In the dense rainforests of Africa, two of humanity’s closest living relatives—the chimpanzee and the bonobo—live lives far richer and more complex than they might first appear. A groundbreaking international study led by researchers from Utrecht University and Universidad Carlos III de Madrid has revealed that these great apes organize their social worlds in remarkably human-like ways.

By analyzing how chimpanzees and bonobos groom one another—a behavior that cements trust and friendship in ape societies—scientists have uncovered evidence that both species structure their relationships in layered “social circles” strikingly similar to those of humans. The findings, published in the journal iScience, suggest that the roots of our social behavior stretch far deeper into evolutionary history than previously thought.

Layers of Friendship in the Animal Kingdom

Humans naturally divide their social lives into tiers: intimate family and friends at the center, surrounded by circles of close friends, acquaintances, and distant contacts. This structure helps people balance the limits of time and emotional energy against the desire to maintain wide networks. Until now, it was unclear whether this pattern was unique to our species or shared with other intelligent primates.

To explore this, the research team—led by primatologist Edwin van Leeuwen—studied 24 groups of wild and captive chimpanzees and bonobos. Their focus was on social grooming, a behavior that goes beyond hygiene. For apes, grooming is a powerful form of social currency—a way to bond, resolve conflicts, and signal trust. By observing who groomed whom, how often, and for how long, the researchers could map out the invisible threads of friendship that hold ape societies together.

When they analyzed these patterns using mathematical models, the results were striking. Just like humans, both chimpanzees and bonobos appeared to invest most of their grooming effort in a small number of close companions, while still maintaining weaker bonds with many others. In other words, both species show a layered structure of relationships—small inner circles of intense social ties, surrounded by broader circles of looser connections.

The Chimpanzee’s Selective Nature

Though both species display human-like social organization, the study also uncovered fascinating differences between them. Chimpanzees, known for their complex political alliances and dominance hierarchies, turned out to be more selective in how they distributed their grooming time. They concentrated their attention on a few key partners—usually allies or trusted companions—and became even more selective as they aged.

This pattern mirrors a well-documented phenomenon in humans: as people grow older, their social networks shrink. They focus more on meaningful relationships and spend less time maintaining casual connections. According to Van Leeuwen, this parallel hints at a shared evolutionary logic behind social selectivity. “As individuals age, both humans and chimpanzees seem to prioritize depth over breadth in their relationships,” he explained.

For chimpanzees, whose lives often revolve around competition and cooperation within a strict hierarchy, maintaining a few strong alliances can be vital for survival. These close bonds help them navigate conflicts, defend territory, and secure access to resources. In such societies, friendship can literally mean the difference between life and death.

The Bonobo’s Egalitarian Heart

Bonobos, in contrast, tell a very different story. Sometimes called the “peaceful apes,” they are renowned for their gentle, cooperative nature and their tendency to resolve tension through play and affection rather than aggression. In the study, bonobos were found to distribute their grooming time far more evenly across group members, reflecting a more egalitarian social system.

Where chimpanzees often form exclusive alliances, bonobos seem to maintain fluid, open relationships. They live in communities where females tend to lead and where conflict is minimized through social harmony. Even strangers can be welcomed into a bonobo group with little hostility—a behavior rarely seen among chimpanzees.

Van Leeuwen suggests that this difference may explain why bonobos do not show the same age-related narrowing of their social circles as chimpanzees do. “Bonobos appear to live together in more fluid relationships, with social bonds that transcend group boundaries,” he said. “Their social world is more inclusive, which could be why they remain socially open throughout life.”

Shared Roots, Different Paths

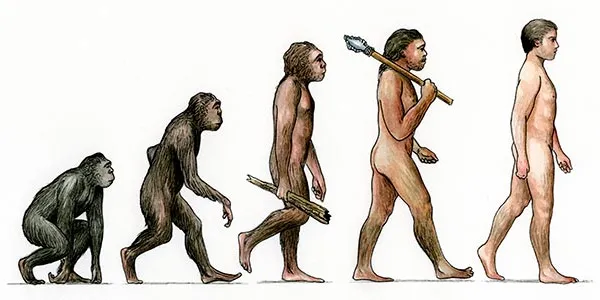

The parallels between human and ape social structures point to a deep evolutionary connection. The study suggests that the rules governing how individuals allocate time, attention, and emotional energy are not uniquely human—they are ancient strategies for managing social life that may have existed in our common ancestor millions of years ago.

“Our findings suggest that the fundamental rules guiding social effort allocation apply across multiple species,” said Van Leeuwen. “This reveals deep evolutionary continuity in how complex societies are organized.”

At the same time, the differences between chimpanzees and bonobos show that there is no single “correct” way to manage social relationships. Evolution has produced multiple successful strategies for living together—some based on tight, selective alliances, others on broader, more egalitarian networks. These strategies reflect the different ecological pressures and social needs faced by each species.

Chimpanzees, who often compete for food and territory, may have evolved to rely on strong, strategic partnerships. Bonobos, living in more resource-rich environments, could afford to adopt a more peaceful, cooperative approach. Both strategies, however, are remarkably sophisticated and reveal a high level of social intelligence.

The Mathematics of Social Connection

One of the most fascinating aspects of this study is the use of mathematical modeling to quantify social relationships. The researchers applied formulas similar to those used in human social network analysis to measure how apes distributed their limited grooming “budget.”

These models revealed patterns identical to those seen in human societies: an exponential decline in time and effort as relationships extend outward from the core circle. Just as humans can maintain only a limited number of close friendships due to time constraints—a phenomenon sometimes described by Dunbar’s number—chimpanzees and bonobos also appear to follow similar cognitive limits.

This mathematical similarity underscores the idea that social structure is not random. It emerges naturally from the constraints of brain size, energy, and time. The way both humans and great apes manage these constraints reveals the shared cognitive foundations of social life.

Lessons for Understanding Ourselves

Beyond its scientific significance, this research carries profound emotional and philosophical implications. It reminds us that the building blocks of friendship, trust, and cooperation are not uniquely human inventions. They are ancient, evolutionary tools that have shaped the lives of social species for millions of years.

Studying the social behavior of chimpanzees and bonobos offers a mirror for understanding our own lives. It helps explain why relationships matter so deeply to us—why we crave connection, invest time in loved ones, and organize our social worlds in predictable ways.

It also highlights how our emotional well-being depends on these social bonds. Just as isolation can cause stress and health problems in humans, apes deprived of companionship suffer anxiety and reduced survival. The need for connection, it seems, is written into our very biology.

Evolutionary Insights and Future Directions

The findings also open exciting new avenues for research. By comparing the social systems of closely related species, scientists can better understand how cooperation, empathy, and even morality may have evolved.

Van Leeuwen and his colleagues hope that future studies will expand this work to include other primates and perhaps even non-primate species. If similar social structures are found elsewhere in the animal kingdom, it would suggest that these patterns are not only ancient but universal.

“Understanding these patterns may reveal crucial insights for studying cooperation, social learning, and emotional well-being in both humans and other animals,” Van Leeuwen noted.

These insights could even inform modern human challenges—from building healthier communities to addressing loneliness in an increasingly digital age. By seeing ourselves as part of a continuum of social evolution, we gain perspective on what it truly means to be connected.

The Shared Thread of Friendship

Ultimately, the story of chimpanzees and bonobos is a story about us. It is about the bonds that sustain life, the friendships that shape our worlds, and the timeless dance of connection that links all social beings. Whether through a handshake, a shared meal, or a simple act of grooming, these gestures of care echo across species and through time.

From the forests of Africa to the cities of the modern world, the same invisible mathematics of affection governs how we love, cooperate, and coexist. In understanding our primate cousins, we do not just uncover the roots of our behavior—we rediscover the essence of what makes us human.

More information: Edwin J.C. van Leeuwen et al, The physics of sociality: Investigating patterns of social resource distribution among the Pan species, iScience (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.113507