For centuries, archaeologists have pieced together humanity’s distant past through the fragments left behind—bones, tools, pottery, and ancient texts. Yet, sometimes the most surprising windows into history come from something as humble as a piece of discarded chewing gum. In recent years, scientists have begun uncovering the hidden stories sealed within ancient lumps of birch bark tar—sticky black resin that Neolithic people once chewed, molded, and used in their daily lives. What began as simple lumps of hardened sap has become one of the most extraordinary time capsules ever discovered.

The World’s Oldest Synthetic Substance

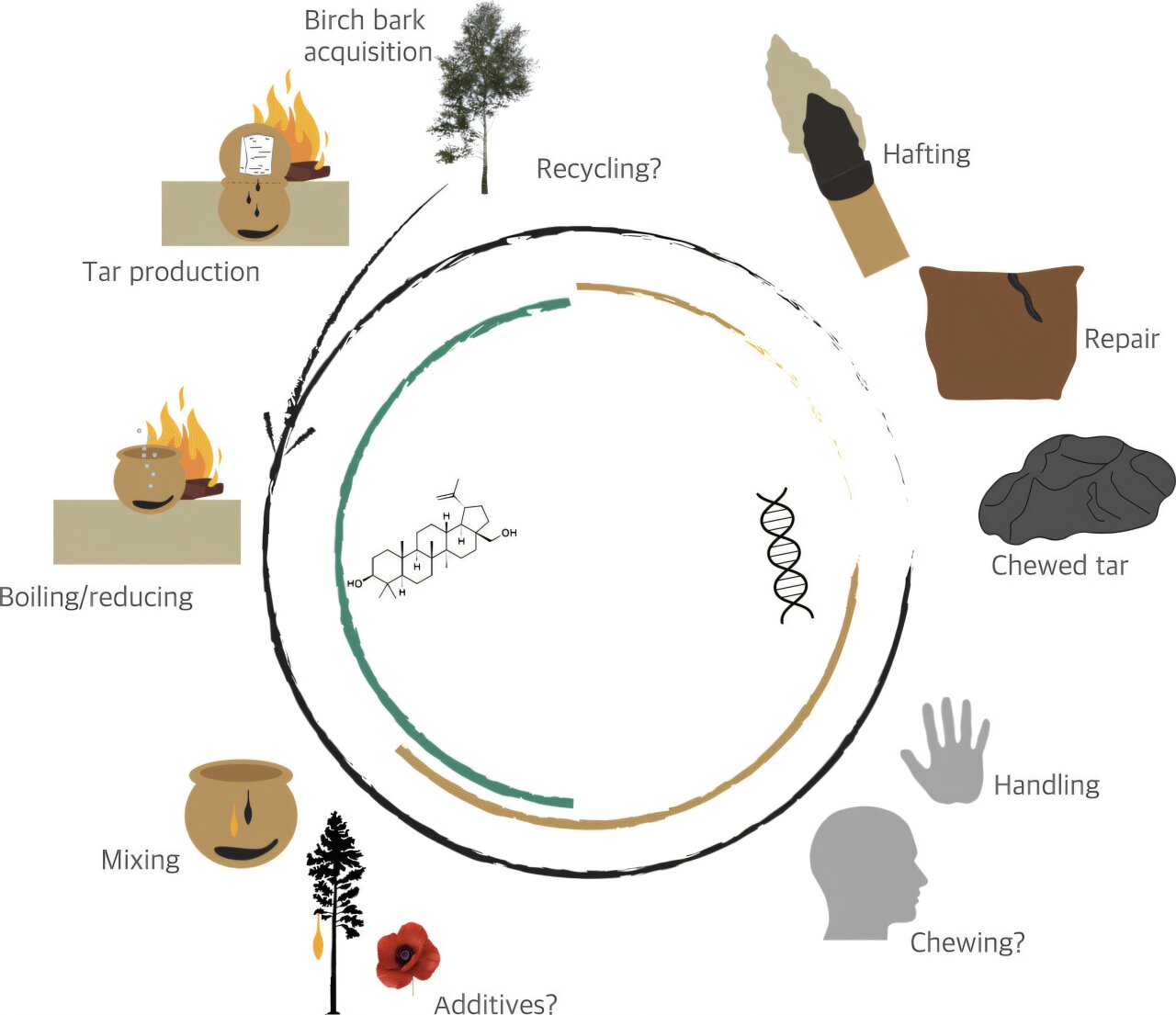

Birch bark tar is not a natural secretion—it is humanity’s first known synthetic material. Long before modern chemistry, Neolithic people discovered how to make it through fire and patience. By heating birch bark slowly in an oxygen-poor environment, they produced a black, glossy resin that could be molded, shaped, and used for a range of purposes. This resin had remarkable properties: it was waterproof, adhesive, flexible when warm, and durable when cooled.

Early humans learned to use birch tar to fix broken tools, attach stone blades to wooden handles, seal pottery, and even patch cracks in ceramics. It was, in essence, the prehistoric equivalent of modern superglue. But as researchers have now discovered, it was more than just a practical material—it was something deeply human.

A Sticky Clue to Daily Life

A new study led by archaeologist Hannes Schroeder and geneticist Anna White at the University of Copenhagen’s Globe Institute has illuminated the many roles of birch bark tar in Neolithic communities. Their research, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, analyzed 30 samples of tar collected from nine ancient settlements located mainly around lakes in the Alpine regions of Europe.

The team used two sophisticated methods to reveal the hidden history within these samples. First, chemical analysis confirmed that the black lumps were indeed birch bark tar. Then, ancient DNA analysis was used to search for traces of genetic material—an approach that, until recently, would have seemed impossible for such old and degraded materials. What they found was astonishing.

Several of the tar lumps contained human DNA, both male and female, as well as bacterial DNA that naturally occurs in the mouth. This meant that these pieces had been chewed—likely as a habit, a pastime, or perhaps even for medicinal reasons. Neolithic people might have softened the tar by chewing it before using it as glue, or they may have used it to soothe toothaches or clean their teeth. In that simple act of chewing, they left behind microscopic traces of themselves—tiny echoes of life from thousands of years ago.

The Taste of the Past

What makes this discovery even more intimate is the other DNA found trapped in the resin. Alongside the human genetic material, scientists identified traces of barley, wheat, beech, pea, and hazel—plants that were likely part of the chewers’ recent meals. These fragments offer a rare and tangible glimpse into what people were eating at the time.

The Neolithic period, spanning roughly from 10,000 to 4,500 years ago in Europe, marked a major transition in human history. Communities shifted from hunting and gathering to farming, domesticating plants and animals, and building permanent settlements. These tiny remnants of DNA provide direct evidence of the crops and foods that sustained these early farmers. The discovery of such traces in something as unassuming as a lump of tar reminds us how everyday habits—like chewing—can preserve the essence of ancient lives.

Tools, Repairs, and Ingenuity

The study revealed much more than just what Neolithic people chewed. Some of the birch tar was found not as discarded lumps but as residue on artifacts—a telltale sign of its use in craftsmanship. On flint blades, for instance, the tar was found precisely at the point where the blade would have been attached to a wooden handle, proving it was used as an adhesive in tool-making.

Other samples were recovered from pottery, often smeared along cracks or seams. The placement suggests the tar was used as a sealant or repair glue—a remarkably durable solution that likely kept pots watertight for years. In some cases, traces of plant DNA within the ceramic tar indicated the vessels may have been used for storing or cooking plant-based foods. Through these residues, archaeologists can reconstruct how Neolithic people solved practical problems, cared for their possessions, and managed their resources.

Preserving the Unpreservable

One of the most remarkable aspects of this research lies not in what the tar reveals, but in how it preserves. Organic remains like bones, skin, or teeth rarely survive in wet or acidic environments, such as those surrounding the Alpine lakes where these settlements once stood. Over millennia, the soft tissues of ancient people have long decayed—but the tar endured.

Birch bark tar is naturally water-resistant and antimicrobial, which means it can protect genetic material sealed inside. In essence, the chewed lumps acted as accidental preservers of DNA, trapping traces of saliva, food, and bacteria that would otherwise have vanished. This makes them priceless to scientists seeking to understand how ancient humans lived, worked, and even what they ate.

“This study underscores the value of integrating organic residue and ancient DNA analysis of archaeological artifacts to deepen our understanding of past cultural practices,” the researchers wrote. Indeed, the survival of such detailed biological information within this ancient resin opens up entirely new ways to study the lives of people who left no bones behind.

The Human Touch Across Millennia

There’s something profoundly emotional about these small, chewed lumps of tar. Unlike a spearhead or a pot, they were not crafted for display or long-term use. They were personal—used by someone’s teeth, held in someone’s mouth, perhaps chewed absently while sitting by a fire or working on a tool. Through DNA, we can now connect to those individuals directly.

Imagine a Neolithic woman by a lakeshore, reshaping her flint blade while chewing a piece of softened birch tar to make it pliable. Or a farmer’s child gnawing on it out of curiosity, unaware that thousands of years later, scientists would study their bite marks. These tiny, forgotten acts of everyday life remind us that the people of the distant past were not so different from us. They ate, they worked, they fixed broken things, and they sought small comforts—perhaps even a moment of idle chewing to pass the time.

Reconstructing a Vanished World

For archaeologists, discoveries like this are revolutionary because they fill in the spaces between grand events—the spaces where daily life happened. Bones and tools can tell us what people were, but not always who they were. The tar tells a different story, one of intimacy and routine. It reveals not just the technologies of survival, but the sensory and human aspects of life: texture, taste, and touch.

These discoveries also challenge old assumptions about what kinds of materials can preserve the past. By applying advanced DNA sequencing to substances once considered unimportant or mundane, researchers are finding new ways to reconstruct lost cultures. Ancient chewing gum, as it turns out, can carry more historical weight than entire libraries of written records—because it holds the actual biological traces of the people themselves.

A Legacy in Resin

The study of birch bark tar offers more than a glimpse into ancient craftsmanship or diet—it highlights the extraordinary resilience of human innovation. Thousands of years ago, people learned to transform natural materials to serve their needs. The creation of birch tar marked one of the earliest examples of chemical engineering, a process of invention that continues to define our species today.

In a broader sense, this discovery also reminds us of how intertwined our physical and cultural evolution has always been. The Neolithic period was a time of transformation, when humans began shaping not only tools and pottery, but entire ecosystems through farming. The ability to create substances like tar reflects the growing complexity of human thought—a step toward mastering nature through understanding and experimentation.

What Ancient Tar Teaches Us About Ourselves

Perhaps the most striking lesson from this research is how fragile yet enduring our traces can be. A few bites on a lump of birch tar, spat out and forgotten thousands of years ago, can now speak across ages, connecting us to those who came before. It shows that history isn’t only written in monuments or buried in tombs—it’s imprinted in the smallest, most personal gestures.

Through the lens of modern science, even something as simple as ancient chewing gum becomes a bridge between worlds. It tells us that the people of the past laughed, labored, and experimented; that they were ingenious, adaptable, and curious. In their resin-stained fingerprints, we find not just evidence of how they lived, but reflections of our own humanity.

More information: Anna E. White et al, Ancient DNA and biomarkers from artefacts: insights into technology and cultural practices in Neolithic Europe, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2025.0092