For thousands of years, the sea off western France has moved back and forth over a hidden line of stone, unaware or unconcerned with what it was keeping secret. Only recently did that silence break. Divers, descending into the cold waters near the Ile de Sein in Brittany, came face to face with a wall that should not have been there. It stretched on for 120 meters, solid and deliberate, resting nine meters below the surface. Scientists say it has been underwater for around 7,000 years.

The wall was not alone. Nearby lay a dozen smaller structures, all shaped by human hands, all dating back to the same distant time. Together, they form a submerged landscape that once belonged to people who lived when the coastline looked very different from today.

The First Hint Appears on a Map

The story did not begin with divers, but with charts. In 2017, retired geologist Yves Fouquet was studying maps of the ocean floor produced using a laser system. These charts, designed to reveal the contours of the seabed, showed something unexpected near the Ile de Sein. Straight lines and shapes appeared where nature usually prefers curves and chaos.

Fouquet recognized that these patterns did not look natural. They suggested intention, planning, and construction. Yet at the time, they were only lines on a map, hints of something deeper. It would take years before anyone could be sure what they truly represented.

Entering a Harsh Underwater World

Between 2022 and 2024, divers finally explored the site directly. The waters off Brittany are not gentle. Currents are strong, visibility can be poor, and conditions change quickly. It is a place that challenges even experienced divers, let alone delicate archaeological work.

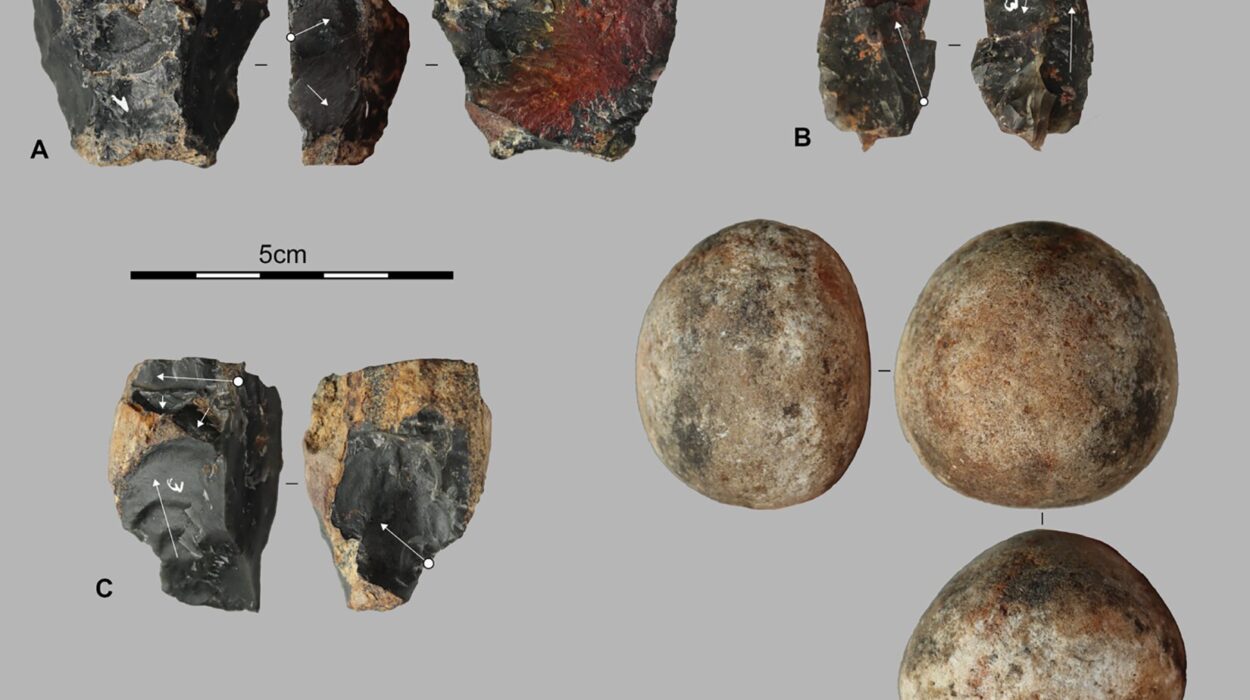

Despite these difficulties, the team confirmed what the maps had hinted at. The structures were real. They were made of granite. They had edges and forms that could not be explained by chance. They had survived centuries of waves, storms, and shifting sands.

“Archaeologists did not expect to find such well-preserved structures in such a harsh setting,” Fouquet said.

The preservation itself became part of the mystery. How had these stones endured so long in an environment that seems determined to erase human traces?

A Time When the Sea Was Far Away

Dating shows that the structures were built between 5,800 and 5,300 BC. At that time, sea levels were much lower than they are today. What is now an underwater site would once have been dry land, part of the foreshore where people could walk, work, and build.

The wall and its neighboring structures were not created beneath the waves. They were built in a landscape that has since been claimed by the sea. As water levels rose over millennia, the stones were gradually submerged, frozen in place as the shoreline retreated.

This slow drowning of the past turned ordinary constructions into time capsules, sealing them away until modern technology and patience brought them back into view.

What Were These Stones For?

Researchers are cautious in their interpretations, but they have proposed possibilities grounded in the structures themselves. The stones may have formed fish traps, built along the foreshore to take advantage of tides and marine life. Alternatively, they could have been walls designed to protect against rising seas, early attempts to manage an encroaching ocean.

Whatever their purpose, these were not casual piles of rock. The study emphasizes the effort behind them, stating that the structures reflect “technical skills and social organization sufficient to extract, move and erect blocks weighing several tonnes, similar in mass to many Breton megaliths”.

This description brings the builders into sharper focus. They were people capable of cooperation, planning, and heavy labor. They understood stone, weight, and stability. They organized themselves to shape their environment rather than simply adapt to it.

Before the Monuments We Thought Came First

One of the most striking implications of the discovery lies in its timing. The technical know-how required to build these submerged structures predates the first megalithic constructions by several centuries. Megaliths, large stone arrangements used as monuments or for ceremonial purposes, have long been seen as markers of advanced prehistoric societies in the region.

Yet here is evidence that similar skills existed earlier than previously thought. The ability to handle stones weighing several tonnes did not suddenly appear with monumental architecture. It was already present, practiced, and applied to practical needs long before stones were raised for ceremony or memory.

This challenges the timeline researchers have used to understand how and when complex building traditions developed.

Why This Discovery Matters Now

The wall beneath the sea off Brittany is more than an archaeological curiosity. It is a reminder that human history does not stop at today’s shoreline. Vast chapters of our past lie underwater, shaped by changing climates and rising seas.

This discovery matters because it reveals how adaptable and capable early societies were, even thousands of years ago. It shows that people responded to their environment with ingenuity, organization, and technical skill. It also demonstrates that significant traces of human life can survive in places we once assumed were too hostile to preserve them.

As scientists continue to explore submerged landscapes, finds like this reshape our understanding of where history can be found and how much of it remains hidden. The stones off the Ile de Sein tell a quiet but powerful story: long before the sea claimed this land, people were already leaving lasting marks upon it.