Beneath our feet, beneath the cities and forests and oceans, lies a time capsule far older than human memory. It sleeps in layers of stone, pressed between epochs like a forgotten letter sealed by pressure and time. When we dig into the earth and find bones turned to rock, leaves preserved in shale, or even the ghostly imprint of a footstep hardened in ancient mud, we are not merely uncovering old debris. We are touching deep time. These are fossils—remnants of lives that once breathed, grew, hunted, flowered, and died in a world profoundly unlike ours.

But fossils are not just bones turned brittle. They are records, testimonies of evolution’s long and meandering path. They tell us not only about creatures long extinct but also about climates, ecosystems, and even cataclysms. Understanding fossils is like learning the language of the Earth’s memory, one syllable at a time.

The Birth of a Fossil: From Life to Stone

The story of how a fossil forms is, in its way, a tale of survival—not of the creature itself, but of its shape, its whisper, its last echo through time. The transition from living organism to fossilized relic is not common. In fact, it is rare, a statistical fluke made possible only by the right conditions at the right time in the right place.

Most living things do not become fossils. They rot, decay, are eaten or washed away. Only under specific circumstances can the process of decay be interrupted and redirected toward preservation. For fossilization to begin, death must often be sudden. A fish that sinks into an anoxic lakebed where bacteria struggle to survive; a fern buried by a sudden volcanic ashfall; a dinosaur overwhelmed by a flood and entombed in silt—these are some of nature’s unlikely candidates for fossil memory.

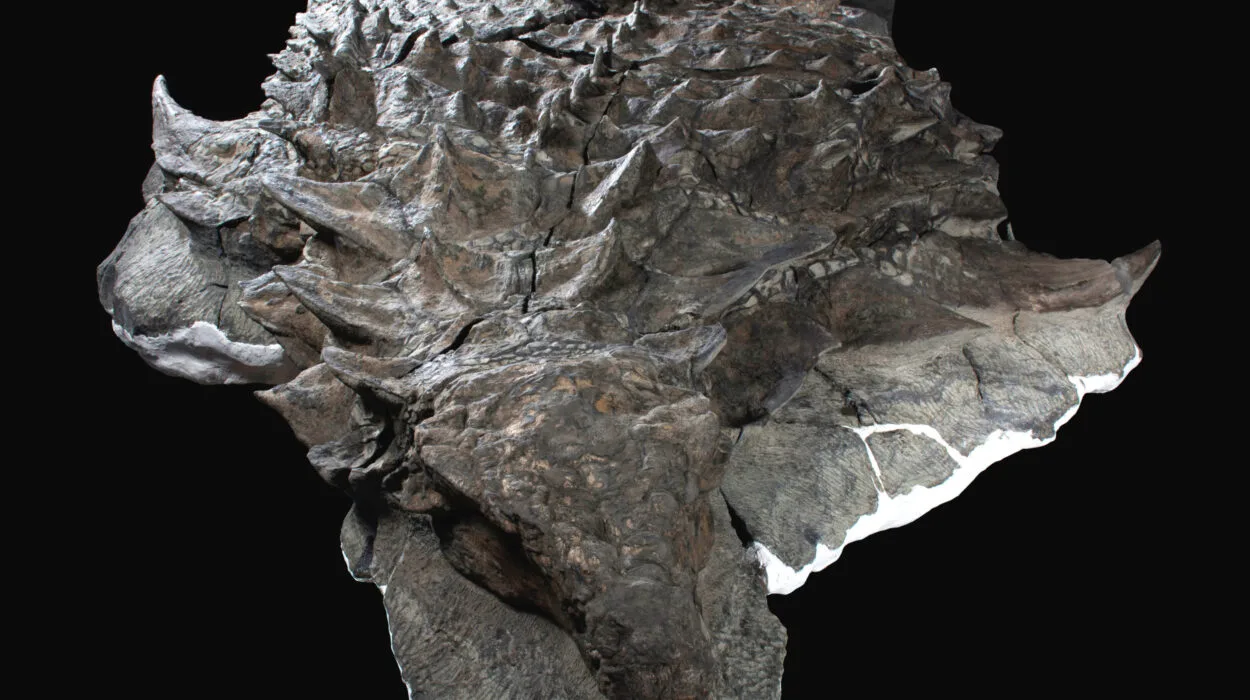

Once buried, the organic matter must be protected from scavengers and decay. Over time, layers of sediment continue to accumulate. As these layers thicken, pressure increases, and minerals in groundwater begin to infiltrate the buried remains. In some cases, the original organic material dissolves away completely, replaced molecule by molecule with minerals like silica, calcite, or iron, effectively turning bone into stone—a process called permineralization. In other scenarios, the organic body might leave an impression or cast, its form preserved in negative.

Fossilization, then, is not a single act but a process—a negotiation between decay and preservation, biology and geology. It is the Earth’s way of archiving lives it can never bring back.

Traces of Life: Not Just Bones

When we think of fossils, it’s tempting to imagine only the big, the dramatic—the tyrannosaur skulls, the mammoth tusks, the petrified tree trunks as wide as cars. But some of the most revealing fossils are the smallest, and some are not of bodies at all.

Trace fossils—also called ichnofossils—preserve the signs of life rather than the body itself. A trilobite’s shallow trail through Cambrian mud; a dinosaur’s three-toed footprint fossilized on a desert plain; even ancient coprolites, or fossilized dung, can tell us what extinct animals ate, how they moved, and how they lived.

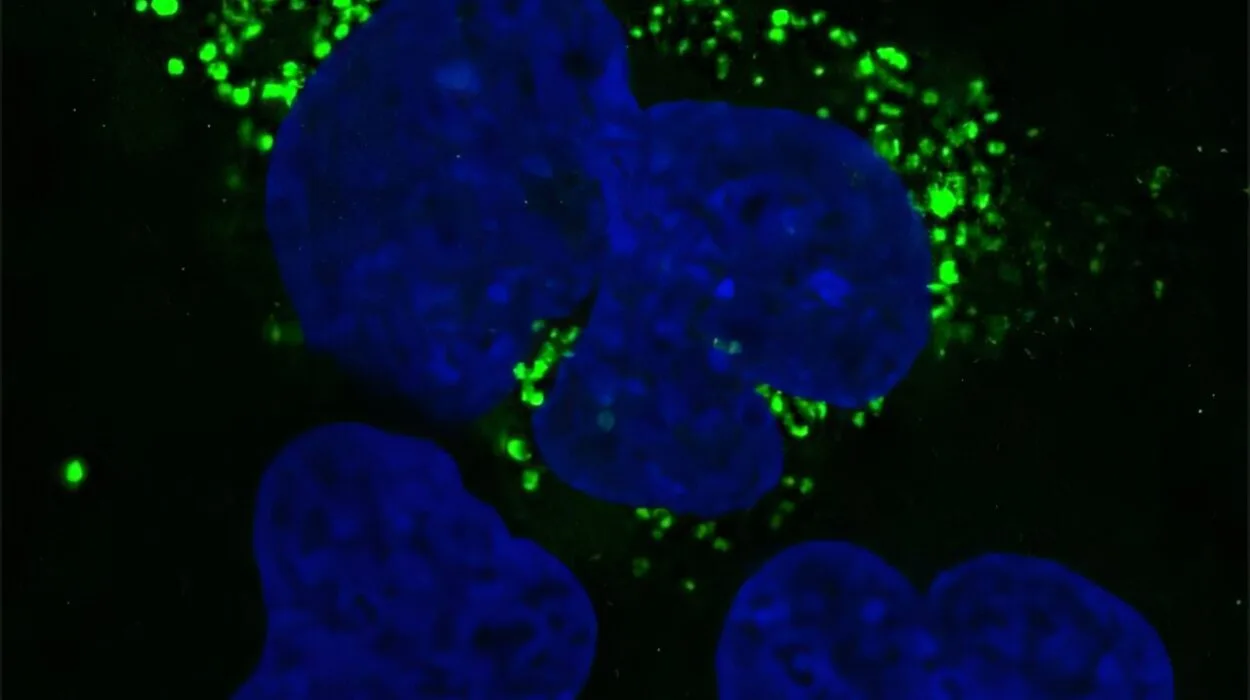

There are also microfossils—tiny remains of foraminifera, diatoms, and pollen grains—that are barely visible to the naked eye. These minute clues help scientists reconstruct climates and ecosystems with astonishing detail. Pollen trapped in layers of sediment can show how plant populations shifted over millennia, suggesting changes in rainfall or temperature. Diatoms embedded in lakebeds provide windows into ancient aquatic life.

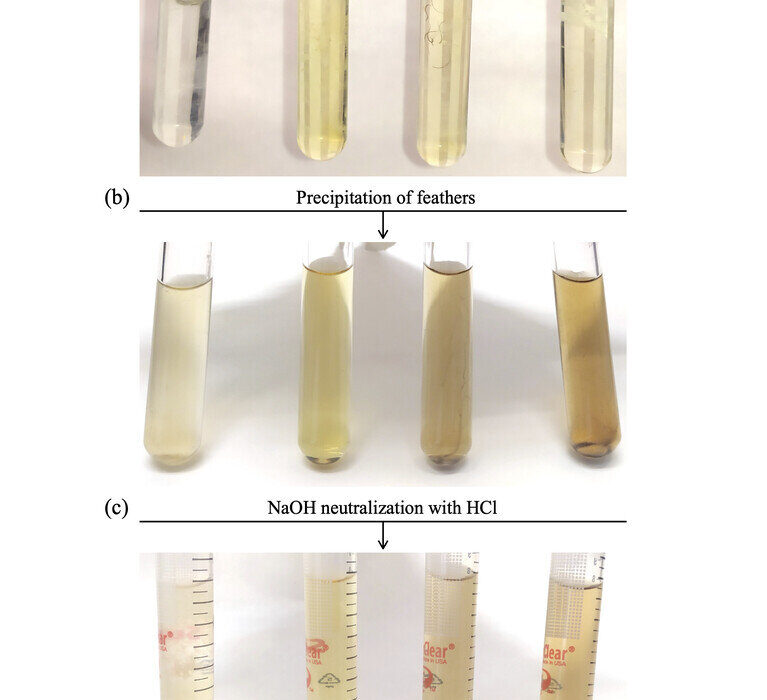

Even fossils of soft tissues, once thought impossible, are now occasionally found under rare circumstances. In certain fossil beds—known as Lagerstätten—exquisite conditions have preserved not just bones but feathers, skin, even organs. These precious finds transform skeletons into full characters, fleshed out with color, texture, and sometimes behavior.

Geological Time and the Language of Layers

To understand fossils is to understand time—deep time. Human history spans mere thousands of years, a blink compared to Earth’s 4.6-billion-year legacy. Fossils are embedded in rocks formed across vast geologic epochs, and their placement within sedimentary layers tells a chronological story.

Geologists divide time into eons, eras, periods, epochs, and ages. Each layer of sediment is like a page in a book, written slowly by rivers, seas, winds, and volcanic ash. The deeper the layer, the older the fossil it contains—this is the Law of Superposition, a foundational principle in geology.

But these layers are not always clean or orderly. Earth’s crust is restless. It folds, fractures, uplifts, and erodes. Fossils once buried beneath oceans may now rest atop mountains. Fossils displaced from their original contexts can complicate our readings, but they also challenge us to think like detectives, piecing together the full story from scattered, ancient clues.

Radiometric dating techniques—measuring the decay of radioactive elements—help place fossils within more precise timeframes. For example, the ratio of uranium to lead in a zircon crystal might reveal the age of the rock surrounding a fossil. This allows scientists not only to place fossils in time but also to reconstruct the grand sequence of life’s evolution.

Evolution Written in Stone

Charles Darwin once admitted that the fossil record, in his time, was frustratingly incomplete. He called it “imperfect” and compared it to a book with most of its pages torn out. Yet as the years have passed, the gaps have slowly filled in. Fossils are now among the strongest supports for evolutionary theory.

From the earliest microbial mats in stromatolites, some dating back over 3.5 billion years, to the sudden explosion of diversity in the Cambrian Period, to the slow march of fish onto land, then into reptiles, birds, and mammals—the fossil record maps life’s branching tree.

Transitional fossils—the ones linking seemingly distinct groups—are especially powerful. The discovery of Archaeopteryx in the 19th century, with both reptilian features and feathers, was an early indication of birds evolving from dinosaurs. More recently, fossils like Tiktaalik, a “fishapod” from 375 million years ago, have illuminated the water-to-land transition.

Yet evolution is not a smooth curve but a jagged, dynamic journey. Mass extinctions—like the Permian event that wiped out 90% of marine species or the asteroid-triggered end-Cretaceous extinction that doomed the dinosaurs—mark catastrophic interruptions in the fossil record. After each collapse, life rebounded, diversified, and adapted. Fossils capture both devastation and renewal.

Fossil Hunting: Art, Science, and Serendipity

To find a fossil is not just to locate a rock with a bone in it—it is to uncover a hidden life, a piece of the Earth’s long-forgotten story. Paleontologists, both professional and amateur, roam deserts, badlands, cliffs, and riverbanks searching for those hints of prehistoric time. The process is painstaking and often fueled as much by hope as by data.

In places like the Badlands of South Dakota, the Gobi Desert of Mongolia, or the fossil-rich limestones of Morocco, entire teams spend seasons excavating inch by inch, brush by brush. Every specimen must be documented in situ—its position, orientation, surrounding rock—all to preserve context.

Sometimes, discoveries are purely accidental. A rancher might spot a bone sticking out of a hillside. A child might stumble across a trilobite on a beach. In fact, some of the most significant fossil finds in history—like the first Neanderthal skull or Mary Anning’s legendary marine reptiles—were made by people outside the academic establishment.

What follows a discovery is a journey through preparation. Fossils are encased in plaster jackets for transport, then cleaned, analyzed, and often subjected to CT scans, chemical analyses, and 3D modeling. The moment of revelation—when a creature unseen for 100 million years emerges from rock—is one of quiet awe.

Fossils and Human Origins

Perhaps the most emotionally resonant fossils are those of our own ancestors. The study of human evolution—paleoanthropology—has been profoundly shaped by fossil discoveries across Africa, Asia, and Europe.

From the early australopithecines like “Lucy,” to Homo habilis with its stone tools, to Homo erectus with its long migrations and use of fire, fossils chart our evolutionary rise. The shape of a jawbone, the angle of a hip, the capacity of a skull—each detail informs how we became the thinking, tool-making, storytelling species we are.

Even the Neanderthals, once considered brutish cave-dwellers, have been reimagined through fossils and DNA as a sophisticated, symbolic people—close cousins rather than distant relics. Their bones tell of injury and care, burial, and possibly even ritual. Fossils, in this context, do more than teach us about survival—they suggest the roots of empathy, culture, and community.

The Ethics and Politics of Preservation

Fossils belong to no one and to everyone. They are part of Earth’s shared history, yet their discovery and custody raise ethical questions. Who has the right to excavate and keep fossils? Should private collectors be allowed to buy and sell them? What happens when fossils are removed from the countries where they were found?

Museums have long been the custodians of paleontological treasures, yet repatriation debates grow louder. Countries like Mongolia and Brazil are now asserting rights over fossils exported without consent. The issue becomes especially fraught when fossils of early humans—those that touch on our collective origin—are involved.

Another concern is conservation. Fossils, once exposed to air, are fragile. Climate change, erosion, and human interference threaten many fossil beds. Protecting these nonrenewable resources requires global cooperation and public awareness.

Fossil parks, digital archives, and open-access databases are emerging as ways to democratize fossil science. More and more, the goal is not just to own or display fossils but to share their stories with the widest possible audience.

Fossils and the Imagination

Beyond science, fossils captivate the imagination. They populate our myths and our media. From dragon bones in ancient China to the thunder beasts of Native American lore, humans have always been haunted by the evidence of ancient giants.

In modern times, films like Jurassic Park and exhibitions of towering dinosaur skeletons in natural history museums have turned fossils into cultural icons. Children clutch toy trilobites, and adults marvel at the sabertooth tiger’s skull. These symbols bridge the gap between fact and wonder, science and soul.

But the fascination is deeper than spectacle. Fossils remind us that we are not the first to walk this Earth and will not be the last. They confront us with the fragility of existence and the grandeur of time. They teach humility—and awe.

Looking to the Future with the Bones of the Past

Even as we look backward, new technologies are opening up fossil science in ways unimaginable a century ago. Synchrotron imaging allows researchers to see inside fossils without damaging them. Isotope analysis reveals what ancient creatures ate, how fast they grew, even how far they migrated.

Machine learning algorithms now scan fossil databases, finding patterns invisible to the human eye. Geneticists extract ancient DNA from bones, bridging paleontology with molecular biology. The result is a more vivid, detailed, and dynamic view of prehistoric life than ever before.

And yet, the core of paleontology remains a deeply human endeavor—curiosity, patience, reverence. To hold a fossil is to hold a fragment of a vanished world. It is to feel the Earth speaking across epochs.

Conclusion: Memory Etched in Stone

In the end, fossils are not just about the past. They are reflections of life’s resilience, creativity, and vulnerability. They show us that extinction and survival are two sides of the same coin, that every moment of life is part of a much larger narrative.

When we study fossils, we do more than analyze rock. We engage in an act of communion with the Earth’s history. We meet ancient strangers and recognize parts of ourselves. We see beauty not only in what has endured but in what has vanished.

Every fossil is a story. A fish that died in silence. A leaf that fell without fanfare. A dinosaur that left a footprint in wet clay. Each became a message in a bottle, sent forward through millions of years, waiting for someone to listen.

And when we do—when we truly hear what the stones are saying—we are not just learning about the past. We are being reminded of our place in the continuum of life, fragile yet enduring, a single breath in the Earth’s great and endless exhale.