Beneath our feet lies a story so vast and intricate that even the greatest novels pale in comparison. It is not written in ink or on parchment but in stone—layer upon layer of sediment, each fossil a letter, each rock formation a chapter. This story is Earth’s history, and the discipline that deciphers it is paleontology.

Paleontology is more than the study of ancient bones; it is a bridge between the living and the long-dead. It offers humanity a way to peer across the abyss of deep time, revealing a planet that has lived many lives, each different, each stranger than the last. Through fossils—preserved traces of ancient life—we piece together an epic that spans billions of years. These remnants of extinct organisms aren’t just scientific curiosities. They are messengers from lost worlds, offering us glimpses of tropical forests that flourished at the poles, oceans teeming with creatures beyond imagination, and catastrophic extinctions that reset life itself.

To understand paleontology is to stand at the crossroads of biology, geology, chemistry, and even astronomy. It’s where bones and rocks tell tales, where evolution walks hand in hand with erosion, and where curiosity becomes a compass guiding us into Earth’s most sacred archive.

The Origins of a Science Born from Curiosity

Long before paleontology became a formal discipline, people puzzled over the presence of seashells atop mountains and the fossilized remains of creatures that no longer existed. In ancient China, dragon bones were ground into medicine; in Europe, fossilized shark teeth were believed to be petrified tongues of serpents. It wasn’t until the Enlightenment that scholars began to see these remnants as clues to an ancient world.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, natural philosophers like Nicolas Steno and Georges Cuvier began laying the groundwork for modern paleontology. Steno proposed that sedimentary rocks formed in layers over time, trapping organisms that would later fossilize. Cuvier, through comparative anatomy, demonstrated that extinction was real, challenging the belief that all life had been created at once and remained unchanged.

With the advent of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection in the 19th century, paleontology found its place as the key to understanding life’s grand narrative. Fossils were no longer isolated curiosities—they became crucial evidence for how life changed over time, how species adapted, flourished, or vanished. Each new dig site became a potential revelation, each fossil a whisper from the past.

Decoding Earth’s Timeline

One of the most profound contributions of paleontology is its role in constructing the geologic timescale—a framework that organizes Earth’s 4.6-billion-year history into eons, eras, periods, and epochs. Without fossils, this timeline would be a blur. Through the patterns of fossil distribution, paleontologists identify major transitions in life’s history, such as the Cambrian explosion, when most major animal groups appeared, or the Permian-Triassic extinction, when over 90% of species perished.

Fossils act as time markers. Certain species only lived during specific periods, and their remains allow scientists to correlate rock layers across continents. This principle, called biostratigraphy, enables paleontologists to piece together a coherent narrative of Earth’s history even when direct dating methods fail.

Through this lens, paleontology transforms time into something tangible. We can imagine the Ordovician seas rich with trilobites, or the Cretaceous forests echoing with the calls of feathered dinosaurs. These are not mythologies—they are reconstructions based on careful, methodical work, grounded in stone and science.

Evolution’s Grand Canvas

Paleontology is the heartbeat of evolutionary biology. It shows us not just that evolution occurs, but how it unfolds across vast timescales. Through transitional fossils like Tiktaalik, which bridges the gap between fish and tetrapods, or Archaeopteryx, which links dinosaurs to birds, we see evolution not as a theory, but as a process as visible as erosion or volcanic eruption.

The fossil record is incomplete, as many organisms never fossilize and vast portions of Earth’s surface remain unexplored. Yet even in its incompleteness, it is rich with patterns. It reveals evolutionary radiation—bursts of diversification when new ecological opportunities arise. It shows convergence, where different lineages evolve similar traits, like wings or eyes. And it unveils extinction, the silent sculptor of biodiversity, which has reshaped life more than once.

Paleontology also deepens our understanding of adaptation. Consider the evolution of whales, whose ancestors walked on land. Their fossil lineage traces a remarkable journey from hoofed terrestrial mammals to the oceanic giants of today. This tale, preserved in stone, is more compelling than fiction because it is true.

Extinction and the Rebirth of Life

Perhaps no aspect of paleontology is as emotionally resonant—or as scientifically revealing—as the study of mass extinctions. There have been five major extinction events in Earth’s history, each reshaping the biosphere. The most famous, the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction, ended the reign of the dinosaurs around 66 million years ago. A space rock the size of a city struck Earth with such force that it ignited global wildfires, blocked sunlight for years, and collapsed ecosystems.

But extinction is not just an end. It is also a beginning. In the aftermath of such events, new life often emerges. Mammals, once small and nocturnal, rose to prominence after the dinosaurs vanished. Birds took to the skies, and flowering plants spread across continents. Paleontology shows us that life is both fragile and resilient. It warns us of the consequences of environmental disruption, yet it also inspires awe at life’s capacity to rebound.

By studying past extinctions, scientists gain crucial insights into present-day biodiversity crises. The patterns are eerily familiar: rapid climate change, habitat loss, and invasive species. Paleontology provides a long-term perspective that can inform conservation efforts and perhaps even guide us through our own era of ecological peril.

Earth’s Changing Climate and Shifting Continents

Paleontology doesn’t merely tell us about organisms—it also illuminates the environments they lived in. By analyzing fossil assemblages and the sediments they’re found in, paleontologists can reconstruct ancient climates, ecosystems, and even the positions of continents.

For instance, the presence of tropical plant fossils in the Arctic tells us that Earth has undergone dramatic climatic shifts. The discovery of marine fossils high in the Himalayas indicates that those rocks were once seafloor before tectonic forces thrust them skyward. Through these clues, paleontology helps chart the story of plate tectonics, the ever-drifting continents, and the supercontinents like Pangaea and Gondwana that came before.

By understanding ancient climate regimes—such as the greenhouse conditions of the Mesozoic or the ice ages of the Pleistocene—paleontologists help us place current climate change in context. The difference is speed. What once took millions of years is now unfolding in centuries. Fossils become more than relics—they become warnings etched in stone.

Microscopic Marvels and the Hidden Majority

When most people think of fossils, they picture towering dinosaurs or mammoth skeletons. But some of the most significant paleontological discoveries come from organisms too small to see without a microscope. Microfossils—like foraminifera, pollen grains, and diatoms—are the unsung heroes of Earth history.

These tiny organisms are incredibly abundant in the fossil record and evolve rapidly, making them excellent tools for dating rocks. They also record changes in ocean chemistry and climate. By examining their isotopic composition, paleontologists can infer ancient temperatures, ocean acidity, and even atmospheric CO₂ levels.

In deep-sea cores, these microfossils form a continuous archive of Earth’s climate over millions of years. Their patterns tell us when ice sheets grew and shrank, when ocean currents shifted, and when extinction loomed. They reveal a planet in constant flux and a biosphere dancing to rhythms older than humanity.

From Museums to Field Camps: The Human Side of Paleontology

Behind every fossil is a human story. Paleontology is a discipline rooted in exploration. It thrives on muddy boots, blistered hands, and the thrill of discovery. From the blistering badlands of Montana to the ancient shores of Morocco, paleontologists endure extremes to uncover the past.

Fieldwork is grueling and uncertain. A promising dig may yield nothing; an ordinary rock may hold a specimen that rewrites textbooks. But when a fossil emerges from the ground, cradled in plaster or wrapped in foil, it’s as if time itself has opened a door.

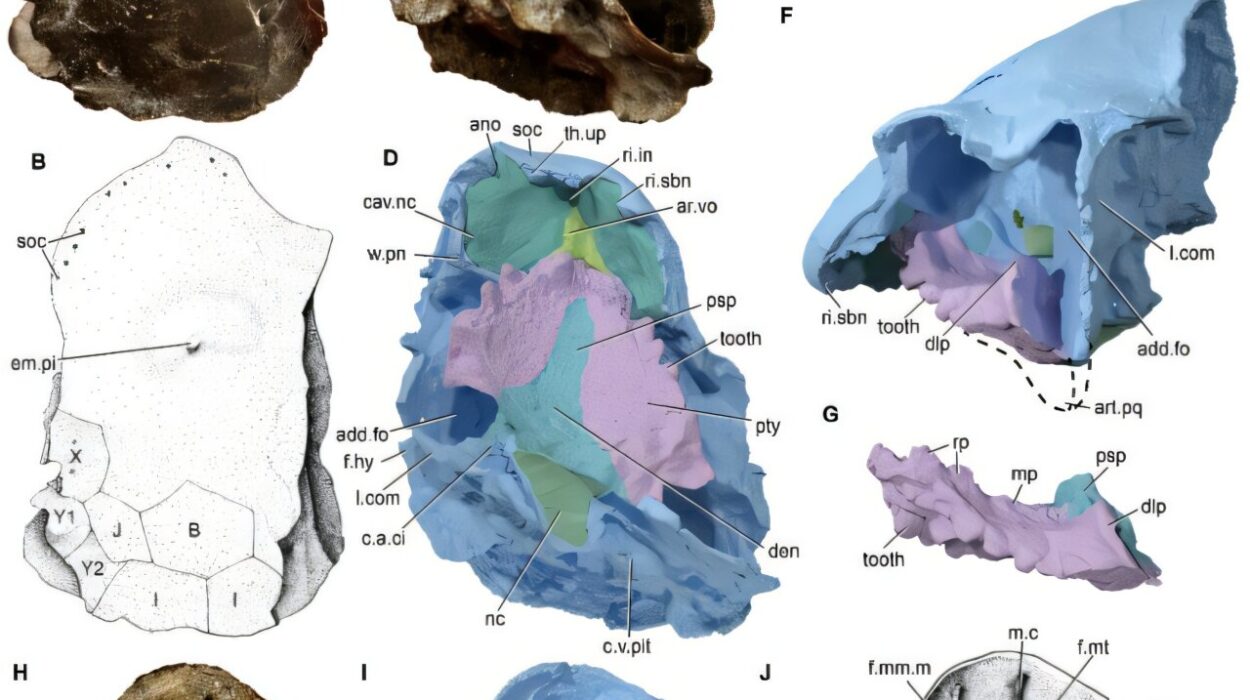

Museums, too, play a vital role. They are not merely places of wonder—they are centers of research. Each skeleton on display has likely passed through the hands of dozens of scientists. Behind the scenes, drawers brim with uncatalogued fossils, waiting for someone to recognize their significance. Modern techniques like CT scanning, 3D modeling, and isotopic analysis now allow us to explore fossils without destroying them, opening new frontiers in research.

Paleontology is also increasingly collaborative. It draws on genetics, computer modeling, climate science, and even artificial intelligence. It welcomes Indigenous knowledge and community involvement, challenging the colonial legacy of early fossil collecting. In this way, paleontology is evolving—just like the organisms it studies.

The Spirit of Wonder and the Weight of Time

To engage with paleontology is to step into a different scale of thinking. It invites humility. When you hold a trilobite that lived half a billion years ago, your own lifespan feels like the blink of an eye. When you trace the lineage of whales back to wolf-like ancestors, you begin to see yourself not as separate from nature but as part of its continuum.

Children often fall in love with dinosaurs, and for good reason—they are majestic, monstrous, and gone. But behind that fascination lies something deeper: a longing to understand the origins of life, the reasons for death, and the forces that shape our world.

Paleontology doesn’t provide easy answers. It teaches patience. It demands imagination tempered by evidence. It is both science and storytelling, rooted in data but soaring with wonder.

Toward the Future with Eyes on the Past

As we face an uncertain environmental future, paleontology offers a mirror and a map. It shows us what Earth has endured—and what it has lost. It reminds us that species come and go, that climates shift, and that nothing is forever. But it also offers hope. Life has rebounded from catastrophe before. New forms have emerged from the ashes of old.

In the age of climate change, habitat destruction, and extinction, paleontology’s relevance has never been greater. It teaches us to think in geologic time, to respect the fragility of ecosystems, and to cherish the only planet we know that harbors life.

It also reminds us that Earth is not static. It is alive, ancient, and ever-changing. In the fossils it preserves, we find not just evidence of what was—but also insight into what might be.

Echoes in Stone

In the end, paleontology is a conversation across time. It is a dialogue between the living and the long-dead, between the known and the unknowable. It is a science born of curiosity and sustained by awe.

When we gaze at the skull of a saber-toothed cat or the spiral shell of an ammonite, we do not just see extinct creatures—we see reflections of ourselves. We see the passage of time, the cycles of nature, the beauty of life in all its forms. We see warnings and wonders, beginnings and ends.

And we see, perhaps most profoundly, that we are not separate from Earth’s story. We are part of it—one more branch on the vast tree of life, whose roots stretch deep into the fossilized past.