When most of us think about pollination, images of bees buzzing between flowers, butterflies drifting from bloom to bloom, or even flies landing on blossoms come to mind. These creatures are rightly celebrated as the great pollinators of our modern world. Yet hidden in the pages of Earth’s ancient history lies a different truth: pollination was once more diverse, and insects we rarely associate with flowers today—true bugs—may have once played a crucial role.

A recent study published in Scientific Reports unveils this forgotten chapter. By examining a tiny creature preserved in nearly 100-million-year-old Burmese amber, Hungarian researchers have revealed evidence that bugs, too, once helped carry pollen and keep ecosystems flourishing. This discovery not only enriches our understanding of the deep past but also reminds us how fragile, dynamic, and interconnected life on Earth truly is.

Amber: Time’s Perfect Memory

Amber, fossilized tree resin, is more than a gemstone admired for its warm glow. It is nature’s time capsule. When sticky resin dripped down ancient trees and trapped insects, plants, or small animals, it preserved them with breathtaking detail. Millions of years later, these inclusions allow scientists to glimpse ecosystems long vanished.

Among the most important amber deposits is Burmese amber, also called burmite. Formed around 99 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous, burmite originated in the equatorial forests of the West Burma terrane, a landmass that had already separated from the supercontinent Gondwana. Isolated for millions of years, this environment gave rise to a unique menagerie of creatures—some familiar, many strange, and all preserved in exquisite detail.

To peer into a piece of amber is to look directly into the Cretaceous, when dinosaurs still roamed the Earth and flowering plants were just beginning to spread across continents.

A Bug Unlike Any Other

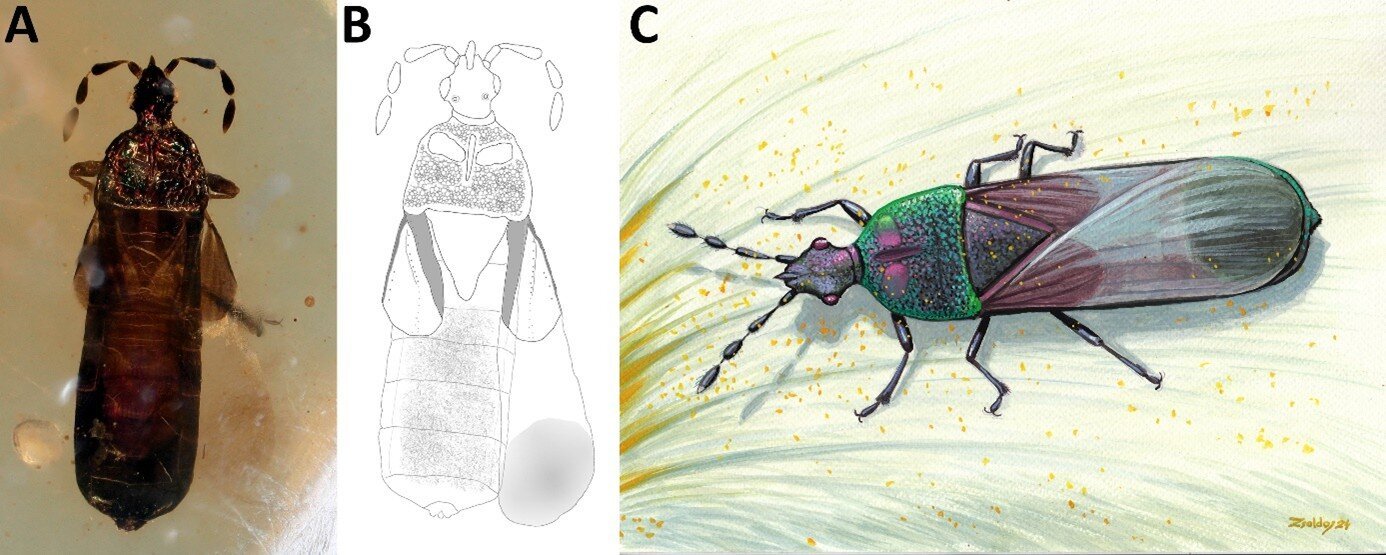

Within one such amber specimen, researchers Péter Kóbor of the Plant Protection Institute (HUN-REN ATK) and Márton Szabó of the Hungarian Natural History Museum and Eötvös Loránd University made a remarkable discovery. Encased in golden resin lay a flat bug belonging to the family Aradidae, specifically the subfamily Prosympiestinae.

This insect was something special. Named Shaykayatcoris michalskii, it represents the first known member of its subfamily in Burmese amber. What set it apart, however, was not just its rarity but its appearance: unlike the dull, cryptic forms of its relatives, this ancient bug shimmered with iridescent colors. Its exoskeleton reflected light in hues never before seen in its family, an almost jewel-like display frozen for eternity.

Flat bugs today are hardly flamboyant. They live hidden under tree bark, feeding on fungal threads, with bodies flattened to slip into narrow spaces. But Shaykayatcoris told a different story. Its body was more cylindrical, its habitat closer to leaf litter and fallen logs, and its iridescence suggested a surprising connection to flowers.

The Secret of Iridescence

Why would a bug glow with shimmering colors in a world where most of its kind were drab? Iridescence in insects can serve multiple purposes. In some species, it functions as a warning—a way of saying “don’t touch” to predators. Bright reds and metallic flashes can signal toxicity. But in Shaykayatcoris, whose base color was brown, this explanation is unlikely.

Instead, the researchers propose a more intriguing role: camouflage. In a dappled floral environment, shifting colors could have helped the bug blend into blossoms and petals, masking its presence from predators. If true, this would mean the insect was not lurking in shadows like its modern relatives but moving openly among flowers.

And the evidence for this goes beyond its shimmering body.

Traces of Pollen in Stone

Alongside the insect’s preserved form were plant fragments and, most tellingly, a halo of pollen grains. Some were even attached to the bug’s own body. The image is easy to imagine: tens of millions of years ago, Shaykayatcoris landed on a flower, brushing against its pollen. Then, by chance, resin trapped the moment forever.

This frozen snapshot strongly suggests that the bug was indeed a flower visitor, and therefore, a pollinator. It may have carried pollen from one bloom to another, unwittingly aiding the reproductive dance of plants just as bees do today.

For scientists, this is a breakthrough. It confirms that the role of bugs in pollination, now nearly forgotten, was once more prominent in Earth’s history.

A Lost Role in Nature’s Web

Today, true bugs rarely play a role in pollination. Over evolutionary time, they were overshadowed by more specialized pollinators—bees with their efficient pollen-collecting hairs, butterflies with their long proboscises, flies with their adaptability. These groups filled the floral niche more effectively, gradually pushing bugs out.

But the discovery of Shaykayatcoris michalskii rewrites that story. It shows that in earlier stages of flowering plant evolution, bugs may have been significant allies in spreading pollen. The ecosystems of the Cretaceous were not yet dominated by bees. Instead, a variety of insects, including true bugs, contributed to the survival and spread of early flowers.

This revelation underscores a broader truth: ecosystems are dynamic. Roles shift, species rise and fall, and what seems marginal today may once have been central.

Lessons for Today’s World

At first glance, the fate of a shimmering bug from 99 million years ago may seem like a curiosity, a detail in the fossil record. Yet its story resonates deeply with the present. Today, pollinators face a crisis. Bees, butterflies, and other key species are declining due to habitat loss, pesticides, climate change, and disease. This threatens not only biodiversity but also human food security.

The ancient bug reminds us of two things. First, nature has always been in flux. Just as bugs once gave way to bees, so too might pollinator communities shift in the future. Second, however, is the warning: such shifts can have far-reaching consequences. The disappearance of one group may leave ecosystems vulnerable, especially if replacements cannot fill their role quickly enough.

By studying how pollination evolved in the past, scientists gain insight into resilience and adaptation. Ancient amber does not just tell us what once was; it helps us prepare for what may come.

A Jewel of Deep Time

The discovery of Shaykayatcoris michalskii is more than a scientific report. It is a window into a vanished world—a moment when the air was filled with the scents of new flowers, when strange insects glittered among the petals, and when life was experimenting with new partnerships.

That this story comes to us through amber is poetic. Resin that once flowed down a tree trunk has outlasted continents, oceans, and species, carrying forward the memory of a tiny creature and its iridescent secret. Today, we hold it up to the light and, for a moment, glimpse the Cretaceous.

And in that glimpse, we see not just a bug but a message: pollination has always been a delicate, shifting collaboration, one that sustains the planet and all who depend on it. Protecting it now is part of honoring that ancient, unbroken chain of life.

More information: Péter Kóbor et al, A new fossil plesiomorphic flat bug (Aradidae) suggests widespread flower visiting in Heteroptera during the Mesozoic, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-15559-8