There are stories in human history that shimmer like mirages—half-truths, half-legends, balancing on the edge of memory. Among these is the tale of the Labyrinth of Egypt, a monumental structure described with awe by Herodotus, the Greek historian often called the “Father of History.” To him, it was no mere building. It was a wonder greater than words, a palace of passages and chambers so vast and intricate that he declared it surpassed even the Pyramids of Giza.

And yet, this labyrinth has been lost. No proud ruins greet the traveler at its supposed site. No soaring walls rise from the desert to testify to its grandeur. Instead, there is silence—sand, stone fragments, whispers carried by the Nile’s breeze, and the tantalizing accounts of ancient writers. The Labyrinth of Egypt lies in the realm between history and myth, waiting for truth to be rediscovered.

Herodotus Encounters the Labyrinth

In the 5th century BCE, Herodotus journeyed through Egypt, gathering stories and impressions of the land that was already ancient even then. He visited temples, observed the Nile’s floods, and studied the monuments of the Pharaohs. Among the marvels he described in his Histories was a colossal building near the town of Crocodilopolis (modern-day Faiyum).

Herodotus wrote that the Labyrinth contained twelve great courts, roofed and surrounded by halls, with three thousand rooms in total—half above ground and half below. The above-ground chambers, he claimed, he had personally seen and wandered through, marveling at their complexity. The underground chambers, however, were off-limits to him; the Egyptians explained they contained the tombs of kings and sacred crocodiles.

What struck Herodotus most was not simply the size of the labyrinth, but the sheer artistry of its construction. The walls were covered with carvings, the roofs of stone slabs, the chambers arranged in bewildering succession. For him, it surpassed all other monuments, even the famed pyramids.

Echoes from Other Voices

Herodotus was not alone in his description. Later writers also spoke of the labyrinth, adding layers to its legend. Strabo, the Greek geographer writing in the 1st century BCE, confirmed that such a structure had existed. He described it as a great roofed colonnade with numerous courts, built near Lake Moeris in the Faiyum oasis. Strabo marveled at its complexity, noting that it contained as many halls as there were nomes (districts) of Egypt, each with its own sacred shrine.

Pliny the Elder, in the 1st century CE, added yet another account. He suggested that the labyrinth had originally been constructed as a gathering place for the rulers of Egypt, a monument to political unity and religious devotion. To him, it was a testimony to Egyptian ingenuity, a structure of almost supernatural scale.

Even Diodorus Siculus, writing in the 1st century BCE, mentioned the labyrinth. He too spoke of its vastness and its association with sacred rites, particularly linked to Sobek, the crocodile god of the Nile waters.

Thus, the Labyrinth of Egypt was not a solitary invention of Herodotus’s pen, nor a lone traveler’s exaggeration. It was a story that persisted across centuries, retold by multiple observers, each lending credibility to the idea that something extraordinary once stood in the sands of the Faiyum.

The Pharaoh Behind the Mystery

If such a structure existed, who built it? Most accounts point to Amenemhat III, a Pharaoh of the 12th Dynasty during the Middle Kingdom, ruling in the 19th century BCE. Amenemhat III was a ruler of immense ambition, remembered for grand building projects, irrigation works, and his deep association with the Faiyum region.

The Labyrinth, according to many Egyptologists, was likely his mortuary temple at Hawara, a site south of modern Cairo. This temple, attached to his pyramid, was built not only as a place of worship but as a symbol of the Pharaoh’s might and his divine connection to the gods. Ancient writers may have encountered this temple in its full glory, interpreting it as a labyrinth because of its scale and intricacy.

The association with crocodiles is not coincidental. The Faiyum was a sacred region for Sobek, and temples dedicated to the crocodile god flourished there. If the labyrinth was indeed linked to Amenemhat III, its subterranean chambers might well have been intended as sanctuaries for Sobek’s cult animals or as royal tombs.

The Vanishing of the Labyrinth

If the Labyrinth was once so magnificent, why is it lost to us today? The answer lies in the passage of time, the cycles of decay, and the hand of human activity.

By the Roman period, many Egyptian monuments were being dismantled, their stones carted away to build new cities. Temples and tombs became quarries for later generations. The labyrinth’s great halls and roofs of stone slabs may have been plundered for building material, leaving only foundations buried beneath the shifting sands.

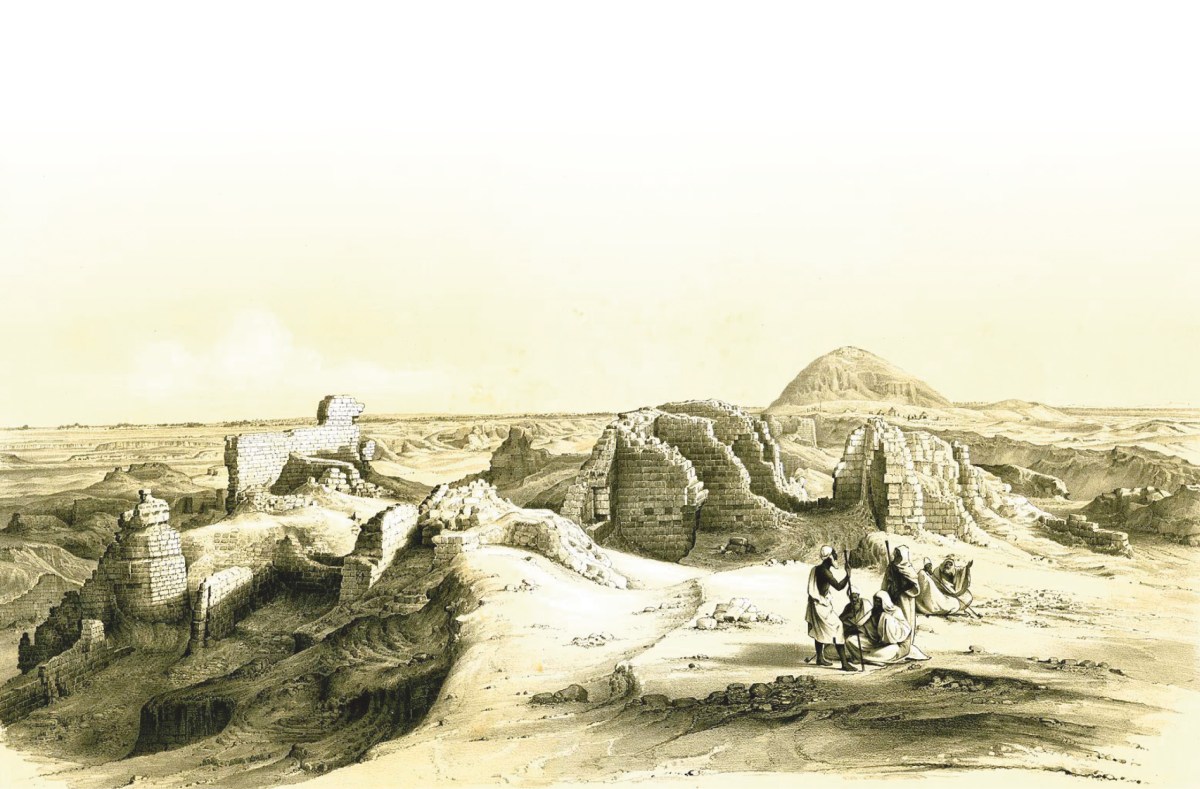

Earthquakes, floods, and the encroachment of the desert also played their part. What remains at Hawara today are little more than ruins—eroded blocks, fragments of columns, and traces of foundations. To the casual eye, they hardly speak of three thousand chambers or twelve vast courts. And yet, beneath the surface, archaeology suggests there is more than meets the eye.

Archaeological Glimpses

In the 19th century, European explorers and archaeologists sought the lost labyrinth with renewed vigor. In 1843, the German Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius identified the site of Hawara as the likely location of the labyrinth described by Herodotus. Later, the famed British archaeologist Flinders Petrie carried out excavations there in the 1880s.

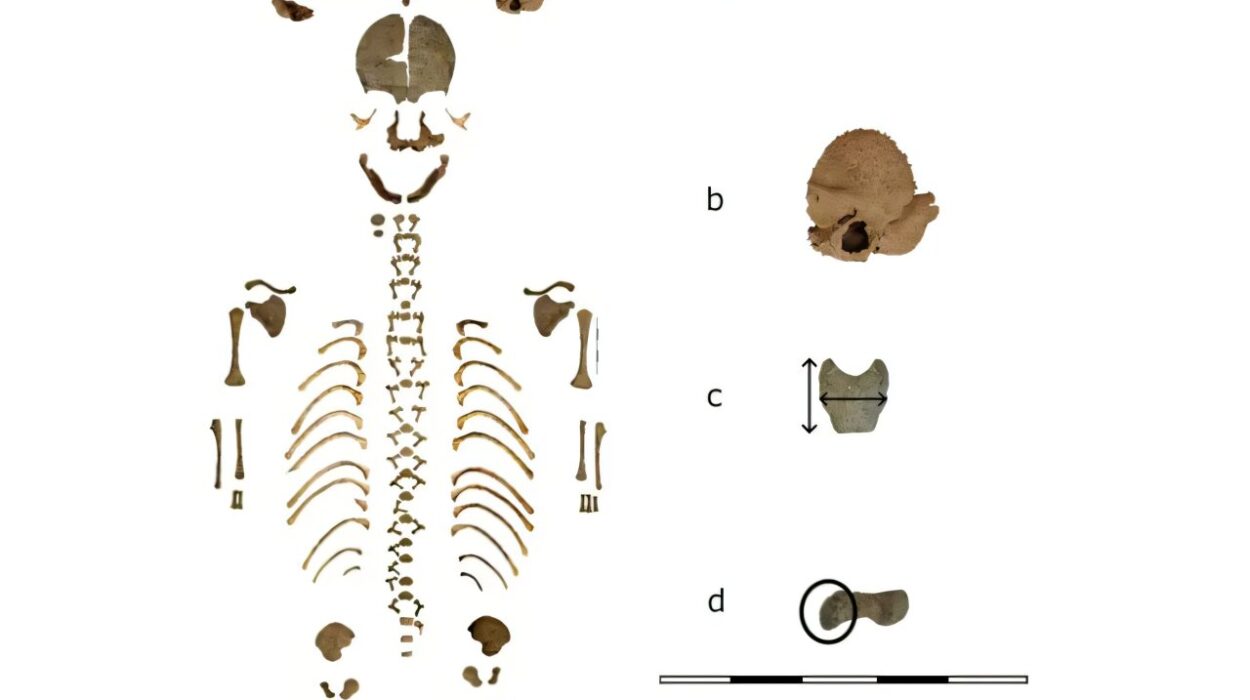

Petrie uncovered the remains of Amenemhat III’s mortuary temple, confirming its massive scale. He found evidence of an extensive complex with courtyards, colonnades, and chambers—though in a ruined state. The ground plan, reconstructed from the debris, revealed a bewildering series of rooms and passages, supporting the ancient descriptions of a labyrinthine layout.

More recently, modern surveys using ground-penetrating radar have hinted that beneath the surface may still lie vast structures waiting to be uncovered. Some researchers suggest that large portions of the labyrinth remain buried under layers of silt deposited by centuries of Nile floods. If so, the greatest parts of the labyrinth may still be hidden, awaiting excavation by future archaeologists.

Symbolism and Sacred Meaning

The labyrinth was not just an architectural marvel—it carried deep symbolic weight. To the Egyptians, the idea of a labyrinth could have represented the journey of the soul through the afterlife, a passage through complexity toward ultimate unity with the divine. The underground chambers associated with tombs and crocodiles reinforced this sacred dimension.

To later Greek and Roman writers, the Egyptian labyrinth also carried echoes of their own myths. The word “labyrinth” inevitably conjured thoughts of the Cretan labyrinth of King Minos, where the Minotaur lurked. Though the Egyptian labyrinth predates this Greek legend, the parallel may have added to its mystique in the classical imagination.

The labyrinth thus straddles the boundary between function and symbol—both a temple complex and a cosmic metaphor. It embodied Egypt’s grandeur, its religious devotion, and its mastery of stone.

A Wonder Greater Than the Pyramids?

Herodotus’s claim that the labyrinth surpassed the pyramids is striking. The pyramids remain visible today, immense and eternal, while the labyrinth has vanished. Yet his statement invites us to imagine what the labyrinth must have looked like in its prime.

Unlike the pyramids, which are monumental but relatively simple in design, the labyrinth was a sprawling complex of architecture, a living puzzle of halls, shrines, and chambers. Its grandeur lay not only in size but in intricacy—in the overwhelming sense of being surrounded by endless beauty, carvings, and sacred spaces. For a visitor like Herodotus, wandering its corridors must have been an awe-inspiring experience, a sensory overload that the static majesty of a pyramid could not replicate.

The Labyrinth and the Human Imagination

Even in its absence, the Egyptian labyrinth continues to live powerfully in human imagination. Its story raises questions about the fragility of memory and the endurance of myth. How can something once so magnificent disappear so completely? How much of what Herodotus wrote was literal truth, and how much was embellishment, filtered through the lens of wonder?

The labyrinth reminds us that human history is full of gaps, that our picture of the past is incomplete, like a shattered mosaic with missing pieces. It invites us to dream, to piece together fragments, to reconstruct what once was. It speaks to the yearning within us all: the desire to walk the forgotten corridors of time, to stand where ancient feet once stood, to touch a vanished world.

The Quest Continues

The mystery of the lost labyrinth is not closed. Archaeology is ever advancing, and the sands of Egypt have a way of yielding secrets when least expected. With modern technology, from satellite imaging to subsurface scanning, there is hope that more of the labyrinth may yet be uncovered.

If future excavations reveal the full extent of Amenemhat III’s temple, we may finally glimpse the structure that so awed Herodotus and Strabo. We may walk again through the courts and colonnades, tracing the paths of priests and pilgrims who once honored the crocodile god and the memory of a mighty Pharaoh.

Until then, the labyrinth remains both a mystery and a metaphor. It symbolizes the journey of history itself: complex, winding, full of dead ends and revelations, leading us deeper into the heart of human civilization.

Conclusion: The Enduring Allure of a Vanished Wonder

The Labyrinth of Egypt, as described by Herodotus, stands as one of history’s great enigmas. Whether as a literal temple complex at Hawara, a symbolic vision of the afterlife, or a half-forgotten monument lost to time, it continues to captivate us. It may no longer stand in visible stone, but it endures in words, in imagination, in the collective memory of humankind.

Perhaps that is the true power of the labyrinth—not just in its walls and chambers, but in the way it has compelled generation after generation to wonder, to search, to question. For in the lost labyrinth of Egypt, we see reflected our own eternal curiosity, our longing to uncover the hidden, and our recognition that history itself is a labyrinth we are forever trying to navigate.