In the quiet suburb of Frederiksberg, beneath the old greenhouses on Rolighedsvej, a pair of dusty bottles sat hidden for more than a century. They were unremarkable at first glance—small, white-powdered containers tucked away in a moving box. Yet inside them lay a story that bridges the everyday act of buttering bread with the sweeping history of industrial food science.

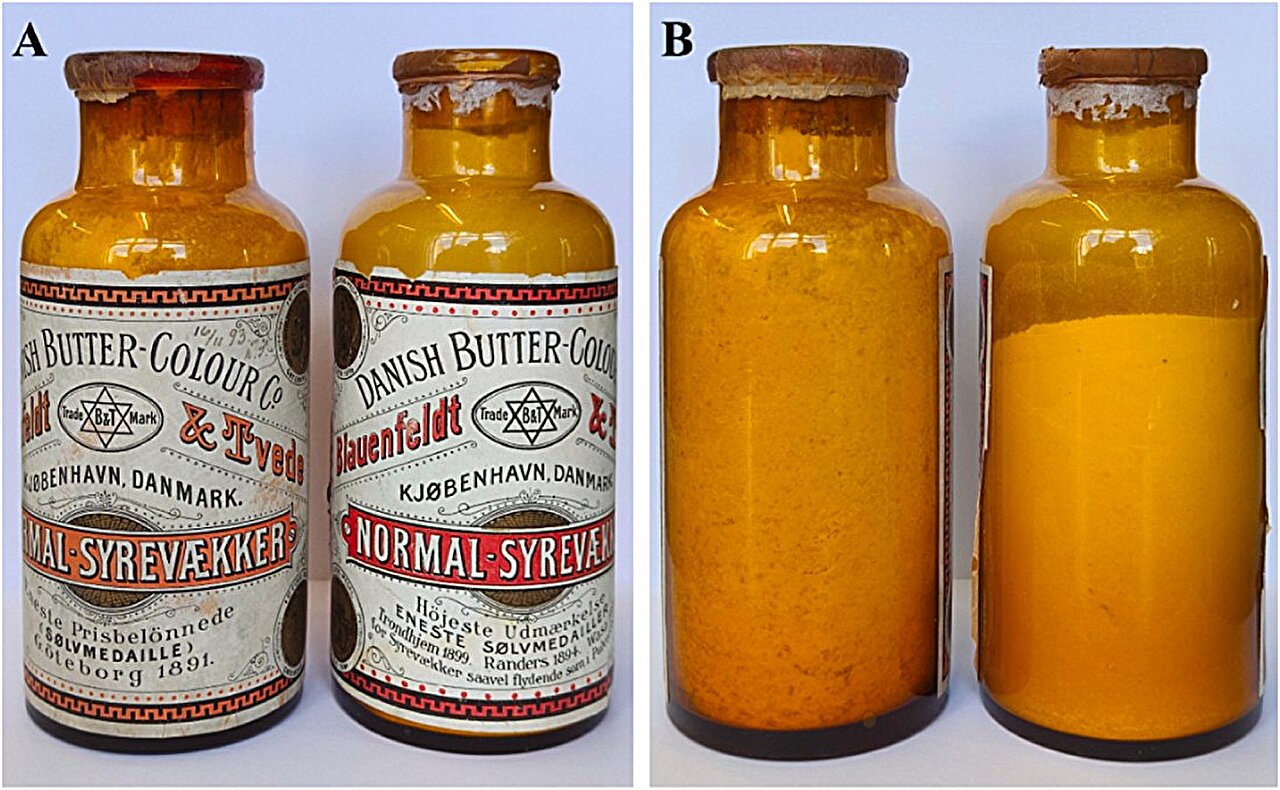

When researchers from the University of Copenhagen stumbled across these bottles, they could not have imagined the treasure within. The labels revealed they contained lactic acid bacterial cultures from the late 1800s. These cultures, long thought lost to time, were once essential tools for transforming Denmark into a global powerhouse of butter production.

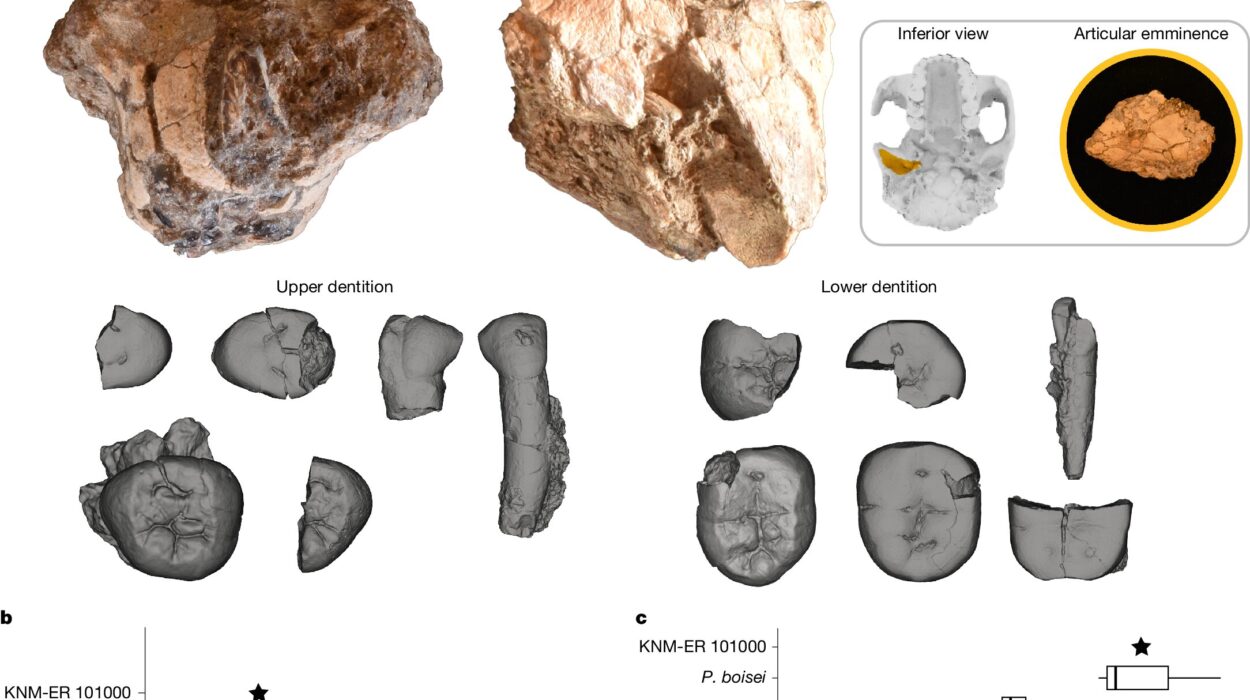

With modern DNA sequencing technology, scientists carefully analyzed the bottles’ contents. What they found was both surprising and deeply illuminating: fragments of life that had shaped Denmark’s agricultural and industrial story, preserved for 130 years.

Lactic Acid Bacteria: Nature’s Tiny Alchemists

To understand why these bottles matter, we must return to the world of the late 19th century. For thousands of years, humans relied on natural fermentation to preserve food. Lactic acid bacteria—those microscopic workers invisible to the naked eye—were central to this process. By producing acid, they made milk sour, flavored butter and cheese, and crucially, prevented dangerous bacteria from taking over.

Denmark was among the first countries to recognize the power of these bacteria not just as a folk tradition, but as a scientific tool. Combined with the introduction of pasteurization—Louis Pasteur’s great innovation to kill harmful microbes—lactic acid bacteria provided a way to produce food that was safer, tastier, and consistent.

The dusty bottles in Frederiksberg contained precisely these starter cultures: powdered bacteria that dairies once added to milk after pasteurization. They were the invisible guardians of Denmark’s butter, ensuring that it not only stayed fresh but also carried the unmistakable flavor that would soon delight foreign markets.

A Window into 19th-Century Dairies

Peering into these bottles with advanced DNA analysis was like time-traveling into the dairies of 1890s Denmark. The researchers identified Lactococcus cremoris, a lactic acid bacterium still widely used today. It is a master at acidifying milk and carried the genetic blueprint for producing diacetyl—the molecule responsible for butter’s rich, golden aroma.

This discovery was both expected and extraordinary. It showed that even 130 years ago, Danish dairies had isolated and cultivated the very microbes that remain essential to modern dairy production. The continuity across generations speaks to the enduring importance of these humble organisms.

But the bottles also told a less polished story. Alongside the helpful microbes, researchers found DNA from Cutibacterium acnes, the same bacterium responsible for acne on human skin. Its hardy cell walls had preserved its DNA remarkably well across the decades. More troubling still, traces of potentially pathogenic bacteria—Staphylococcus aureus and Vibrio furnissii—were present.

These findings are not simply curiosities. They are reminders of the very real challenges of hygiene in a time before modern sanitary standards. Dairies of the 19th century were innovative, but they were not yet sterile environments. The butter that fed England’s growing industrial cities carried with it the invisible fingerprints of a world still learning to manage microbes.

Denmark’s Butter Revolution

By the late 1800s, Denmark was at the heart of a global transformation in food. Small family farms had long churned butter in kitchens and barns, each with its own unique flavor depending on the local microbes. But as Denmark turned its gaze outward—especially toward the lucrative English market—consistency became essential.

England wanted butter that always tasted the same, regardless of whether it came from Jutland, Funen, or Zealand. The answer was starter cultures. By standardizing the bacteria added to milk after pasteurization, Denmark ensured that its butter would be reliable, safe, and delicious.

The bottles from Frederiksberg are artifacts of this turning point. They represent the moment when butter ceased to be only a farmhouse craft and became an industrial product. This shift required science, technology, and bold collaboration between researchers, farmers, and entrepreneurs.

The Human Story Behind the Science

What makes this discovery so powerful is not only the science but the humanity woven into it. One can imagine the dairymen of the 1890s, measuring out spoonfuls of powdered culture, perhaps unaware that they were part of a global transformation. One can picture the scientists of the Agricultural College in Frederiksberg carefully bottling the cultures, confident that they held the key to Denmark’s economic future.

These bottles, forgotten in a basement, are more than relics. They are a reminder of the people who lived in a time of transition, balancing tradition with innovation. For every sterile laboratory, there was still a farmhouse kitchen with a jar of sour milk by the stove. For every bacterium cultivated to perfection, there were countless invisible companions hitching a ride into the butter churn.

Butter as a National Treasure

At the dawn of the 20th century, Danish butter became more than food—it became a symbol of national success. Exports soared, and Denmark built a reputation for quality that still lingers in its food culture today. Behind that success were the starter cultures: the invisible microbes that guaranteed every pat of butter tasted as it should.

Companies like Christian Hansen and Blauenfeldt & Tvede grew out of this period, transforming from small enterprises into global players. Their work laid the foundation for the modern food industry, where microbes are carefully selected, cultivated, and sold around the world.

The forgotten bottles now remind us that none of this happened overnight. It was the result of years of trial, error, collaboration, and scientific daring. Each butter shipment to England carried within it not only calories and flavor, but also the story of Denmark’s determination to innovate.

Echoes of the Past in Modern Science

For the University of Copenhagen researchers, analyzing the bottles was not just a scientific exercise—it was a dialogue with history. To hold in their hands the same bacteria that had flavored butter more than a century ago was to feel a direct connection across time.

The discovery also underscores how modern science can illuminate the past. Advanced DNA sequencing, a technology unthinkable in the 1890s, gave voice to microbes that would otherwise remain silent. It is a testament to how far microbiology has come, and yet how deeply it remains tied to the same questions: How do microbes shape our food, our health, and our world?

Lessons for Today

The bottles’ contents are not only of historical interest. They serve as reminders of the delicate balance between helpful and harmful bacteria. They show us that food safety—a concept we take for granted today—was hard-won through decades of scientific progress.

They also remind us that the flavors we cherish are not accidents. The taste of butter, the tang of yogurt, the sharpness of cheese—all are gifts from microbes carefully cultivated by humans. Behind every bite of dairy lies a partnership between people and bacteria that has endured across centuries.

A Legacy Preserved

In the end, the forgotten bottles from Frederiksberg are more than scientific samples. They are fragments of a larger story: of Denmark’s rise as a global food exporter, of the marriage between tradition and innovation, and of the microbes that made it all possible.

They teach us that history is not only written in books but preserved in unlikely places—sometimes even in a dusty basement. And they remind us that the smallest forms of life can carry the weight of a nation’s story, shaping what we eat, how we live, and how we connect across time.

The butter that once spread across English bread carried with it the invisible labor of lactic acid bacteria. Today, thanks to two forgotten bottles, we can once again glimpse the remarkable journey of those microbes—and the people who trusted them to help build Denmark’s butter adventure.

More information: Pablo Atienza López et al, Metagenomic analysis of 130 years old Danish starter culture material including sequence analysis of the genome of a Lactococcus cremoris starter, International Dairy Journal (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2025.106258