Far to the north, where the great inland seas carve their way into the heart of North America, lies a narrow finger of land pointing defiantly into Lake Superior. This is Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, a place where the harsh breath of winter collides with the serene stillness of forests and waters. Beneath its rugged hills and rocky shores lies a secret that has drawn humans for thousands of years: copper. Unlike much of the world where copper must be pried from ore through smelting, the Keweenaw held veins of nearly pure native copper, glittering in raw metallic beauty, waiting to be unearthed.

The story of Michigan’s copper mines is not only about industry and geology but also about mystery. Long before the arrival of European settlers, ancient peoples dug into these lands, leaving behind pits and tools yet whispering little about their identity. Centuries later, waves of immigrants would descend into the dark shafts of industrial mines, their songs and struggles echoing through the tunnels. To walk the Keweenaw today is to walk on layered histories—some recorded, others still enigmatic.

The Ancient Miners of the Keweenaw

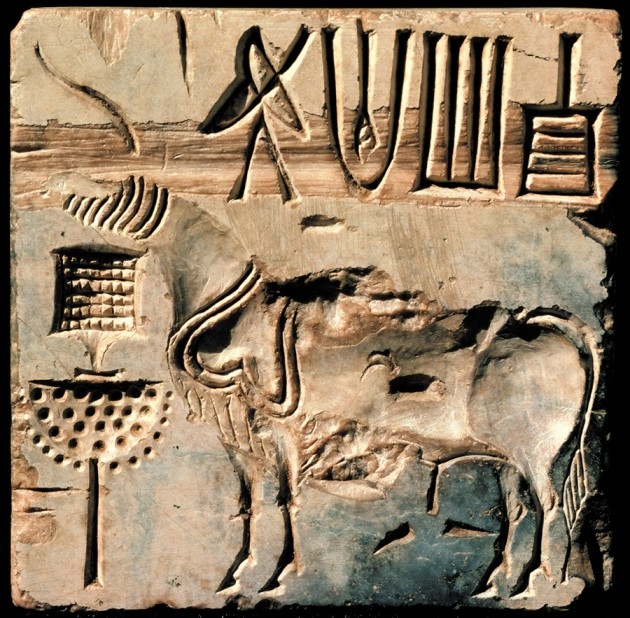

The first miners of Michigan’s copper were not wielding dynamite or steam-powered drills. Thousands of years ago, long before European contact, Native American cultures had discovered the copper veins. Archaeological evidence reveals that between 5,000 and 7,000 years ago, people were extracting copper using nothing more than stone hammers, fire, and persistence. They hammered and pried, sometimes lighting fires against rock faces and then dousing them with water to fracture the stone.

The evidence remains scattered across the peninsula—thousands of pits, now filled with soil and vegetation, but still recognizable to the trained eye. Hammerstones, often made of hard basalt, litter the sites. Some pieces of copper were pounded into tools and ornaments: awls, fishhooks, knives, and decorative beads. These artifacts, traded widely, have been discovered across North America, showing that the copper of Michigan traveled far beyond the Great Lakes.

And yet, the identity and fate of these miners remain shrouded in mystery. By the time Europeans reached the region in the 1600s, large-scale prehistoric mining had long ceased. Oral traditions among Indigenous groups remembered the copper but spoke little of the ancient diggers. Were they ancestors of the Ojibwe and other tribes of the region? Or a culture lost to time? Archaeologists continue to debate, their theories weaving possibilities but never settling on certainty. The silence of these ancient miners makes their presence all the more haunting.

The Coming of Industry

When Europeans finally turned their eyes to the Keweenaw in the early 19th century, they rediscovered what Native peoples had known for ages: the land was rich in copper. Early explorers marveled at chunks of native copper weighing hundreds of pounds, gleaming in riverbeds or protruding from hillsides. These were not the ordinary ores found in most of the world—this was copper so pure it could be shaped without smelting.

The 1840s sparked the first great copper rush. Prospectors swarmed into the peninsula, cutting paths through forests, staking claims, and founding mining towns. Companies soon followed, and shafts were sunk deep into the earth. Mines like the Quincy, the Calumet & Hecla, and the Copper Falls became legendary, producing staggering quantities of copper that fed America’s growing appetite for telegraph wires, plumbing, and eventually, electricity.

Life in the mining towns was harsh and often short. The work demanded long hours underground, in conditions dark, damp, and dangerous. Accidents were frequent, from collapsing tunnels to deadly gas. And yet, the mines beckoned workers from across the world. Immigrants arrived in waves: Cornish miners from England, Finns fleeing poverty, Italians, Irish, Germans, and many others. Each group brought not only labor but traditions, foods, and songs, weaving a multicultural tapestry in the isolated north.

The World Below

To descend into a Michigan copper mine was to enter another world. Imagine a shaft plunging deep into the earth, perhaps a mile below the surface, lined with timbers and echoing with the sound of picks, drills, and voices. Oil lamps or, later, carbide lamps flickered in the darkness, casting ghostly shadows across walls glittering faintly with metal.

Miners used hand drills and hammers in the early days, painstakingly creating holes for black powder charges. Later, mechanized drills and dynamite transformed the pace but also increased the risks. Air was stifling, humidity oppressive, and the ever-present fear of cave-ins hung like a shadow over every worker.

Despite the dangers, camaraderie flourished. Songs in Cornish or Finnish echoed through tunnels. Stories and superstitions took root. Some miners spoke of strange lights or whispers in the dark, perhaps hallucinations born of exhaustion, perhaps something more. For those who spent most of their waking hours underground, the mines became not just a workplace but a living, breathing entity—sometimes friend, often foe.

The Great Copper Boom

By the late 19th century, Michigan was producing more copper than any other place in the world. The Calumet & Hecla Mining Company became the titan of the industry, responsible for vast wealth and immense influence. Entire towns depended on the mines, and company policies shaped nearly every aspect of daily life.

But prosperity was not evenly shared. While company owners and investors grew rich, miners earned meager wages and endured brutal conditions. Labor unrest brewed, reaching its tragic climax in the 1913–1914 copper strike. Thousands of miners demanded fair wages and safer conditions, leading to bitter standoffs with company guards and the National Guard.

The strike’s darkest moment came during the Italian Hall disaster in Calumet on Christmas Eve, 1913. As striking miners and their families gathered for a holiday party, someone—unidentified to this day—shouted “fire!” A panic stampede ensued down the building’s narrow staircase. Seventy-three people died, most of them children. The tragedy became a scar on the region’s memory, a symbol of both the miners’ struggle and the human cost of industrial greed.

Decline of the Mines

As the 20th century unfolded, the copper mines of Michigan began to fade. Rich deposits were depleted, and global competition made the industry less profitable. The rise of open-pit mining in the western United States and abroad further eclipsed Michigan’s deep-shaft mines.

By the 1960s, most of the great mines had closed, leaving behind empty shafts, rusting equipment, and ghost towns. Families moved away, seeking work in cities or other industries. Those who remained watched as once-bustling communities shrank, their schools and shops shuttered.

Yet the legacy of the mines refused to vanish. Abandoned headframes and stamp mills still stand against the skyline, monuments to a past both triumphant and tragic. Beneath the forests, tunnels stretch for miles, silent now but filled with stories.

The Mysteries That Endure

Even with centuries of study and exploration, mysteries still cling to the copper mines of Michigan. The most tantalizing questions lie with the prehistoric miners. How did they extract such vast amounts of copper with only primitive tools? What became of their societies? Did they trade copper as far as South America, as some theories suggest, or is that legend born of speculation?

Within the industrial era, too, enigmas remain. Miners spoke of eerie experiences underground—strange sounds, ghostly figures, feelings of being watched. Some attributed these to the spirits of those who perished in accidents, others to the restless souls of the ancient miners themselves. Whether one views such tales as folklore or something more, they reflect the deep psychological weight of working in the earth’s dark, hidden places.

The Italian Hall disaster, too, retains its mysteries. Who shouted “fire”? Why was such panic so swift and deadly? Historians still debate the details, while locals preserve the memory as a cautionary tale of injustice and tragedy.

The Miners’ Legacy

Though the mines have closed, the spirit of the miners endures in the culture of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The descendants of those immigrants still gather for Finnish saunas, Cornish pasties, and Italian festivals. Stories of strikes, tragedies, and triumphs are passed down through generations. Museums and heritage sites preserve not only artifacts but the memory of those who labored in the depths.

More than just an industrial chapter, the copper mines shaped the identity of the region. They brought people from across the world to a remote peninsula and forced them to forge communities in the face of hardship. They left scars in the land and in memory, but also pride—a pride in endurance, resilience, and connection to a story bigger than any one life.

Copper and the Earth’s Memory

Geologically, the Keweenaw copper deposits are as unique as the human stories they inspired. They formed over a billion years ago, when ancient lava flows created the conditions for copper to crystallize in nearly pure form. Nowhere else on Earth has such vast native copper been found.

To hold a piece of Keweenaw copper is to hold Earth’s memory in your hand. It is metal forged in fire, shaped by time, and uncovered by human hands spanning millennia. It is both ordinary and extraordinary—ordinary as plumbing pipes and electrical wires, extraordinary as a bridge between ancient miners and modern engineers.

The Echo of the Mines Today

Today, the copper mines of Michigan are quiet. Forests reclaim the land, wildlife roams where stamp mills once thundered, and shafts are sealed to prevent collapse. Yet the echo of the mines lingers. Heritage sites like the Quincy Mine or the Keweenaw National Historical Park invite visitors to step into the past, donning hard hats and riding trams into cool underground chambers. There, guides tell stories of miners and mysteries, of triumphs and tragedies.

For locals, the mines are more than history—they are identity. They are the reason their ancestors came, the foundation of their communities, and the source of both sorrow and pride. For visitors, the mines are a reminder of how deeply human lives intertwine with the land, how the hunger for resources drives both innovation and suffering.

Conclusion: A Legacy Written in Stone and Blood

The copper mines of Michigan are a paradox: a story of prosperity and poverty, of discovery and loss, of clarity and mystery. From the silent pits of ancient miners to the roaring engines of industrial shafts, from the joy of community gatherings to the sorrow of disasters, the Keweenaw’s copper story is human history in microcosm.

In the end, the mysterious miners—ancient and modern—share a common bond. They all descended into the earth, searching for something that gleamed in the darkness. They all risked their lives in pursuit of a metal that shaped tools, connected continents, and electrified the world. And they all left behind more than copper—they left behind stories, whispers in stone, waiting for those who come after to listen.

The Keweenaw Peninsula stands today as a quiet memorial to those lives. Its forests grow thick, its lakes shimmer, and its mines lie silent. But beneath the surface, in the imagination of those who still wonder, the miners remain.