Long before the rise of the Maya’s astronomical cities or the Aztecs’ mighty empire, a mysterious civilization thrived along the swampy lowlands of the Gulf Coast of present-day Mexico. Known today as the Olmecs, they are often called America’s first great culture. Yet, despite their monumental achievements, much of their world remains cloaked in mystery. Who were they? What did they believe? How did they shape the civilizations that followed?

The Olmecs are enigmatic not because they left behind little, but because they left behind things so astonishing, so advanced, that historians, archaeologists, and everyday people still marvel at them today. Towering stone heads with human-like features, sophisticated artwork, intricate religious systems, and possible early writing—all emerged from this culture, which flourished from about 1600 BCE to 400 BCE. The Olmecs stand at the dawn of Mesoamerican civilization, pioneers whose influence radiated outward for centuries.

To walk among the ruins of San Lorenzo or La Venta is to feel the presence of a people who lived in harmony with rivers and swamps, who gazed into the stars, who carved their rulers’ faces into stones weighing dozens of tons. Their legacy still whispers through the jungles of Tabasco and Veracruz, reminding us that history’s greatest stories often begin with a question: How could such a civilization rise so early, and why did it vanish?

The Birthplace of the Olmecs

The Olmec heartland stretched across the hot, humid lowlands of southern Veracruz and northern Tabasco, where rivers like the Coatzacoalcos, Tonalá, and Papaloapan snaked through lush landscapes. This environment was both a blessing and a challenge. Dense swamps and thick forests made travel difficult, yet the fertile soils and abundant waters provided the foundation for agriculture, fishing, and trade.

It was in this setting—harsh, yet bountiful—that the Olmecs built their culture. Around 1600 BCE, small farming villages began cultivating maize, beans, squash, and cacao. These crops formed the dietary and economic backbone of the civilization. Over generations, agricultural abundance fueled population growth, which in turn demanded political organization, religious systems, and cultural innovation.

By 1200 BCE, the Olmecs had established their first great ceremonial center: San Lorenzo. From here, their influence spread across Mesoamerica, like ripples from a stone dropped into water.

The Colossal Heads: Faces in Stone

Perhaps nothing defines the Olmecs more vividly than their colossal stone heads. Ranging from six to twelve feet in height and weighing up to fifty tons, these monumental sculptures depict human faces—broad-nosed, thick-lipped, stern-eyed, wearing what appear to be helmet-like headdresses.

The heads were carved from massive basalt boulders transported from the Tuxtla Mountains, sometimes over 50 miles away. Moving such enormous stones without wheels, beasts of burden, or advanced metal tools remains one of the great logistical feats of the ancient world. Scholars believe the heads represent Olmec rulers, immortalizing their likenesses in stone as enduring symbols of power.

Each head is unique, suggesting they may portray specific individuals rather than generalized deities. To stand before one is to feel the weight of authority and the mystery of identity—these were not anonymous figures but once-living people who ruled, who commanded, who were remembered. The colossal heads are not only masterpieces of art but also monuments to leadership, memory, and human ambition.

The Sacred and the Supernatural

Like many ancient cultures, the Olmecs lived in a world infused with the sacred. They developed one of the earliest pantheons of Mesoamerica, with gods linked to natural elements—rain, earth, maize, and jaguars. The jaguar, in particular, was central to Olmec religion. Fierce, elusive, and powerful, the jaguar embodied both earthly might and supernatural potency.

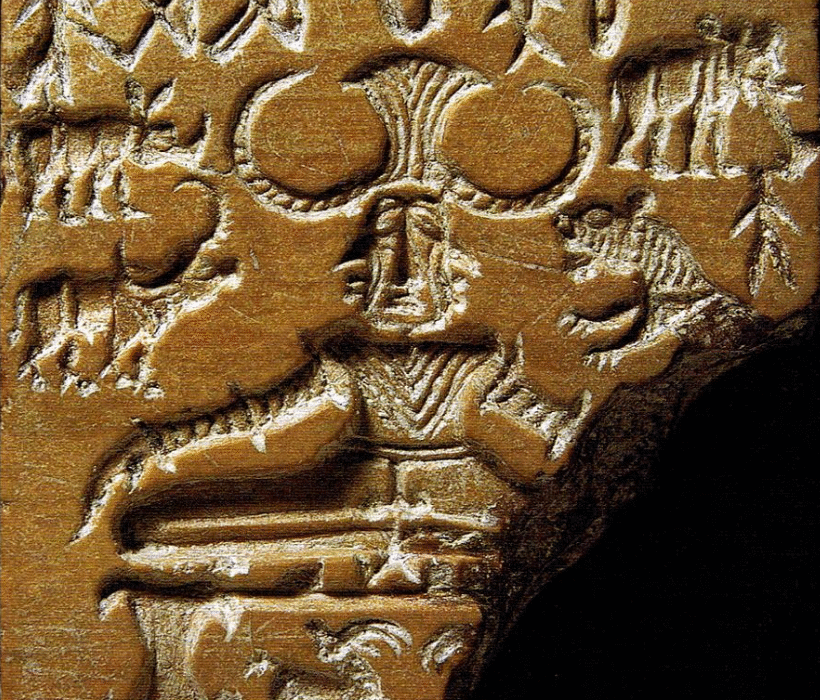

Olmec art often depicts human-jaguar hybrids, sometimes called the “were-jaguar.” These figures, with their downturned mouths and almond-shaped eyes, appear in sculptures, figurines, and carvings. Scholars debate their meaning: were they gods, shamans in trance, or mythical ancestors? What is certain is that the jaguar was a bridge between the natural and spiritual worlds.

The Olmecs were also among the first in Mesoamerica to build ceremonial centers aligned with astronomical events. Their pyramids, plazas, and altars were not random constructions but part of a cosmic order, connecting the earthly to the celestial. Rituals likely involved bloodletting, offerings, and perhaps even human sacrifice, as later cultures in the region practiced. For the Olmecs, religion was not separate from daily life—it was life’s very rhythm.

San Lorenzo: The First Great City

San Lorenzo, flourishing between 1200 and 900 BCE, was the first major Olmec center. Built on a plateau above the surrounding floodplains, it was not just a city but a ceremonial hub, an administrative seat, and a showcase of Olmec ingenuity.

Archaeologists have uncovered colossal heads, thrones, and intricate drainage systems at San Lorenzo. Yes, drainage systems—stone-lined channels that managed water across the site, a remarkable feat of early engineering. The city’s layout reflects careful planning, with plazas, mounds, and elite residences dominating the landscape.

San Lorenzo’s rise marked the beginning of Olmec cultural influence across Mesoamerica. Its decline around 900 BCE, perhaps due to environmental changes or social upheaval, paved the way for a new center: La Venta.

La Venta: The Sacred Capital

La Venta, located on an island in a swamp, emerged as the Olmecs’ second great center, flourishing from 900 to 400 BCE. It was here that the Olmecs refined their religious and political systems. The site’s core included a massive pyramid, nearly 100 feet tall, made entirely of earth. This pyramid is one of the earliest monumental constructions in the Americas, a precursor to the great pyramids of the Maya and Aztecs.

La Venta’s ceremonial layout reveals a strong sense of cosmology. Altars carved with intricate designs suggest rulers engaged in rituals connecting them to the spiritual world. Burials containing jade offerings—jade being more precious than gold to the Olmecs—indicate an elite class with access to exotic trade goods.

One of La Venta’s most intriguing discoveries is a mosaic floor made of thousands of serpentine blocks, carefully arranged into symbolic designs and then deliberately buried. Why create such an artwork only to hide it beneath the earth? Some scholars believe it was an offering to the gods, an eternal message concealed within the soil.

The Language of Symbols

The Olmecs may have been the first in the Americas to develop a system of writing. Archaeological finds, such as the Cascajal Block—a serpentinite slab engraved with glyph-like symbols—suggest an early script dating to around 900 BCE. While not fully deciphered, these symbols indicate an effort to record language, events, or rituals.

In addition to proto-writing, the Olmecs likely developed the Mesoamerican calendar system that would later be refined by the Maya. Their knowledge of astronomy, mathematics, and timekeeping reflects a deep engagement with the cycles of nature and the heavens.

The Olmecs were also masters of visual communication. Their art, whether in jade figurines, ceramic vessels, or monumental stone carvings, conveyed complex ideas about power, spirituality, and identity. To hold a small Olmec jade figure in one’s hand is to grasp a piece of their worldview—delicate, precise, meaningful.

Olmec Society and Daily Life

Beneath the grandeur of colossal heads and pyramids lived the everyday Olmecs—farmers, artisans, traders, and families. Most Olmecs lived in small villages, cultivating maize and other staples. Fishing and hunting supplemented their diet, while cacao may have been used as both food and currency.

Society was likely hierarchical, with powerful rulers and priests at the top, supported by skilled artisans who produced jade, obsidian, and ceramic goods. The colossal heads themselves suggest a society capable of organizing massive labor forces, indicating centralized authority.

The Olmecs were also great traders. Their influence reached far beyond their heartland, evidenced by Olmec-style artifacts found in regions as distant as Central Mexico and the Pacific coast. Through trade, they spread not only goods but also ideas—artistic styles, religious symbols, and perhaps even political models.

The Olmec Legacy

Though the Olmec civilization declined around 400 BCE, their cultural legacy lived on. The Maya, Zapotecs, and Aztecs all inherited elements of Olmec religion, art, and political organization. The sacred ballgame, played with a rubber ball in ritualized courts, traces its earliest evidence to the Olmecs. Their jaguar deities evolved into later Mesoamerican gods. Their calendar and perhaps their writing system seeded the intellectual achievements of the Maya.

The Olmecs were the “mother culture” of Mesoamerica, laying foundations upon which later civilizations built towering achievements. Yet, unlike their successors, the Olmecs remain enigmatic. No great chronicles of their kings survive, no long inscriptions tell us their stories. Their memory endures through stone, jade, and earth.

Mysteries Yet Unsolved

Despite decades of study, many questions about the Olmecs remain unanswered. Why did San Lorenzo and La Venta decline? Were natural disasters, climate change, or internal conflicts to blame? Who were the individuals immortalized in the colossal heads? Were they kings, warriors, or even ballplayers? Did the Olmecs truly invent writing, or were their symbols proto-scripts?

These mysteries fuel both academic debates and popular imagination. Some fringe theories—unsupported by evidence—suggest connections between the Olmecs and distant cultures in Africa or Asia, often citing the features of the colossal heads. Mainstream archaeology, however, firmly situates the Olmecs within the indigenous development of Mesoamerica. Their achievements were the product of their own environment, creativity, and vision.

Conclusion: The First Great Culture of the Americas

The Olmecs were more than a vanished people; they were pioneers. They rose from the swamps of Veracruz and Tabasco to create a civilization that shaped the destiny of Mesoamerica for centuries. Their colossal heads, sacred symbols, and mysterious rituals stand as testaments to human ingenuity and spirituality.

To study the Olmecs is to peer into the dawn of American civilization, to see the first sparks of ideas that would later blaze in the cities of the Maya and the empires of the Aztecs. They remind us that greatness does not always leave written records or grand ruins—it sometimes lingers in stone faces staring silently through the ages.

The Olmecs remain a riddle, but one filled with beauty, wonder, and significance. Their world invites us not only to ask who were they but also to reflect on the deeper question: how does culture begin, grow, and echo across time? In that sense, the Olmecs are not only America’s first great culture—they are humanity’s timeless reminder that every civilization begins with vision, courage, and mystery.