For centuries, the story of humanity’s transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age has carried a sense of mystery. How did people first learn to smelt iron from rocks and turn it into tools, weapons, and the raw material of civilization? Now, research from Cranfield University is shedding light on this turning point in human history, offering a picture not of sudden invention but of gradual, curious experimentation by Bronze Age copper smelters.

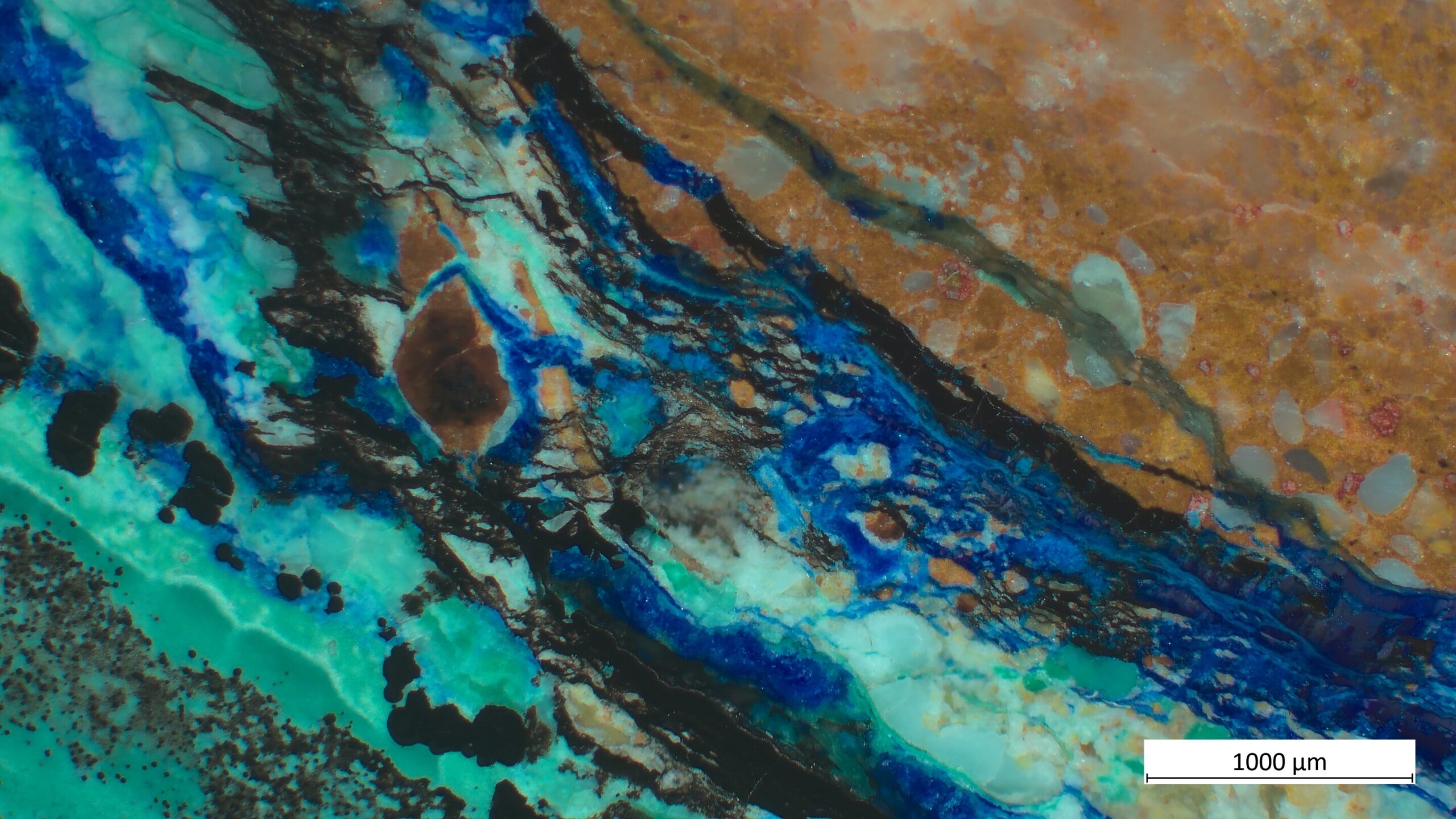

At the heart of this discovery is a 3,000-year-old metallurgical workshop at Kvemo Bolnisi in southern Georgia. First studied in the 1950s, the site contained curious piles of hematite, a mineral rich in iron oxide, as well as large deposits of slag—the waste left behind from metal production. Archaeologists at the time assumed they had found one of the earliest iron-smelting sites, a place where ancient workers were already producing iron in earnest.

But fresh analysis tells a different, more subtle, and perhaps more fascinating story.

Copper, Not Iron—But a Critical Step

According to the new study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, the ancient metallurgists at Kvemo Bolnisi were not smelting iron at all. Instead, they were producing copper, the defining metal of the Bronze Age. Yet here lies the breakthrough: they were using iron oxide as a flux, a material added into the furnace to make the smelting process more efficient and to yield purer copper.

This means that Bronze Age copper workers were deliberately handling and experimenting with iron-rich minerals inside their furnaces long before true iron smelting was discovered. In doing so, they were unknowingly laying the foundations of the Iron Age. Their workshops became laboratories of transformation, where trial and error with unfamiliar materials gradually unlocked one of humanity’s most transformative technologies.

Dr. Nathaniel Erb-Satullo, Visiting Fellow in Archaeological Science at Cranfield University, explains the significance: “Iron is the world’s quintessential industrial metal, but the lack of written records, iron’s tendency to rust, and a lack of research on iron production sites has made the search for its origins challenging. That’s what makes this site at Kvemo Bolnisi so exciting. It’s evidence of intentional use of iron in the copper smelting process.”

From Sky Iron to Earth Iron

Iron itself was not new to these ancient people. For millennia before the Iron Age, rare iron artifacts had been crafted from meteorites—chunks of metallic iron that fell from the sky. One of the most famous examples is the dagger buried with the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun, forged from extraterrestrial iron and adorned with a golden hilt. Such objects were treasures beyond value, rarer than gold, and imbued with spiritual or royal significance.

But these artifacts were exceptions. Naturally occurring metallic iron is vanishingly rare on Earth. What transformed human history was not the discovery of iron as a substance but the ability to extract it from iron ore—rocks rich in compounds like hematite. This required a leap in both imagination and technical skill, because smelting iron demands far higher temperatures and more complex furnace conditions than copper or bronze.

The reanalysis of Kvemo Bolnisi suggests that this leap was not sudden inspiration but the outcome of countless small experiments by copper smelters who already understood the furnace as a place of transformation. By adding iron oxides as fluxes, they were taking their first, perhaps accidental, steps toward a new age.

The World Transformed by Iron

When extractive iron metallurgy finally emerged, it reshaped civilization. Unlike copper and tin—the ingredients of bronze—iron was abundant. Entire mountainsides could be mined for iron-rich rocks. Once the technology to smelt it became widespread, iron tools, weapons, and infrastructure spread across societies, empowering empires like Assyria, Greece, and Rome, and later fueling the Industrial Revolution’s trains, factories, and steel-framed cities.

The Iron Age was not a sharp break but a gradual transformation, unfolding unevenly across regions. In some areas, bronze and iron coexisted for centuries. Yet the momentum was unstoppable: iron’s abundance, strength, and versatility eventually made it the defining metal of human progress.

Reading Ancient Minds Through Slag

What makes the Kvemo Bolnisi findings particularly moving is not just the technical insight but the human story it reveals. The slag and mineral piles, once dismissed as waste, now read like the notes of ancient experimenters—evidence of trial, error, and curiosity. “There’s a beautiful symmetry in this kind of research,” Dr. Erb-Satullo reflects. “We can use the techniques of modern geology and materials science to get into the minds of ancient materials scientists. And we can do all this through the analysis of slag—a mundane waste material that looks like lumps of funny-looking rock.”

In these lumps of slag, we glimpse the ingenuity of anonymous copper smelters, men and women working with fire and stone to push the limits of what was possible. They may not have realized it at the time, but their willingness to experiment with new materials laid the groundwork for one of the greatest technological revolutions in history.

A Continuum of Curiosity

The transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age was not the story of a single invention or a sudden spark of genius. Instead, it was the outcome of centuries of cumulative curiosity—of people who tested, tinkered, and dared to combine the familiar with the unfamiliar. The new research from Cranfield University helps us see that process more clearly, not as a clean divide between ages, but as a continuum of experimentation.

In that sense, the story of Kvemo Bolnisi is not just about the origins of iron. It is about the enduring human drive to explore, to test boundaries, and to transform the raw materials of nature into tools that shape civilizations. From copper smelters experimenting with hematite to modern scientists reanalyzing ancient slag, the chain of curiosity remains unbroken.

The Iron Age may have dawned thousands of years ago, but the spirit that made it possible is still with us today: the simple, powerful desire to ask, what happens if we try?

More information: Iron in copper metallurgy at the dawn of the Iron Age: Insights on iron invention from a mining and smelting site in the Caucasus, Journal of Archaeological Science (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2025.106338