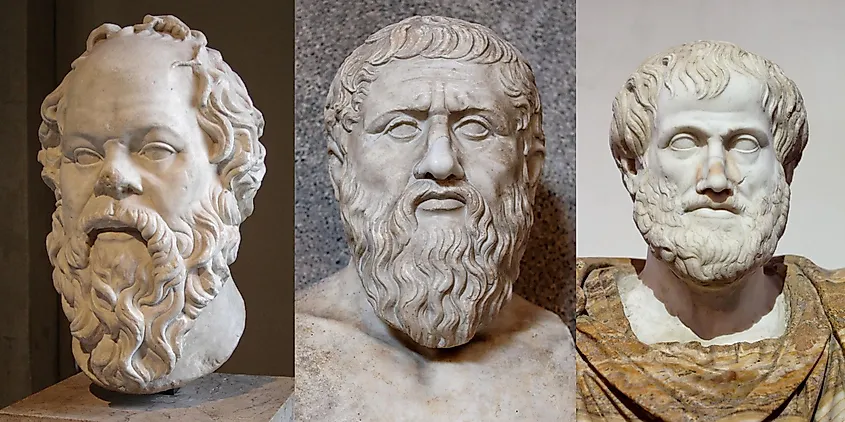

Western philosophy, as we know it today, was born in the bustling, sunlit streets of ancient Athens. The 5th and 4th centuries BCE were a time of intellectual ferment, political experimentation, and cultural flowering in Greece. It was during this remarkable age that three thinkers—Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle—shaped the foundation of philosophy. Their ideas have echoed across centuries, shaping law, science, ethics, art, and politics, influencing civilizations long after their own world had crumbled into ruins.

These men were more than abstract thinkers. They were teachers, rebels, and visionaries. They wrestled with questions that remain alive today: What is justice? What is truth? How should we live? What is the nature of reality? Their lives and ideas remind us that philosophy is not a sterile enterprise of definitions and arguments but a lived practice—a dialogue between thought and existence.

To explore Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle is to walk into the very heart of philosophy itself. Their intellectual lineage is like a chain of torches: Socrates lit the fire of inquiry, Plato carried it forward into a world of ideas, and Aristotle turned its flame into a disciplined system of knowledge. Together, they transformed not only Athens but also the destiny of human thought.

Socrates: The Gadfly of Athens

Socrates (469–399 BCE) is perhaps the most enigmatic of philosophers. He left no writings of his own, and what we know of him comes from his students—chiefly Plato and Xenophon—as well as from contemporary dramatists such as Aristophanes. Yet, despite this absence of written words, Socrates stands at the beginning of Western philosophy, not merely as a thinker but as a way of life.

Socrates lived simply, rejecting wealth, power, and conventional honors. He roamed the Athenian agora, engaging anyone willing to talk, from generals to shoemakers. With relentless questions, he challenged assumptions, exposed contradictions, and pushed people toward self-examination. He compared himself to a midwife, helping others give birth to ideas, or a gadfly, stinging the city of Athens out of complacency.

At the core of Socrates’ method was the belief that wisdom begins with recognizing one’s own ignorance. “The unexamined life is not worth living,” he declared. His dialogues often ended in aporia—a state of puzzlement—but this was not failure. For Socrates, acknowledging ignorance was the first step toward genuine knowledge and virtue.

Socrates cared deeply about ethics. He asked what it meant to live a good life, to act justly, to cultivate the soul. He believed that wrongdoing stemmed from ignorance: no one does evil knowingly. Thus, philosophy was not an abstract pursuit but the very heart of moral existence.

His relentless questioning, however, made him many enemies. In 399 BCE, he was tried on charges of impiety and corrupting the youth of Athens. Offered the chance to escape, he refused, choosing to uphold the laws of his city even when they condemned him unjustly. Drinking the cup of hemlock, he died a martyr to philosophy, leaving behind a legacy of courage and intellectual honesty that has never faded.

Plato: The Philosopher of the Ideal

Plato (427–347 BCE), Socrates’ most famous student, carried his teacher’s legacy into a grand philosophical system. Unlike Socrates, Plato wrote extensively, leaving behind dialogues that remain some of the most brilliant works in world literature. In them, Socrates often appears as the main character, continuing to question, challenge, and reveal truth. Yet through these dialogues, Plato’s own vision emerges—an ambitious exploration of reality, knowledge, politics, and the human soul.

Plato was deeply marked by Socrates’ death. He came to believe that the instability of Athenian politics, with its swings of opinion and mob judgments, revealed the need for a higher, more stable truth. This conviction led to one of his most enduring ideas: the theory of Forms.

According to Plato, the world we perceive with our senses is not the ultimate reality. It is a shifting, imperfect reflection of eternal, unchanging Forms—or Ideas. Beauty, justice, goodness, equality—these exist in their purest form beyond the material world, and our world is but a shadow of them. Just as a sculptor can only approximate the ideal of beauty, so the material world can only reflect the perfect Forms.

Knowledge, then, is not mere sensory experience but recollection of these higher truths. In his famous Allegory of the Cave, Plato describes humanity as prisoners chained in a cave, mistaking shadows on the wall for reality. The philosopher is the one who escapes, sees the light of the sun, and returns to guide others.

Plato also envisioned a radical political philosophy in his dialogue The Republic. He argued that society should be governed not by wealth or birth but by philosopher-kings—those who have ascended to the realm of Forms and grasped true justice and wisdom. While critics see this as utopian, Plato’s ideas continue to provoke debates about governance, education, and the role of philosophy in politics.

Plato founded the Academy in Athens, one of the earliest institutions of higher learning in the Western world. Here, philosophy was cultivated not as an occasional pastime but as a lifelong pursuit, nurturing generations of thinkers—including Aristotle.

Aristotle: The Master of Those Who Know

Aristotle (384–322 BCE), Plato’s student, would chart his own path, one both rooted in and divergent from his teacher’s. If Plato was the philosopher of transcendent ideals, Aristotle was the philosopher of empirical reality. He believed truth could be found not in a world beyond but in careful observation of this world.

Aristotle was a polymath whose writings spanned logic, biology, physics, ethics, politics, rhetoric, and aesthetics. His approach was systematic, seeking to classify, categorize, and understand the principles of everything from plants to constitutions. For this reason, later generations called him “the master of those who know.”

At the heart of Aristotle’s philosophy was the idea of teleology—that everything in nature has a purpose, an end (telos) toward which it strives. A seed strives to become a tree, a human strives for eudaimonia—flourishing or fulfillment. This view infused his ethics: the good life is one lived in accordance with reason, cultivating virtues such as courage, justice, and moderation. Virtue, for Aristotle, was not extreme but a mean between excess and deficiency.

In politics, Aristotle studied existing constitutions, seeking to understand what kinds of government best promote human flourishing. Unlike Plato’s idealized republic, Aristotle preferred practical analysis. He recognized that states must balance the interests of different groups, and that stability often requires compromise.

Aristotle’s contributions to science were equally profound. He dissected animals, studied plants, and tried to classify living things systematically. Though many of his conclusions were later revised, his method of observation and categorization laid the groundwork for biology and natural science.

He also developed formal logic, constructing the syllogism—an argument form that became the backbone of reasoning for centuries. Even today, logic and rhetoric remain indebted to Aristotle’s insights.

After Plato’s death, Aristotle tutored Alexander the Great, a relationship that symbolically united philosophy and empire. Later, he founded his own school, the Lyceum, where students walked as they learned, giving rise to the name “Peripatetics.” His works, encyclopedic in scope, became central texts for both Islamic and Christian scholars in the Middle Ages, shaping theology, science, and philosophy.

Philosophy as a Way of Life

Though their methods differed, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle shared a conviction: philosophy is not merely theory but a way of life. For Socrates, it was the relentless questioning of assumptions and dedication to virtue. For Plato, it was the ascent to higher truths and the shaping of a just society. For Aristotle, it was the cultivation of reason and virtue in harmony with the natural world.

Their lives also remind us that philosophy is inseparable from its historical context. Socrates lived during the turbulence of Athens’ democracy and war. Plato grappled with the city’s decline and envisioned a more stable order. Aristotle observed both the practical realities of politics and the vastness of nature, seeking to make sense of the world as it was.

Together, they created the foundation of Western philosophy, influencing later thinkers from Augustine to Aquinas, from Descartes to Kant, from Nietzsche to modern scientists and ethicists. Their questions remain ours: What is justice? What is truth? How should we live?

The Enduring Legacy

The legacy of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle is not confined to history books. It permeates our modern world. When we speak of ethics in medicine, of democracy in politics, of logic in argument, or of science in inquiry, we are heirs to their thought. Universities, academic disciplines, and even the very idea of critical inquiry owe much to their pioneering work.

Socrates’ courage in questioning authority inspires the freedom of thought and speech we value today. Plato’s vision of ideals challenges us to strive for justice and wisdom beyond the immediate and the imperfect. Aristotle’s embrace of observation and reason laid the foundations for science, making him as much a progenitor of biology and physics as of philosophy.

Their disagreements, too, remind us that philosophy thrives on dialogue, not dogma. The tension between Plato’s idealism and Aristotle’s empiricism continues to shape debates in philosophy, science, and politics. Socrates’ refusal to write reminds us that philosophy is alive in conversation, in questioning, in the living mind.

Conclusion: The Great Conversation

Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle were not merely philosophers of ancient Greece; they were initiators of the Great Conversation that still continues. Their words, questions, and arguments cross the centuries, inviting each generation to think anew. They remind us that philosophy is not about memorizing doctrines but about engaging with life’s deepest questions.

We are still in their company whenever we ask, “What is the good life?” or “What is truth?” or “How can society be just?” Their answers may differ, but their spirit of inquiry endures.

In the end, to study Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle is to encounter not only the past but also ourselves. For philosophy, as they taught us, is not something external—it is the mirror in which humanity seeks to see its own soul.

And as long as we continue to ask questions, as long as we dare to examine life, the legacy of these great philosophers will never fade.