In the hushed and climate-controlled vaults of the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of the University of Turin, Italy, the silent witness of an ancient civilization lay undisturbed for decades. She had been found high in the Andes, preserved by the cold and the dry mountain air—her identity unknown, her story long buried beneath layers of time and soil. But thanks to an international team of anthropologists, cultural heritage experts, and laboratory scientists, this 800-year-old Andean mummy is speaking again—this time, through the language of ink.

A Whisper from the Andes

The woman, estimated to have lived between 1215 and 1382 CE during a time of vast sociopolitical change in the pre-Inca Andes, represents a rare and precious window into the lives, beliefs, and practices of Indigenous South American cultures. Her remains were remarkably preserved, but it wasn’t just her state of conservation that caught the attention of researchers—it was what her skin might be hiding.

In the realm of archaeology, tattoos are a fragile treasure. Soft tissue decays quickly under most burial conditions, and even when preserved, the pigments used in ancient tattoos often fade or vanish entirely. But with modern imaging techniques and chemical analyses, the research team hoped to uncover what time had hidden.

And what they found was unlike anything seen before.

Ink Beneath the Skin: A Technological Excavation

The team began by verifying the mummy’s age through radiocarbon dating, pinning her lifetime to the centuries before the Spanish arrival in South America. This was a period characterized by the rise of powerful states like the Chimú and the expanding influence of the Inca. The region was a mosaic of rich, interlocking cultures with distinct traditions and symbolic systems—including, apparently, tattooing.

But unlike the elaborate geometric tattoos found on some mummified individuals from the Chinchorro or Nazca cultures, these tattoos were elusive. To the naked eye, her skin appeared unmarked.

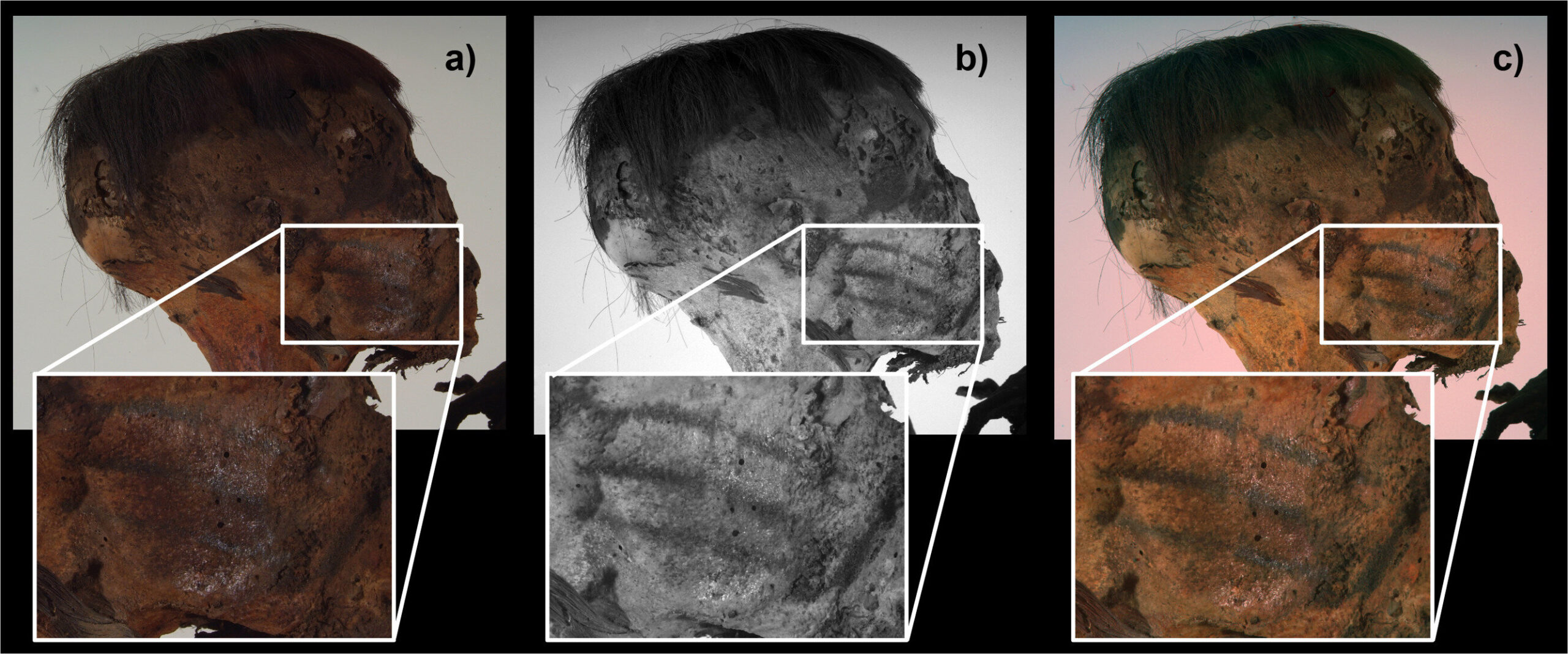

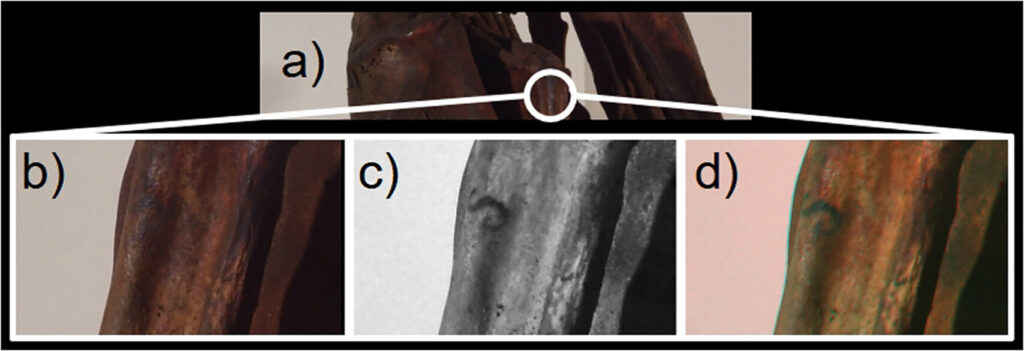

That’s where technology stepped in. The researchers deployed infrared false-color analysis ranging from 500 to 950 nanometers, followed by 950-nm wavelength band infrared reflectography. These non-invasive imaging techniques allow researchers to peer below the surface of skin, revealing patterns that are otherwise invisible.

What they found was astonishing.

On each cheek, three slender, vertical lines traced a subtle path from the ear toward the mouth. Stark in their simplicity, they hinted at a deliberate aesthetic or symbolic choice. And on her right wrist, an “S”-shaped mark curved gracefully, distinct in form and unlike any previously documented tattoo from Andean mummies.

These markings—delicate, discreet, and deeply deliberate—pose more questions than they answer.

Pigment of the Past: What Was in the Ink?

The discovery of the tattoos sparked an equally pressing question: What were they made of? The inks used by ancient tattoo artists can reveal much about the culture’s technological capabilities, trade networks, and symbolic systems. Traditionally, most archaeological examples of tattoo ink include charcoal, often mixed with plant resins or animal fats. But in this case, the team found something far more unexpected.

To unlock the chemical composition of the pigments, they turned to X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, μRaman spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM)—tools more commonly associated with material science and forensic analysis than with anthropology.

The results defied expectations.

The pigments embedded in the woman’s skin were made from magnetite, an iron oxide mineral, and pyroxenes, a class of silicate minerals commonly found in igneous rocks. Notably absent was charcoal, the near-universal base for ancient tattooing inks. This unusual composition suggested that these tattoos weren’t merely decorative—they were made using materials likely chosen for their specific properties or meanings.

Magnetite, for example, is magnetic and was used in ritual contexts across the ancient world. Pyroxenes, formed under intense volcanic conditions, might have held cosmological significance in a culture where mountains were sacred and geological phenomena were attributed to divine forces.

Could these minerals have held spiritual or ceremonial value? Or were they simply practical choices from a mineral-rich environment? Either way, their use speaks to a level of innovation and intentionality that redefines what we thought we knew about tattooing in the Andes.

A Tattooed Enigma: Who Was She?

While the inked patterns are now clear, the woman herself remains an enigma. Her facial tattoos, placed so visibly on either cheek, suggest a status or role that was both public and important. Facial tattoos are not common in Andean mummy finds; most documented tattoos from the region are found on limbs or torsos. To mark the face—so prominently and permanently—was likely a statement of identity.

But what kind of identity?

Was she a priestess, a healer, or a medium between worlds? Did these marks signify marital status, tribal affiliation, or achievements? Could they have been protective symbols meant to guide her in the afterlife? Or perhaps, were they part of a rite of passage, a transition from one stage of life to another?

The S-shaped wrist tattoo is equally enigmatic. Spirals and curves often symbolize cycles of life, rivers, or serpents in Indigenous iconography. But without a direct cultural analog, interpretations remain speculative.

The uniqueness of these tattoos makes them all the more fascinating. No other mummy from the region, or the period, bears tattoos of the same form or in the same location. It’s possible this woman belonged to a distinct subgroup, a marginal community, or an elite order with esoteric rituals lost to time.

The Art and Anthropology of Skin

Beyond its immediate archaeological value, this discovery underscores the importance of tattoos as cultural texts—intimate records of individual and communal identity etched into the body. Tattooing is one of humanity’s oldest art forms, with documented evidence going back at least 5,300 years, as seen in Ötzi the Iceman. But every region developed its own tattooing lexicon, and every culture used ink to speak in its own symbolic language.

In the Andes, where textiles, pottery, and stonework are often highlighted as dominant art forms, tattooing has been relatively underexplored. That’s partly due to the lack of preserved skin and partly due to disciplinary focus. But as this study demonstrates, the skin itself is a canvas—and sometimes, it’s the only surviving artifact of an individual’s inner world.

By decoding the ink, scientists are also decoding cultural memory, spirituality, and identity.

Technologies of Revelation

The study also reflects the growing power of interdisciplinary research in heritage science. The combination of anthropology, chemistry, imaging technology, and cultural heritage conservation has opened up new frontiers in understanding the past.

Without damaging the mummy or taking invasive samples, researchers were able to “see” beneath the skin and analyze ancient pigments at the molecular level. What once might have taken destructive methods—or remained invisible altogether—can now be uncovered safely and with incredible detail.

This approach is becoming increasingly vital in a world where the preservation of cultural artifacts and ethical handling of human remains are paramount. The Turin mummy represents a model case: science in service of memory, rather than destruction.

In the Shadow of the Andes, New Questions Rise

Even as the study answered one question—are there undiscovered tattoos on this mummy?—it opened a dozen more. Why these minerals? Why the face? Why now, in that particular moment of Andean history?

The researchers, in their published paper in the Journal of Cultural Heritage, do not attempt to impose conclusions. Instead, they invite further exploration, suggesting that this might be the tip of the iceberg. Could other mummies, previously examined only with the naked eye, also bear invisible tattoos? Might whole traditions of tattooing in the Andes have gone unnoticed, literally hiding in plain sight?

And if so, what other ancient stories are waiting to be revealed—not in bones, or ceramics, but in the ink preserved beneath the skin?

Conclusion: A Silent Story Brought to Light

In the quiet dark of the Turin museum, the woman from the Andes no longer lies entirely silent. Thanks to the dedication of an international team, and the delicate interplay between modern science and ancient mystery, a fragment of her life has been restored.

Her tattoos—deliberate, permanent, and deeply personal—speak across eight centuries. We may never know her name, but her marks remain: testimony to a vanished world, a forgotten art, and a culture that understood something we’re just beginning to rediscover.

The human body, even in death, is not merely a vessel. It is a document. And sometimes, all it takes to read it is the right kind of light.

Reference: Gianluigi Mangiapane et al, Rare tattoos shape and composition on a South American mummy, Journal of Cultural Heritage (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.culher.2025.04.013