Beneath our feet lies an ancient record—layer upon layer of Earth’s memory, pressed into stone, hidden in sediment, or entombed in blackened tar. Some of these buried treasures whisper secrets of life long extinct, etched into skeletal imprints left by ancient beasts and prehistoric plants. These are fossils: nature’s own museum, silent but eloquent. Others lie deeper still, thick with energy and fire, forged in time’s darkest furnace. These are fossil fuels—coal, oil, and natural gas—burning relics of a once-living world, igniting not only machines but debates that now shape humanity’s future.

Both fossils and fossil fuels share a common origin in life that thrived long before the dawn of humankind. Yet they are not the same. One tells us who we were; the other powers who we are. They diverge in form, in function, in consequence—and most critically, in the choices they force us to make.

To truly grasp their differences, one must first journey into the ancient Earth, to a world that predates memory, where life rose, perished, and was preserved or transformed under nature’s pressure. It is a journey through billions of years, connecting evolution to combustion, extinction to extraction.

The Ghosts in Stone

Fossils are the mineralized remains or impressions of organisms that lived long ago. They can be as grand as the towering skeleton of a Tyrannosaurus rex or as subtle as the ripple of a fern’s frond imprinted on rock. Fossils are nature’s time capsules, preserving moments of life that once flourished in oceans, forests, and swamps—creatures that lived, died, and then, through an almost miraculous process, resisted decay long enough to become part of the Earth itself.

Contrary to popular belief, fossils are not typically made of the original bone or tissue. Over millennia, organic material is replaced by minerals such as silica or calcite. This process, called permineralization, preserves the shape and structure of the original organism with uncanny precision. Some fossils even retain microscopic features: the scales of a fish, the feathers of a bird, the pollen grains of a forgotten flower.

Fossils can also be mere traces—footprints, burrows, coprolites (fossilized feces), or nests—that tell us how ancient organisms lived. They are the script of evolution, a silent literature detailing mass extinctions, adaptive radiations, and the ceaseless march of life on Earth.

Each fossil is a singular artifact, precious and irreplaceable. They are excavated with reverence, analyzed with awe, and curated in museums where they quietly redefine how we understand ourselves. The discovery of a single fossilized tooth can rewrite evolutionary trees. The imprint of a single feather can prove dinosaurs were not reptiles but the ancestors of birds.

The Flames of Ancient Life

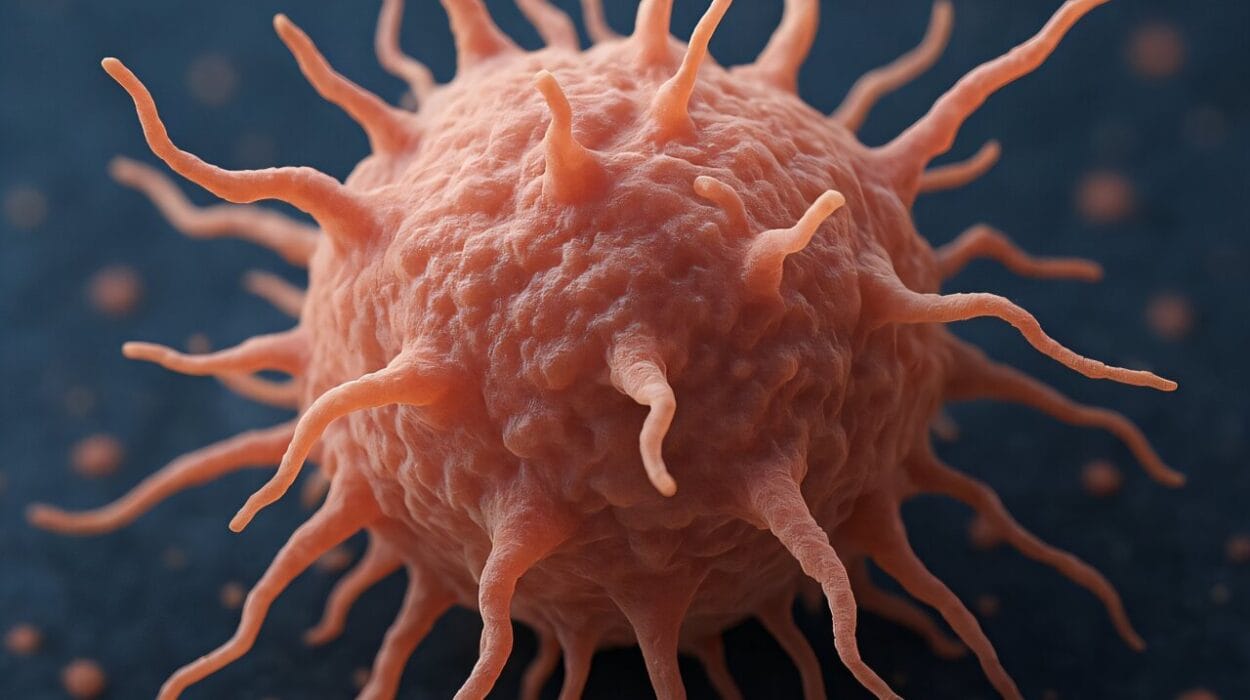

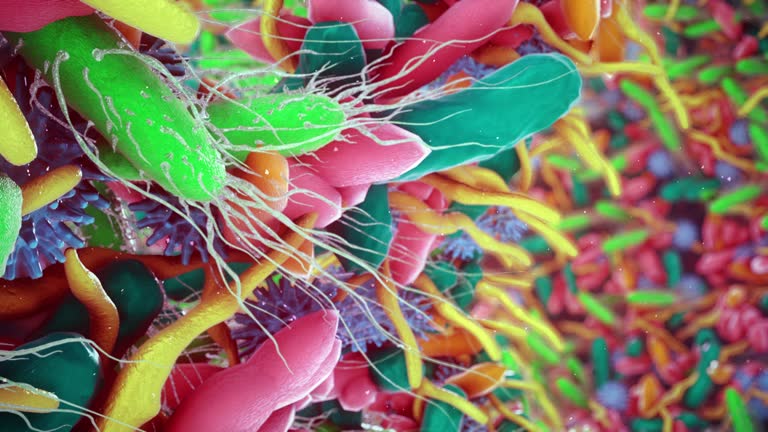

While fossils are monuments to life, fossil fuels are the energy locked within life’s decay. Born of the same distant past, fossil fuels are the compressed and chemically transformed remains of ancient organisms—mostly plants and microorganisms—that died millions to hundreds of millions of years ago. These organisms, buried under sediment and subjected to intense heat and pressure, were not preserved but altered. Their biomass was broken down, their hydrogen and carbon atoms reconfigured into flammable energy sources: coal, oil, and natural gas.

Coal, black and brittle, formed mostly from plant matter—ferns, trees, and mosses that once carpeted prehistoric swamps. Oil and natural gas, on the other hand, owe their existence to the microscopic organisms of ancient seas—plankton, algae, and bacteria that settled to the seafloor and began a transformation no human eye ever witnessed. Over millions of years, under immense geological stress, their chemical signatures morphed into hydrocarbons—molecules rich in stored solar energy.

When we burn fossil fuels, we are not merely igniting a substance—we are unleashing the solar energy captured eons ago by ancient life. We are, in effect, tapping into Earth’s long-lost sunlight. This energy has powered our machines, our cities, our transportation, and our industrial revolutions. It is the cornerstone of modern civilization.

But unlike fossils, which quietly tell stories, fossil fuels shout consequences.

The Cost of Fire

Fossil fuels made the modern world possible. They drove the engines of the Industrial Revolution, powered the spread of human civilization, and lifted billions out of poverty. They are cheap, energy-dense, and relatively easy to transport and store. Without them, the 20th century would have looked very different.

But this prosperity came with a catch—one we ignored for too long.

Burning fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide, methane, and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. These gases trap heat, disrupting Earth’s climate systems and accelerating global warming. We see the results everywhere: melting ice caps, rising seas, longer droughts, stronger hurricanes, displaced populations, and vanishing ecosystems.

Fossil fuels also pollute our air and water. Coal-burning power plants emit mercury, sulfur dioxide, and particulate matter that contribute to respiratory illnesses. Oil spills ravage marine ecosystems. Fracking can contaminate groundwater and cause earthquakes. The economic benefits of fossil fuels are steeped in environmental costs.

Fossils teach us about extinction. Fossil fuels threaten to make us part of the next one.

Time as a Dividing Line

One of the key differences between fossils and fossil fuels is their relationship with time. Fossils preserve it. Fossil fuels consume it.

Fossils are remnants of life that resisted time. Their preservation was accidental, rare, and often miraculous. Every fossil is an exception to the rule of decay. They are the products of delicate balances—conditions that allowed nature to freeze a moment from deep history and deliver it to the future. Fossils tell us that time can be kind, that stories can survive.

Fossil fuels are what happens when time is unforgiving. They are the residue of life that nature forgot to preserve. Where fossils are static, fossil fuels are dynamic—chemical engines of combustion. We extract them, burn them, and convert their potential into motion and heat. But every act of combustion is a one-way ticket. The carbon that was once safely buried is flung back into the atmosphere, changing the planet’s chemistry one ton at a time.

Time shaped both. But how we relate to them determines whether time remains on our side.

Digging Deeper: Extraction and Ethics

Extracting fossils is a scientific endeavor. It involves careful excavation, documentation, and preservation. Paleontologists study rock layers, or strata, to date fossils accurately and understand the environmental context in which ancient organisms lived and died. It is a meticulous process, often requiring years of fieldwork and analysis. Fossils are protected by law in many countries; illegal collection or sale is considered a theft from humanity’s shared heritage.

Fossil fuel extraction, in contrast, is a multibillion-dollar industry. It involves drilling, mining, and hydraulic fracturing—operations that scar landscapes, displace communities, and often damage ecosystems. It is driven by profit, politics, and an insatiable global appetite for energy. Unlike fossils, fossil fuels are not treated as precious relics but as resources to be exploited, often at great environmental and human cost.

This difference speaks volumes about what we value. Fossils are respected for their scientific and cultural worth. Fossil fuels are desired for their immediate utility. One is unearthed to understand; the other, to consume.

Fossils as Teachers

If we are wise, we will listen to what fossils have been trying to tell us. They speak of extinction—not in abstract terms, but in layers of rock filled with vanished creatures. The fossil record contains the evidence of five major mass extinctions, when life on Earth was nearly wiped out. The Permian-Triassic extinction, the most severe, eliminated over 90% of marine species. Its causes were complex but included rapid climate change triggered by massive volcanic eruptions and greenhouse gas emissions.

Sound familiar?

Fossils show us what happens when Earth’s systems are pushed too far. They remind us that climate is not a constant, that life is resilient but not invincible. They give context to our current crisis, showing that we are not the first species to face global upheaval—but we might be the first to cause one.

In fossils, we find not only the echoes of past life, but warnings for our own.

Fossil Fuels and the Path Ahead

Despite their dangers, fossil fuels are still the dominant source of global energy. Transitioning away from them is one of the great challenges of our time. Renewable energy—solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal—offers hope. So do advancements in battery storage, hydrogen fuel cells, and nuclear fusion. But change is slow, and the political and economic structures that benefit from fossil fuels are deeply entrenched.

It is not enough to replace fossil fuels with cleaner alternatives. We must also redefine our relationship with the planet. Fossil fuels allowed us to live faster, larger, and more carelessly. But the Earth cannot sustain that pace. The reckoning is not only environmental—it is moral.

Do we burn the past for convenience, or learn from it for survival?

Two Paths, One Origin

Fossils and fossil fuels began as life. That is their common thread, their shared origin story in Earth’s deep time. But from that singular beginning, they split into two narratives—one that illuminates, and one that burns.

Fossils are the memory of life. They are quiet, patient, and generous. They wait to be discovered, to be read like ancient scrolls written in stone. They do not demand; they offer. They tell us where we came from, how we evolved, what we lost, and what we might become.

Fossil fuels are the fire of life. They are powerful, immediate, and insistent. They promise comfort, speed, and progress. But they also come with a price we are only now beginning to count: acidified oceans, smog-choked skies, flooded coastlines, and a climate on edge.

One is a window into Earth’s past. The other, a force that reshapes its future.

The Choice is Ours

We are the first species to unearth its own origins. We are also the first to decide what to do with that knowledge. The fossils beneath our feet tell us that life is both tenacious and fragile. They reveal a world in flux, where nothing—no species, no ecosystem, no climate—is guaranteed permanence.

And yet we burn that same past to fuel a future that may not be sustainable. We mine the memory of life to power conveniences that erode the very conditions that allow life to flourish.

This is not just a scientific distinction—it is a moral dilemma. It is a question of legacy. What do we want to leave behind? Will future generations find only the charred remains of our consumption, or will they find fossils of their own, untouched by crisis, preserved by wisdom?

Listening to the Earth

The Earth does not shout. It speaks in strata. It writes in fossils and whispers in isotopes. It shows us how species adapted, endured, or vanished. It reveals the deep interconnectedness of life and the narrow margins within which it can thrive.

Fossils are not merely curiosities of the past; they are guides. They remind us that our place in the universe is neither fixed nor guaranteed. They teach humility.

Fossil fuels, for all their utility, demand caution. They have shown us what we can achieve—but also what we can destroy. They are not inherently evil, but they are finite, and their unchecked use threatens everything we value.

To know the difference between fossils and fossil fuels is to understand the crossroads we stand upon. One represents knowledge; the other, power. One is a mirror; the other, a match.

We must decide what to carry forward—and what to leave buried.