Long before towering empires, before the gleam of pyramids or the glory of Rome, there was a land nestled between two great rivers. Mesopotamia—literally “the land between rivers” in Greek—has long been called the birthplace of civilization. It was here, thousands of years ago, that humanity took some of its boldest steps forward: inventing writing, building cities, establishing laws, and shaping culture in ways that still echo in our lives today.

This land, lying in the fertile valley between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, is more than a geographic region. It is the stage where human history transformed from scattered villages into complex societies. It is where myths of creation, kingship, and divine authority were first carved into clay. To explore Mesopotamia is not only to understand the past but also to witness the moment humanity began to tell its own story.

Geography: Land Between Rivers

Mesopotamia stretched across a fertile plain located in present-day Iraq, along with parts of Syria, Turkey, and Iran. Unlike deserts or mountainous regions, this landscape was cradled by rivers that carried life-giving waters from distant highlands. The Tigris and Euphrates did not just nourish crops; they shaped the rhythm of existence. Their floods could be unpredictable—sometimes gentle, sometimes destructive—but always vital.

This geography created both challenges and opportunities. The soil, replenished by silt from seasonal floods, yielded abundant harvests when carefully managed. Irrigation systems—canals, ditches, and levees—were constructed to tame the rivers and extend agriculture into drier lands. This abundance of food enabled population growth, urban development, and specialization of labor, laying the foundation for the world’s first cities.

Mesopotamia’s open plains also made it vulnerable to invasion. With few natural barriers, the region became a crossroads where different peoples mingled, traded, and fought. Over millennia, Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians all rose and fell here, leaving behind legacies that would shape civilization itself.

The Dawn of Cities

The most remarkable achievement of Mesopotamia was the birth of the city. Around 4000 BCE, small agricultural villages in southern Mesopotamia grew into thriving urban centers. By 3000 BCE, cities like Uruk, Ur, Lagash, and Eridu had emerged, with populations numbering in the tens of thousands.

Uruk, often considered the world’s first true city, became a symbol of this transformation. Its massive walls, monumental temples (ziggurats), and sprawling neighborhoods reflected a society that had moved beyond survival into cultural and political organization. Specialization of labor meant that not everyone needed to farm; artisans, priests, merchants, and scribes flourished, supported by agricultural surplus.

These cities were not only centers of trade and governance but also places of innovation. In the temples of Uruk, priests kept records of offerings, leading to the invention of writing. In the workshops, metals were smelted, pottery was fired, and wheeled carts were built. In the palaces, kings declared laws and legitimized their power through divine association.

Writing: The Voice of Civilization

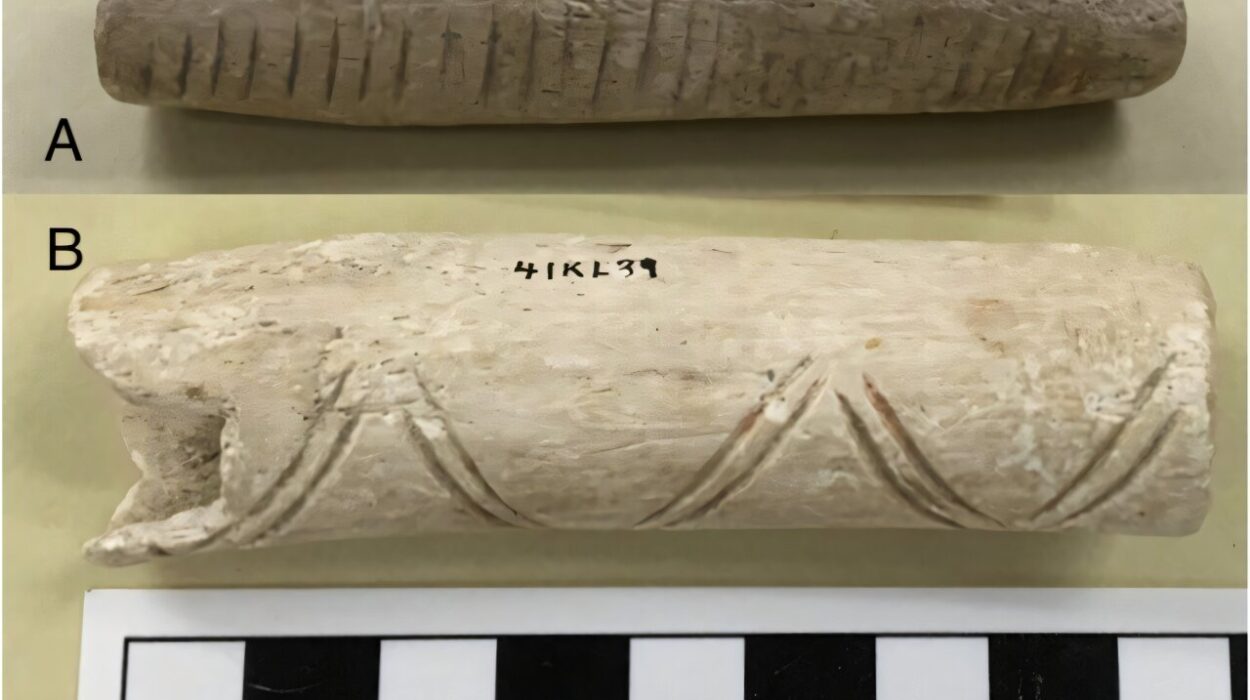

Among all Mesopotamia’s contributions, none is more transformative than writing. Around 3200 BCE, scribes in Sumer developed cuneiform, a system of wedge-shaped impressions pressed into clay tablets with a reed stylus. What began as simple marks to track goods and transactions soon blossomed into a versatile script capable of recording myths, laws, letters, mathematics, and literature.

Writing changed everything. It allowed rulers to issue decrees, merchants to keep accounts, priests to preserve hymns, and storytellers to immortalize epics. The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of humanity’s oldest works of literature, was inscribed on clay tablets in cuneiform. It told of kings, gods, and the search for immortality—revealing not only Mesopotamian imagination but also universal human concerns about life, death, and meaning.

Cuneiform spread beyond Sumer, adapted by Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, becoming the lingua franca of diplomacy and trade across the ancient Near East. It marked the dawn of history, for once humans could record their thoughts, memory no longer faded with each generation. Civilization had found its voice.

Kings, Priests, and the Rise of Authority

In Mesopotamia, power was woven from the threads of religion and politics. The earliest cities were often ruled by priest-kings, who combined spiritual and administrative authority. Temples, known as ziggurats, dominated the urban skyline, serving not only as places of worship but also as economic centers, storing grain, managing trade, and organizing labor.

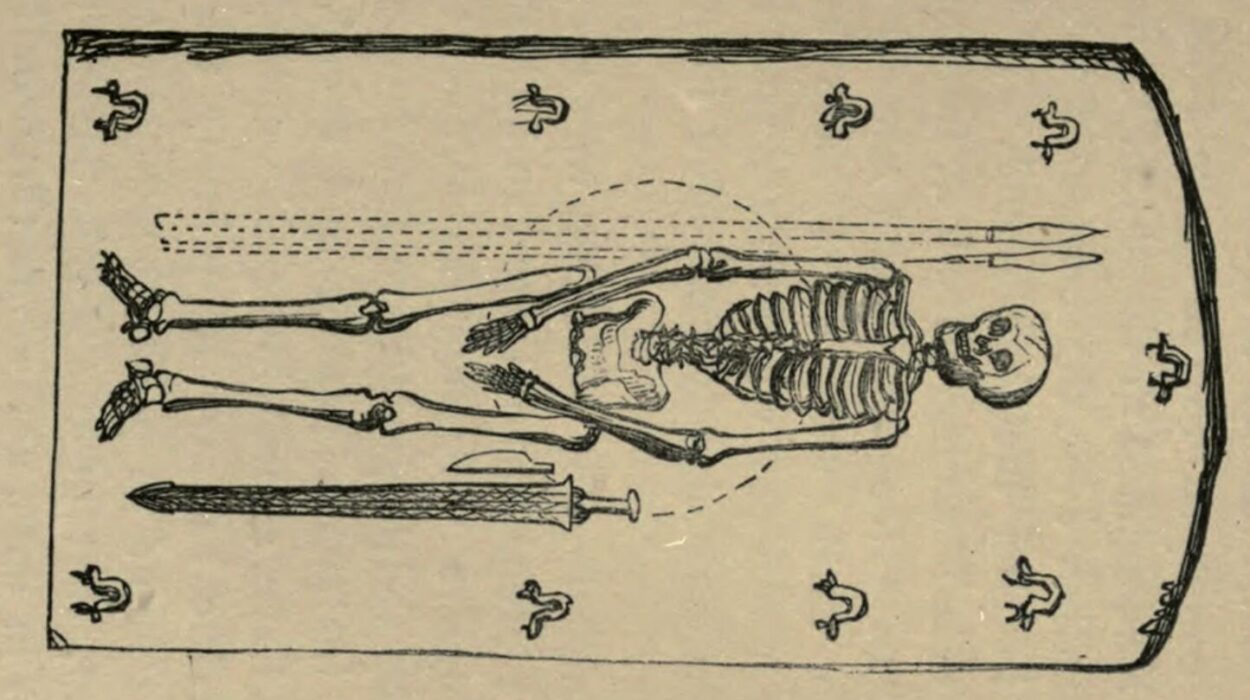

As cities grew and conflicts emerged, military leaders rose to prominence, eventually establishing dynasties of kings. These rulers often justified their authority through divine sanction, claiming to be chosen by the gods. Hammurabi of Babylon, for instance, presented his famous code of laws as handed down from Shamash, the sun god of justice.

The Code of Hammurabi, inscribed on a stone stele around 1754 BCE, stands as one of the earliest and most complete legal codes. It defined laws concerning trade, marriage, property, and crime, guided by the principle of justice—though stratified by social class. It was a recognition that society required rules, not just power, to function.

Gods and Myths: A Divine Landscape

Religion permeated every aspect of Mesopotamian life. The people believed their world was governed by a pantheon of gods, each controlling forces of nature and human destiny. Anu was the sky god, Enlil ruled the winds and storms, Inanna (Ishtar) embodied love and war, and Marduk, later the chief deity of Babylon, represented order and kingship.

Myths explained the unpredictable floods, the cycles of crops, and the fragility of human life. Creation stories, such as the Enuma Elish, described how gods formed the world from chaos. Humanity, according to many myths, was created to serve the gods, to provide offerings and maintain temples.

The religious imagination of Mesopotamia gave rise to rituals, festivals, and monumental architecture. Ziggurats, towering stepped pyramids, were designed as bridges between earth and heaven. Priests interpreted omens from the stars, the liver of sacrificed animals, or the flight of birds, seeking divine guidance for kings and communities.

Trade, Technology, and Everyday Life

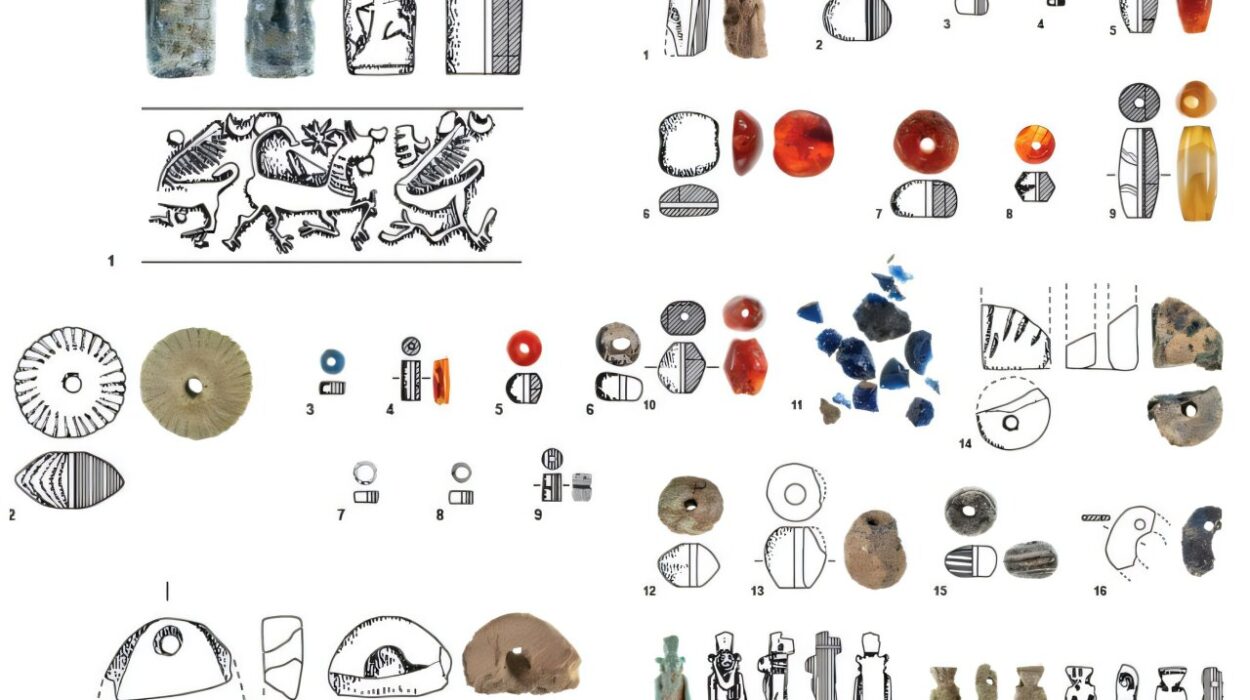

Beyond temples and palaces, Mesopotamian civilization thrived on the daily lives of its people. Farmers cultivated barley, wheat, and dates, supported by irrigation systems. Shepherds tended flocks of sheep and goats, providing wool, milk, and meat. Fishermen cast their nets into the rivers, while craftsmen shaped clay into pottery, bronze into tools, and stone into statues.

Trade networks extended across the ancient world. Lacking natural resources like timber and metals, Mesopotamians imported cedar from Lebanon, copper from Oman, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, and gold from Egypt. In return, they exported textiles, grain, and crafted goods. The rivers served as vital highways, connecting cities and facilitating exchange.

Homes of ordinary people were built of sun-dried mudbrick, simple yet functional. Families lived in close-knit households, with women playing active roles in managing property, brewing beer, and participating in trade. Children were taught practical skills, though the sons of elites could train as scribes in temple schools, mastering the demanding art of cuneiform.

The Rise and Fall of Empires

Mesopotamia’s history is marked by cycles of unity and fragmentation, as city-states gave way to empires and empires collapsed under the weight of new conquerors.

The Sumerians laid the foundation with their city-states and inventions. Around 2334 BCE, Sargon of Akkad created the world’s first empire, uniting Mesopotamia under Akkadian rule. His dynasty established patterns of imperial administration that would echo for centuries.

The Akkadians gave way to the Babylonians, whose most famous king, Hammurabi, left a legacy of law. Later, Assyria rose in the north, building a militaristic empire that stretched from Egypt to Persia, feared for its conquests but admired for its administrative innovations and libraries. The library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh preserved thousands of clay tablets, ensuring Mesopotamian knowledge survived into later ages.

Babylon experienced a renaissance under Nebuchadnezzar II in the 6th century BCE, renowned for its grandeur and the legendary Hanging Gardens. Yet soon after, Mesopotamia was absorbed into larger empires—the Persians, the Greeks under Alexander, and eventually the Romans. The cradle of civilization became part of the wider tapestry of world history, but its achievements endured.

Science, Mathematics, and Astronomy

Mesopotamians were not only farmers and builders but also scientists and thinkers. Their observations of the heavens led to early forms of astronomy. They mapped the movements of stars and planets, creating calendars that guided agriculture and ritual. Their fascination with celestial omens intertwined science with divination, but their systematic records laid groundwork for later astronomy in Greece and beyond.

In mathematics, they developed a base-60 system, which survives today in our division of time into 60 minutes and 60 seconds, and in the 360 degrees of a circle. They used multiplication tables, solved quadratic equations, and calculated areas of land—practical knowledge that also reflected abstract thought.

Medical texts reveal treatments for diseases, using both herbal remedies and incantations. While often mixed with magic, their medical practices demonstrated an empirical approach to observation and healing. Mesopotamian science was a blend of the mystical and the rational, a reminder that the pursuit of knowledge was inseparable from the quest for meaning.

Legacy of Mesopotamia

Though the cities of Mesopotamia eventually fell into ruin, their influence never vanished. From writing to law, from urban life to empire, the innovations of Mesopotamia became the inheritance of the ancient world. The Hebrews, Persians, Greeks, and Romans all encountered and absorbed elements of Mesopotamian culture, passing them along to later civilizations.

Even today, echoes of Mesopotamia shape our world. Our clocks and calendars bear traces of their mathematics. Our legal systems descend from the recognition that laws must govern society. Our literature continues to draw upon myths like the Epic of Gilgamesh, whose themes of friendship, mortality, and the search for meaning remain timeless.

Most importantly, Mesopotamia reminds us of humanity’s capacity to create order from chaos, to build communities, and to imagine gods, laws, and stories that give life significance. It is a reminder that civilization is not a given but a fragile achievement, born of cooperation, imagination, and the constant struggle to survive and thrive.

Conclusion: The Eternal Cradle

Mesopotamia is often called the cradle of civilization, and rightly so. It was here that humanity first experimented with cities, writing, law, and empire. It was here that myths were told, stars were mapped, and clay tablets recorded the dreams and anxieties of the world’s first urban societies.

But Mesopotamia is more than a place on a map or a chapter in a textbook. It is the story of how human beings, faced with the challenges of rivers, floods, and open plains, dared to build something enduring. It is the story of our ancestors’ first attempts to understand the world, to organize society, and to leave a legacy.

Though the rivers have shifted and the cities have crumbled into dust, the spirit of Mesopotamia lives on—in every written word, every city skyline, every law that shapes our daily lives. To remember Mesopotamia is to remember where we began—not just as scattered tribes, but as a civilization.