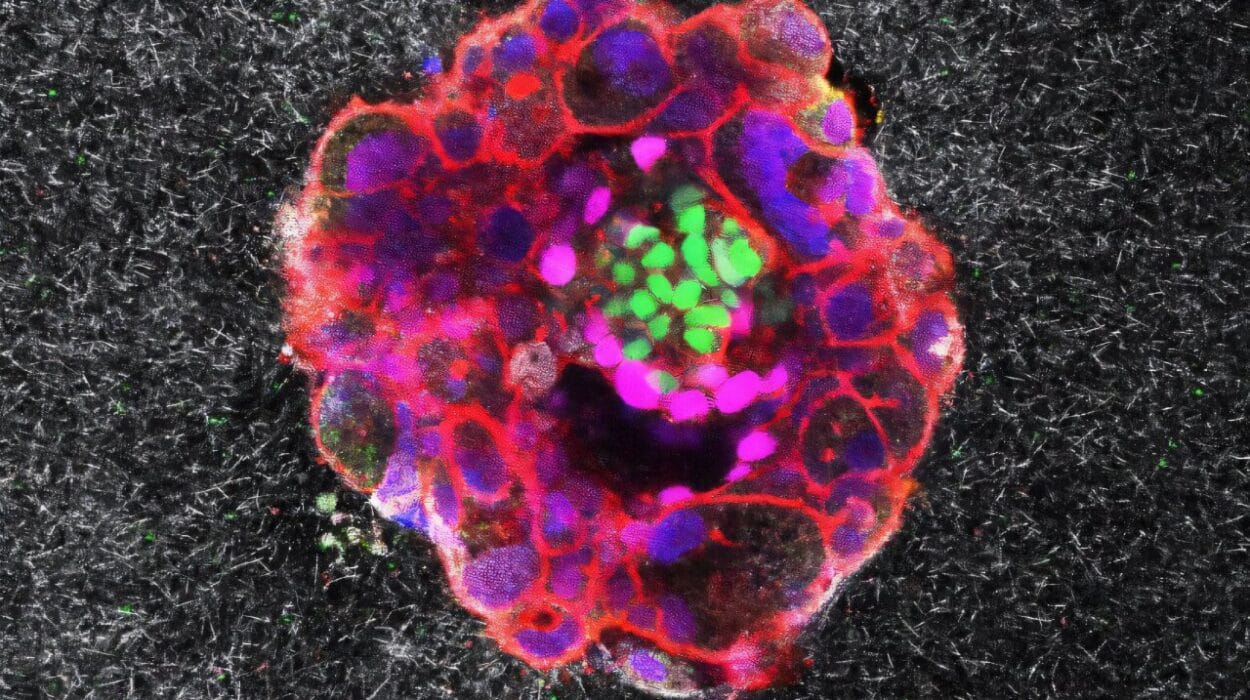

The discovery of DNA’s structure in 1953 by James Watson and Francis Crick (with crucial contributions from Rosalind Franklin) revealed the molecule of inheritance. DNA was the instruction manual for life, written in a code of four chemical letters.

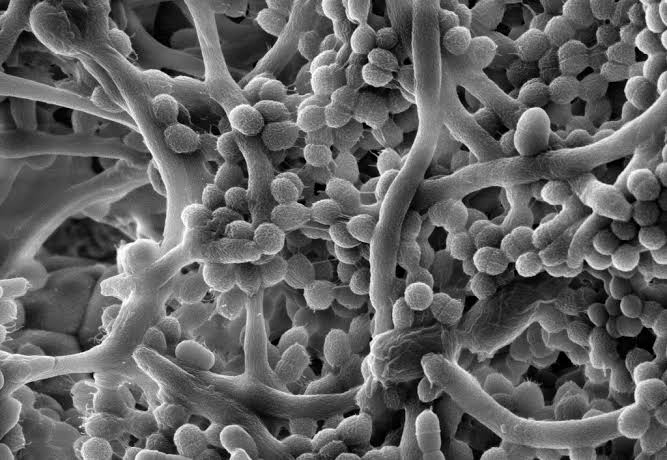

Suddenly, evolution could be traced at the molecular level. Genes could be compared between species. Mutations could be identified. Common ancestry could be measured in shared genetic sequences.

In the decades that followed, the Human Genome Project, CRISPR gene editing, and bioinformatics transformed evolutionary biology into a molecular science. Entire evolutionary trees could be built not from bones or beaks, but from base pairs.

Evolution was no longer just a theory inferred from fossils and patterns. It was a testable, trackable, observable process written into the very essence of life.

Challenges, Controversies, and the Persistence of Misunderstanding

Despite its overwhelming evidence, evolutionary theory has always faced resistance—often cultural rather than scientific. Some religious groups reject evolution in favor of creationist beliefs. Others seek to replace it with so-called “intelligent design,” a rebranding of the old argument from design.

But science is not shaped by popularity. It is shaped by evidence. And the evidence for evolution is overwhelming—from the fossil record to comparative anatomy, from embryology to molecular biology.

Even so, evolutionary biology continues to evolve. Debates rage over the speed and mode of evolution, the role of genetic drift versus natural selection, the origin of consciousness, the power of epigenetics, and the emergence of complex traits.

Science thrives on such debates. They do not undermine evolution; they refine it.

Evolution as a Lens on Life

Today, evolutionary theory is not confined to dusty fossils or jungle expeditions. It informs medicine, agriculture, conservation, psychology, and even computer science.

Understanding the evolution of viruses helps us fight pandemics. Tracing antibiotic resistance saves lives. Modeling human behavior through evolutionary psychology offers insights into cooperation, competition, and morality.

Evolution explains why we suffer from back pain (we weren’t originally bipedal), why we crave sugar (once scarce), and why our immune systems are so complex (arms races with microbes). It reveals that life is not a ladder but a branching tree, with each species a twig connected by common roots.

Perhaps most profoundly, evolution tells us that we are not separate from the natural world. We are not fallen angels. We are risen apes. And in that rising, there is wonder.

The Ongoing Journey of Discovery

A “brief” history of evolutionary thought spans thousands of years and touches every branch of science. It is the story of how humans moved from myth to mechanism, from static belief to dynamic understanding.

And yet, the journey is not over.

Every fossil unearthed, every genome sequenced, every newly discovered species adds a verse to this ongoing song. Evolutionary thought continues to grow—more sophisticated, more humble, more attuned to the complexity of life.

In the end, to study evolution is not merely to study change. It is to study ourselves, to glimpse the improbable chain of events that led from stardust to consciousness, from single cells to symphonies.

We are evolution thinking about itself. And that may be the greatest transformation of all.