At La Roche-à-Pierrot in Saint-Césaire, Charente-Maritime, archaeologists have uncovered something extraordinary: the oldest known workshop for making shell jewelry in Western Europe. Dating back at least 42,000 years, this discovery is more than a collection of shells and pigments—it is a direct link to the minds and imaginations of our ancient relatives. Found alongside the tools of Neanderthals and the remnants of their hunts, the site carries whispers of a world in transition, where Neanderthals and Homo sapiens may have lived side by side, exchanged ideas, and reshaped the course of human history.

The Châtelperronian Culture: A Bridge Between Worlds

The jewelry workshop belongs to what archaeologists call the Châtelperronian culture, a tradition that flourished in France and northern Spain between about 45,000 and 42,000 years ago. This culture sits at a pivotal moment in time, when Neanderthals, who had thrived in Europe for hundreds of thousands of years, encountered newly arrived Homo sapiens migrating from Africa. The Châtelperronian has long fascinated researchers because it represents one of the earliest industries of the Upper Paleolithic in Eurasia, yet its makers remain a mystery. Were these artifacts the final artistic achievements of Neanderthals, or do they reflect the influence—or even presence—of the first waves of Homo sapiens in Europe?

The jewelry workshop at Saint-Césaire brings us closer to answering this question, showing that these prehistoric artisans, whoever they were, were not only skilled hunters but also creators of symbolic objects that conveyed identity, status, and belonging.

Shells, Pigments, and the Birth of Symbolism

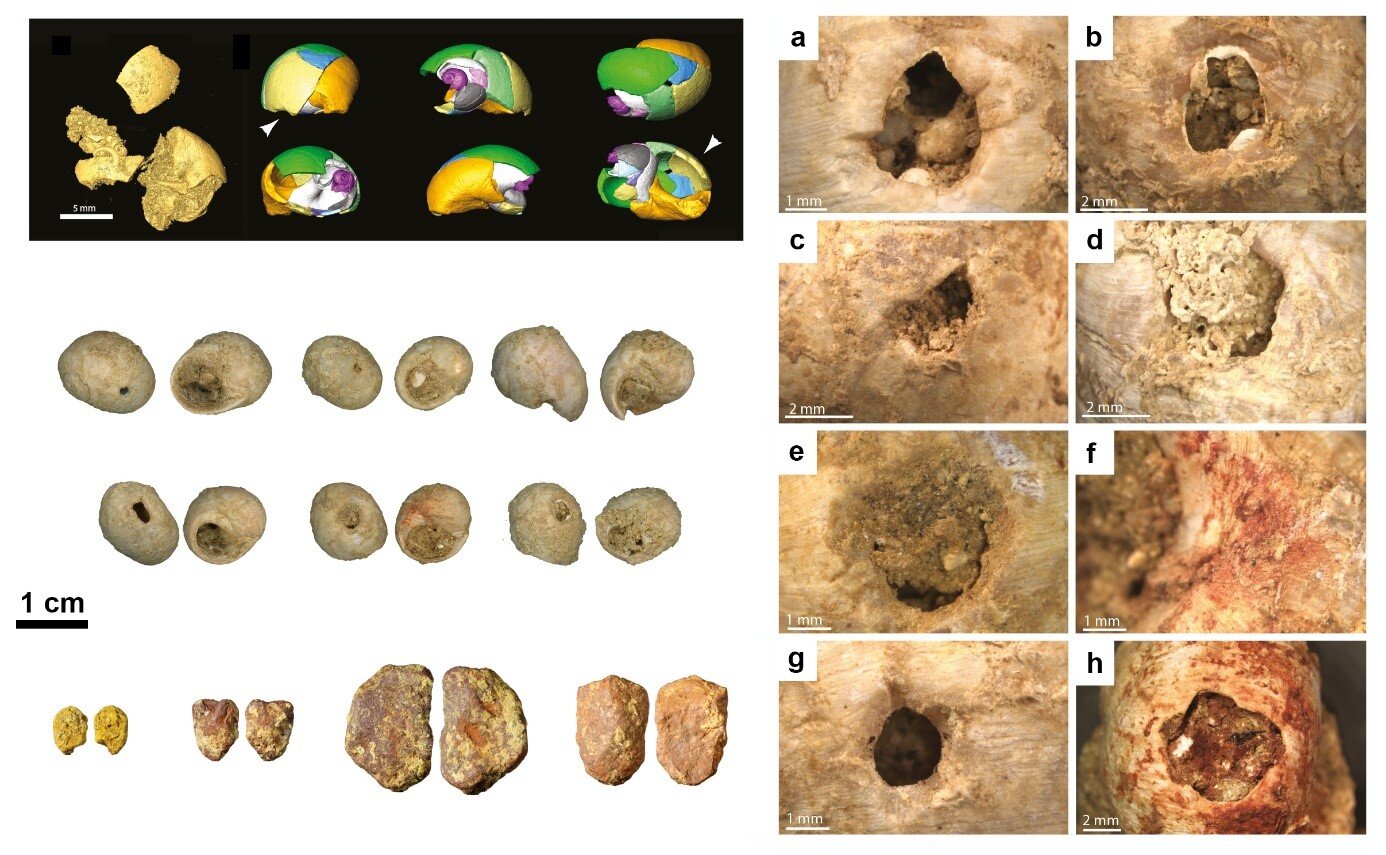

What makes the site remarkable is not simply the presence of beads but the clear evidence of production. Archaeologists found pierced shells, some unfinished, as well as shells left unperforated. This suggests a workspace dedicated to making ornaments rather than a random collection of decorative objects. Many of these shells had been brought from the Atlantic coast, more than 100 kilometers away from Saint-Césaire, while the red and yellow pigments used for coloring originated over 40 kilometers from the site.

This reveals two astonishing facts about these early people: first, that they valued beauty and expression enough to transport materials over long distances, and second, that they were part of a wider network of movement and exchange. The jewelry was not just decoration—it was part of a symbolic world, a way to mark identity, to signal group membership, or perhaps even to convey spiritual meaning.

Neanderthals, Homo Sapiens, and Shared Humanity

For decades, Neanderthals were often portrayed as primitive, lacking the symbolic thought that defined Homo sapiens. The discoveries at La Roche-à-Pierrot challenge this stereotype. Whether made by Neanderthals themselves or by groups of early Homo sapiens, the jewelry reflects a flourishing of symbolic behavior usually attributed only to our species. It suggests that Neanderthals were either capable of independent innovation or deeply influenced by contact with Homo sapiens.

The evidence of pigments, ornaments, and complex tools paints a picture of a community that thought in abstract terms, valued symbolic communication, and invested effort into beauty as much as survival. This is not the image of a species doomed to extinction but of one participating in the profound cultural transformations that shaped humanity’s shared past.

Life at Saint-Césaire: More Than Survival

Excavations also revealed tools typical of Neanderthals and the remains of hunted animals, such as bison and horses. These finds show that life at the site was multifaceted. People there were not only surviving by hunting and making tools; they were also experimenting with art, ritual, and symbolism. The jewelry-making workshop sits at the crossroads of necessity and imagination, reflecting both daily survival and the human need to create meaning.

Saint-Césaire was occupied for nearly 30,000 years by different groups, making it a unique archaeological treasure. Since the first excavations in 1976, and especially through new methods introduced since 2013, the site has continued to rewrite what we know about human evolution in Europe.

A Turning Point in Human History

The workshop at La Roche-à-Pierrot represents much more than the oldest shell jewelry in Western Europe. It is evidence of a cultural explosion at the dawn of the Upper Paleolithic, when ornamentation, social differentiation, and identity became central to human life. Jewelry here was not simply decoration; it was a statement, a symbol, a reflection of shared values and individuality.

By transporting shells and pigments over great distances, by shaping them into beads, and by wearing them on their bodies, these people were doing what humans still do today: using objects to tell stories about themselves and their communities.

Why This Matters Today

The discovery forces us to reconsider what it means to be human. Symbolism, creativity, and social communication were not exclusive to Homo sapiens. Neanderthals, too, were capable of shaping objects that carried meaning beyond function. Perhaps, instead of seeing Neanderthals and Homo sapiens as separate, competing species, we should imagine them as part of a continuum of human diversity—interacting, influencing, and shaping each other’s cultures.

In a world where we still search for identity and meaning through symbols, art, and shared traditions, the jewelry workshop at Saint-Césaire reminds us that this drive runs deep in our past. The beads and pigments created 42,000 years ago are not relics of a vanished world but echoes of a humanity we still recognize in ourselves.

A Legacy Carved in Shells

The shells from La Roche-à-Pierrot may be small, but their significance is immense. They capture a moment when imagination blossomed into material form, when survival intertwined with art, and when human groups—whether Neanderthal, Homo sapiens, or both—expressed themselves in ways that resonate across the ages.

The site remains a living laboratory for understanding how we became who we are. Each bead, each pigment-stained fragment, is a reminder that long before written language or grand civilizations, people found ways to tell stories, to connect, and to declare: we are here, and we are more than survival.

More information: François Bachellerie et al, Châtelperronian cultural diversity at its western limits: Shell beads and pigments from La Roche-à-Pierrot, Saint-Césaire, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2508014122