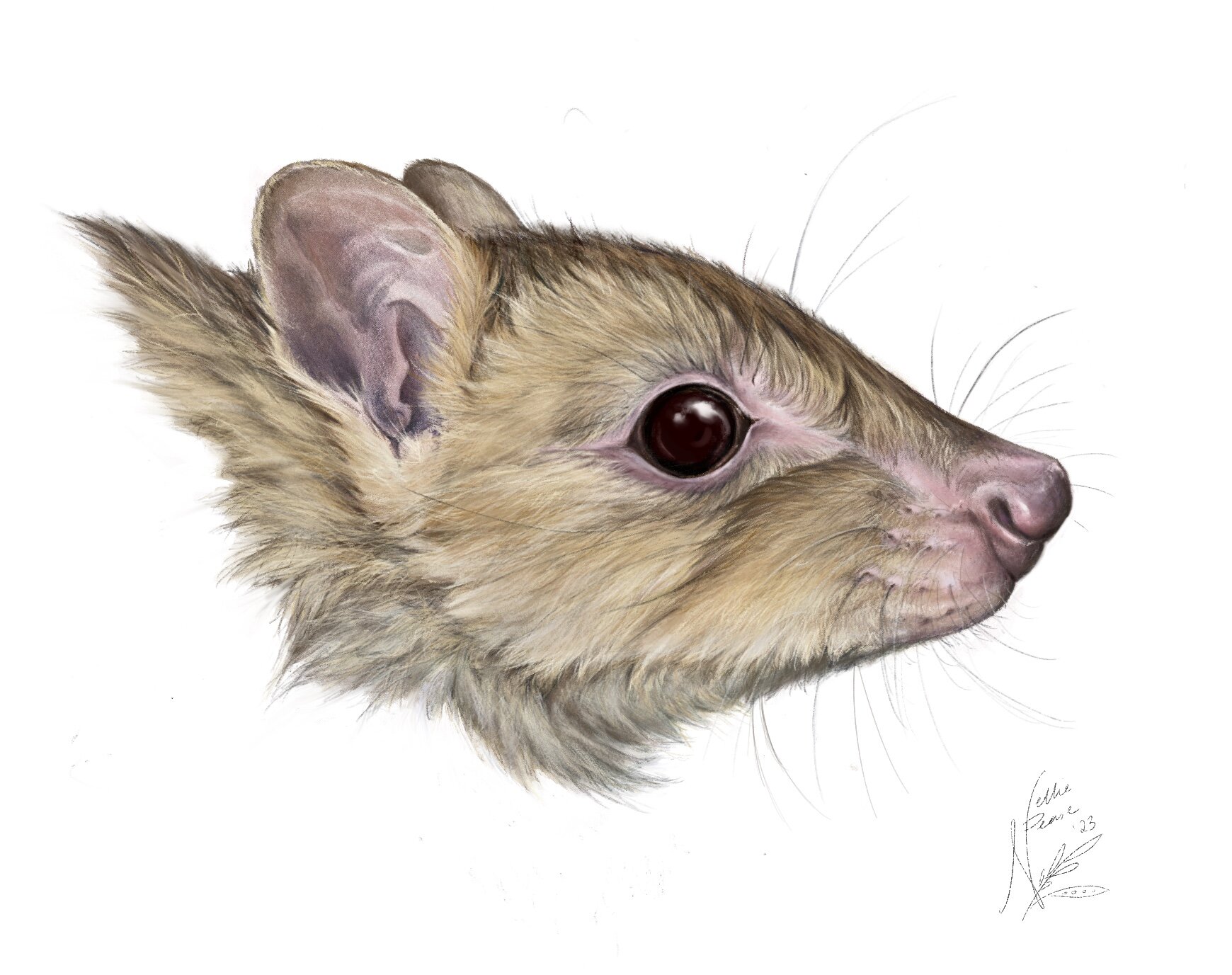

In the heart of Australia’s dry landscapes, hidden within the limestone caves of the Nullarbor and the scrublands of the southwest, scientists uncovered a remarkable story preserved in fragments of bone. These fossils—quiet, dusty remnants of a vanished life—belonged to a creature we never knew existed, a small marsupial closely related to the kangaroo.

The discovery is bittersweet. The species, now named Bettongia haoucharae, was entirely new to science, a native bushland bettong that once hopped across Australia’s landscapes. Yet, even as we learn its name, we are confronted with the likelihood that it is already extinct.

This paradox—finding new life only in death—speaks volumes about the fragile balance of Australia’s ecosystems and the urgency of conservation in a country where unique animals have disappeared faster than almost anywhere else on Earth.

Meeting the Woylie and Its Kin

The new species belongs to a family of marsupials known as bettongs, small nocturnal kangaroo-relatives that once roamed widely across Australia. Among them, the woylie, or brush-tailed bettong (Bettongia penicillata), stands out as an ecological engineer.

Woylies live for mushrooms. In their endless quest for underground fungi, they dig tirelessly through soil, turning over several tons of earth each year. This activity aerates the soil, spreads fungal spores, and enriches ecosystems—much like earthworms in other parts of the world. The survival of forests and shrublands is quietly intertwined with the survival of these humble marsupials.

And yet, despite their importance, woylies are teetering on the edge. Once abundant, they are now critically endangered, their numbers slashed by habitat loss, predation by introduced foxes and cats, and disease. Conservationists have spent decades translocating woylies to safer habitats, battling to ensure that this little ecosystem engineer does not vanish.

A Discovery From the Shadows

The breakthrough came through the work of researchers at Curtin University, the Western Australian Museum, and Murdoch University. By carefully analyzing fossil remains—skulls and bones long hidden in caves—they discovered not only a brand-new species, Bettongia haoucharae, but also two previously unrecognized subspecies of the living woylie.

For scientists, each measurement of a fossil skull was like piecing together a forgotten biography. These bones told stories of diversity that had been overlooked, revealing that what we once thought of as a single species was in fact more varied and complex.

Ph.D. student and lead author Jake Newman-Martin explained that these revelations are not just academic curiosities. Understanding the diversity of woylies has direct consequences for conservation. If we recognize distinct subspecies, then breeding and relocation programs can be tailored to preserve their genetic integrity, rather than accidentally erasing it through mismanaged mixing.

It is a reminder that the finer details of science—the measurements, the classifications, the names—can mean the difference between survival and decline.

The Bitter Taste of Extinction

And yet, the heart of this discovery is tinged with sorrow. Bettongia haoucharae, the new Nullarbor species, no longer bounds across the desert. Its story ended before we could fully know it.

This is a recurring theme in Australian natural history. Species disappear quietly, slipping out of existence long before their names are written. Fossils often serve as our only introduction, whispering of animals that once carried out vital roles in ecosystems now altered beyond recognition.

The tragedy is not only the loss of the species itself, but the loss of everything it contributed. What fungi depended on this bettong to spread their spores? What plants relied on those fungi for survival? How did its absence shift the balance of life in the desert? These questions linger unanswered, and with them comes the haunting thought of what else we may already have lost.

Indigenous Names, Shared Knowledge

While the scientific name Bettongia haoucharae is already recorded in the literature, the researchers are careful to acknowledge that the woylie is deeply rooted in Indigenous culture. The very word “woylie” comes from the Noongar language of southwest Australia.

Future naming will involve collaboration with Indigenous communities, ensuring that the species is honored not only in Latin taxonomy but also within the traditions of those who have lived alongside these animals for tens of thousands of years. This recognition is more than symbolic. Indigenous ecological knowledge, built over millennia, offers perspectives on ecosystems that Western science alone cannot provide. By weaving these understandings together, conservation efforts become richer, more respectful, and more effective.

Why This Discovery Matters

It might be tempting to dismiss the finding of an extinct species as irrelevant—a scientific curiosity, too late to matter. But this research carries deep significance for the living. By carefully examining the past, we sharpen our tools for protecting the present.

The splitting of woylies into two distinct subspecies means conservation programs must adapt. Translocations—the practice of moving animals to safer habitats—need to account for genetic differences. Breeding programs must preserve diversity, not inadvertently dilute it. The work also demonstrates the power of combining fossil studies with modern genetic tools, offering a roadmap for protecting other threatened species before it is too late.

Above all, this discovery is a wake-up call. If we are losing species before we even know their names, how many more are slipping through the cracks of our awareness? The urgency of conservation becomes undeniable.

The Fragile Future of Australia’s Marsupials

Australia is a land of marvels—kangaroos that bound across plains, wombats that burrow underground, platypuses that defy imagination. But it is also a land of loss. Since European colonization, more than thirty species of mammals have gone extinct, giving Australia the highest mammalian extinction rate in the world.

The woylie clings to survival, its fate uncertain but not yet sealed. The story of Bettongia haoucharae is a stark reminder that extinction is not a distant threat but a present reality. Every conservation effort—every predator control program, every habitat restoration, every carefully managed translocation—becomes a lifeline.

If we succeed, woylies may continue to dig, to spread fungi, to engineer ecosystems for generations to come. If we fail, their story will join that of their vanished relative, a name in a paper, a ghost in the fossil record.

A Call to Wonder and Responsibility

In the end, the discovery of Bettongia haoucharae is not just about a lost marsupial. It is about how we see ourselves in relation to the natural world. Each species, no matter how small, is a thread in the fabric of life. When one is cut, the whole cloth weakens.

There is wonder in the fact that such discoveries are still possible, that the earth holds secrets waiting patiently in caves and soils for us to find. But there is also responsibility. To uncover a species only to declare it extinct should stir us—not only to sadness, but to action.

The woylie’s story is still being written. With care, with science, and with respect for the deep knowledge of Indigenous custodians, we may yet keep it alive. And in doing so, we honor not only the living but also the silent, vanished relatives like Bettongia haoucharae that remind us what is at stake.

More information: A taxonomic revision of the Bettongia penicillata (Diprotodontia: Potoroidae) species complex and description of the subfossil species Bettongia haoucharae sp. nov., Zootaxa (2025). DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.5690.1.1