It began with a quiet contradiction buried in the ground of North Dakota. Paleontologists working in sediments shaped by ancient rivers uncovered a large, worn tooth. At first glance, it seemed unmistakable. The tooth belonged to a mosasaur, a giant marine reptile that lived more than 66 million years ago and was long believed to roam only the open seas. Yet here it was, found far from any ancient shoreline, resting in a fluvial deposit alongside a tooth from Tyrannosaurus rex and the jawbone of a crocodylian.

The land around the discovery site was already famous for its dinosaur remains, especially those of the duck-billed Edmontosaurus. Still, this tooth did not fit the story anyone thought they knew. Land-dwelling dinosaurs, river-dwelling crocodiles, and a massive marine predator all preserved together posed a question that refused to go away. How did a mosasaur tooth end up in a river?

That question would soon open a window into the final chapter of mosasaur history, revealing animals far more adaptable than previously imagined.

Following the Chemical Echoes of an Ancient Life

To answer the mystery, an international team of researchers from the United States, Sweden, and the Netherlands turned to the chemistry locked inside the tooth itself. The study, led from Uppsala University and published in BMC Zoology, relied on isotope analyses of the tooth enamel, a method that allows scientists to reconstruct aspects of an animal’s environment and diet long after it has vanished.

The mosasaur tooth, the Tyrannosaurus rex tooth, and the crocodylian jawbone were all roughly the same age, about 66 million years old. This allowed the researchers to compare their chemical signatures directly. The analyses were carried out at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, focusing on isotopes of oxygen, strontium, and carbon.

These isotopes act like subtle fingerprints. They record where an animal lived and what kind of food it consumed. In this case, they would determine whether the mosasaur truly belonged in a river or whether its tooth had somehow been transported there after death.

A Freshwater Signal in a Marine Predator

The results were striking. The mosasaur tooth contained more of the lighter oxygen isotope, ¹⁶O, than is typically found in marine mosasaurs. This pattern is characteristic of freshwater environments. The ratios between different strontium isotopes told the same story, pointing away from salty oceans and toward rivers.

Carbon isotopes added another layer of insight. As one of the study’s corresponding authors, Melanie During, explained, “Carbon isotopes in teeth generally reflect what the animal ate. Many mosasaurs have low ¹³C values because they dive deep. The mosasaur tooth found with the T. rex tooth, on the other hand, has a higher ¹³C value than all known mosasaurs, dinosaurs and crocodiles, suggesting that it did not dive deep and may sometimes have fed on drowned dinosaurs.”

This was no wandering tooth carried inland by chance. The chemical evidence suggested that this mosasaur lived in freshwater, hunted near the surface, and occupied an environment previously thought to be beyond the reach of such enormous marine reptiles.

A Pattern That Repeats in the Past

To make sure this was not a one-off case, the researchers examined two additional mosasaur teeth found at nearby sites in North Dakota. These sites were slightly older but still close in time to the extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous.

The pattern held. These teeth also showed freshwater signatures.

“The isotope signatures indicated that this mosasaur had inhabited this freshwater riverine environment. When we looked at two additional mosasaur teeth found at nearby, slightly older, sites in North Dakota, we saw similar freshwater signatures. These analyses show that mosasaurs lived in riverine environments in the final million years before going extinct,” said During.

Together, these findings painted a picture of mosasaurs not as strictly ocean-bound giants, but as animals capable of exploiting new habitats as their world changed around them.

When an Inland Sea Began to Fade

The discovery does more than rewrite the lifestyle of a single animal. It sheds light on a dramatic transformation in Earth’s geography near the end of the age of dinosaurs. At that time, much of central North America was submerged beneath the Western Interior Seaway, an inland sea that stretched from north to south and split the continent in two.

Over time, increasing influxes of freshwater altered this vast body of water. What had once been a salty sea gradually became brackish and then mostly freshwater, in a process compared by the researchers to conditions seen today in the Gulf of Bothnia.

This transformation likely created a halocline, a layered water column in which lighter freshwater rested atop heavier saltwater. Isotope analyses supported this idea and helped explain how different animals responded to the changing conditions.

Living Between Two Worlds

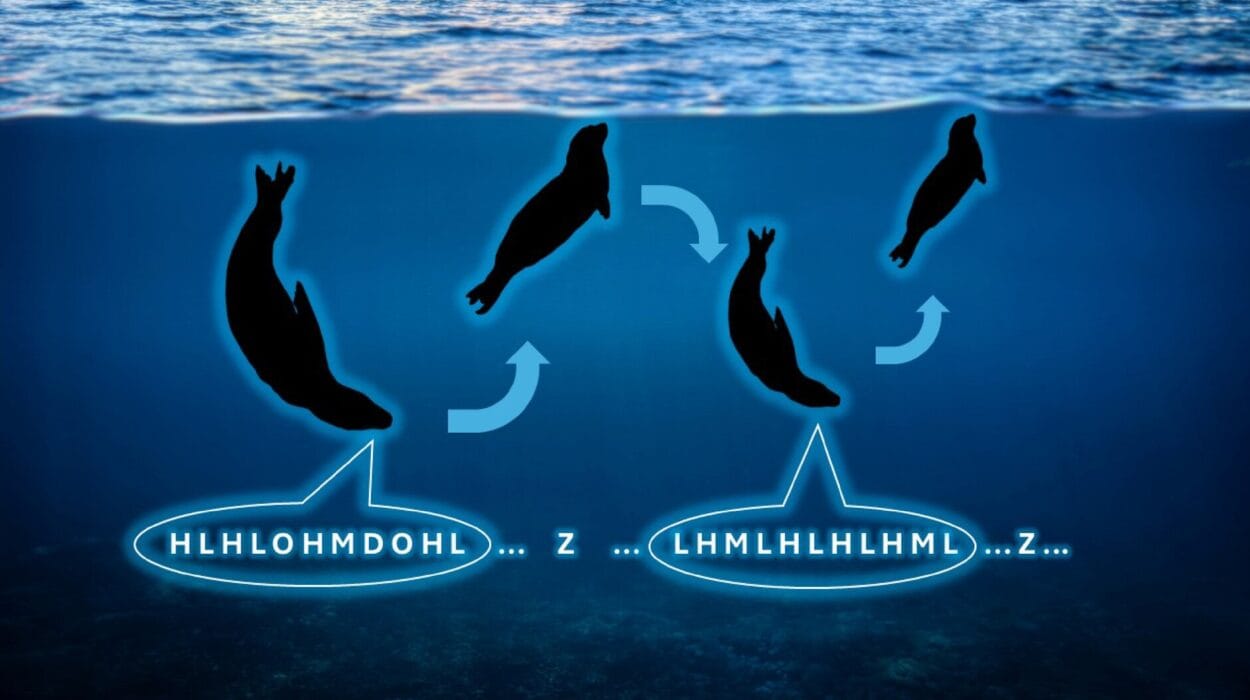

To test their interpretation, the researchers compared the mosasaur teeth with fossils from other marine animals. The contrast was clear. Gill-breathing animals showed isotope signatures consistent with brackish or salty water. Lung-breathing animals did not.

“For comparison with the mosasaur teeth, we also measured fossils from other marine animals and found a clear difference. All gill-breathing animals had isotope signatures linking them to brackish or salty water, while all lung-breathing animals lacked such signatures. This shows that mosasaurs, which needed to come to the surface to breathe, inhabited the upper freshwater layer and not the lower layer where the water was more saline,” said Per Ahlberg, a co-author of the study and promotor of Dr. During.

This insight suggests that mosasaurs adapted their behavior to the layered waters of a changing seaway, occupying the freshwater surface where breathing was easier and prey may have been plentiful.

Adapting at the Edge of Extinction

The researchers argue that the mosasaur teeth clearly came from animals adapted to these shifting environments. Such ecological flexibility is not unheard of among large predators, particularly when moving from marine habitats into freshwater.

“Unlike the complex adaptation required to move from freshwater to marine habitats, the reverse adaptation is generally simpler,” said During.

This perspective places mosasaurs within a broader pattern of evolutionary change, where animals respond to environmental pressure not by retreating, but by experimenting with new ways of living.

A Giant in the River

The tooth itself tells another astonishing story. Its size suggests an animal that could reach up to 11 meters in length, roughly the size of a bus. This estimate is supported by a small number of mosasaur bones found earlier at a nearby site in North Dakota.

The tooth belonged to a prognathodontine mosasaur, closely related to the genus Prognathodon, though its exact genus cannot be determined with certainty. These mosasaurs were known for their bulky heads, powerful jaws, and robust teeth. They were opportunistic predators, capable of taking on large prey.

“The size means that the animal would rival the largest killer whales, making it an extraordinary predator to encounter in riverine environments not previously associated with such giant marine reptiles,” said Ahlberg.

Imagining such a creature gliding through ancient rivers, sharing the landscape with tyrannosaurs and crocodiles, reshapes our understanding of these ecosystems entirely.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research changes how we see mosasaurs and the world they inhabited. It shows that in the final million years before their extinction, some mosasaurs were not confined to shrinking seas. Instead, they adapted to rivers and freshwater systems as the Western Interior Seaway transformed around them.

The study highlights the power of isotope analysis to uncover hidden chapters of natural history and reminds us that extinction often comes after a period of intense adaptation and experimentation. Mosasaurs were not static relics waiting for their end. They were dynamic, flexible predators responding to a rapidly changing environment.

By revealing mosasaurs as river-dwelling giants at the twilight of their existence, this research adds depth and complexity to the story of life before the mass extinction 66 million years ago. It reminds us that even the most iconic creatures can surprise us, and that the past still holds secrets waiting quietly in the ground, written in the chemistry of a single tooth.

More information: Melanie During , “King of the Riverside”, a multi-proxy approach offers a new perspective on mosasaurs before their extinction, BMC Zoology (2025). DOI: 10.1186/s40850-025-00246-y. www.biomedcentral.com/articles … 6/s40850-025-00246-y