In 1958, an amateur archaeologist named John Cowles stepped into Cougar Mountain Cave in Oregon and began to dig. What he uncovered did not immediately rewrite history. Instead, the artifacts he collected were carefully kept, eventually finding a home at the Favell Museum in Klamath Falls after his death in the 1980s. For decades, they waited quietly.

Now, modern archaeologists have returned to those long-shelved objects with new tools and sharper questions. Alongside artifacts from the nearby Paisley Caves, they have pieced together a story that feels at once intimate and profound. Their findings, published in Science Advances, offer a rare glimpse into how humans survived one of the most dramatic climate shifts of the Late Pleistocene.

The Cougar Mountain Cave and Paisley Caves are not ordinary archaeological sites. They are time capsules. Their desert-like environment preserved fragile, organic materials that would normally decay and vanish. In most places, ancient fiber and hide dissolve into nothing. Here, they endured for more than twelve thousand years.

When the World Suddenly Turned Cold

The artifacts from these caves mostly date to around 12,000 years ago, during a period known as the Younger Dryas. It was a time of abrupt cooling, when temperatures dropped after a relatively warmer stretch. The climate shifted, and with it, the rules of survival.

For years, research into this era focused heavily on big-game hunting. Spears, projectile points, and the pursuit of large animals dominated the story of early human life. Yet something was missing. Perishable materials—items made from plant fibers, hides, and other organic substances—rarely survived the ages. Without them, a large part of daily life remained invisible.

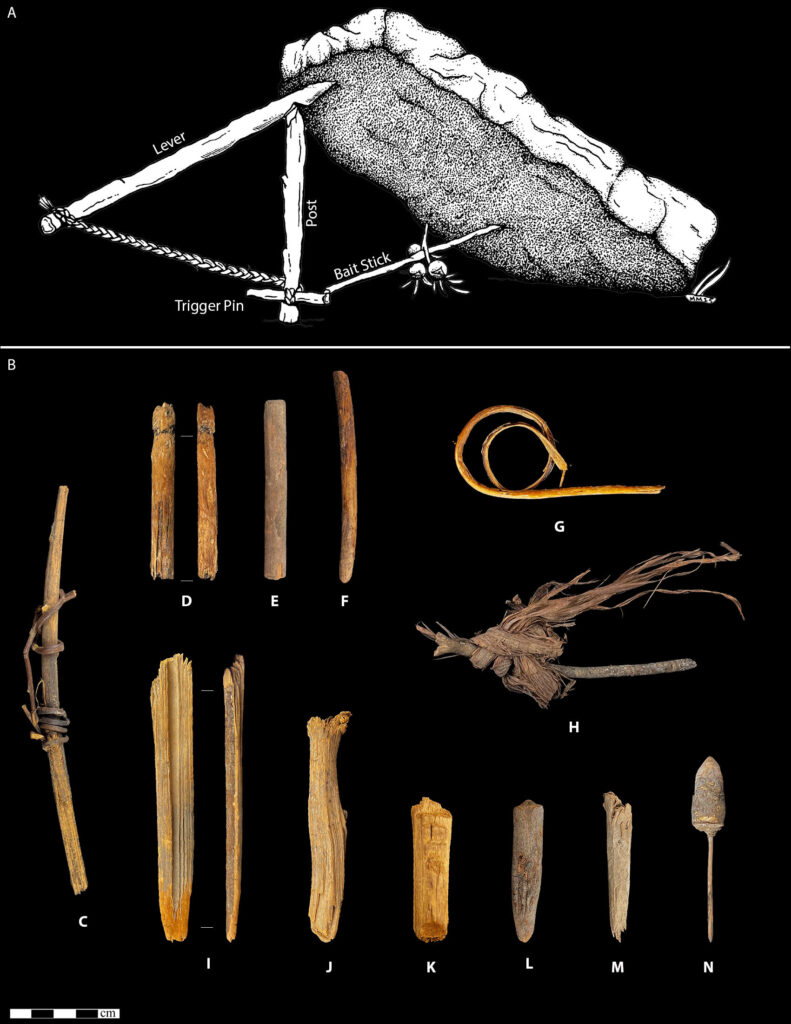

But in central Oregon’s caves, the dry conditions protected what is usually lost. Ancient fiber cordage, strips of hide, wooden trap components, and bone tools lay preserved. And among them was something extraordinary: the oldest piece of sewn material ever found.

A Fragment That Speaks Across Millennia

The artifact, labeled CMC21-1, is a fragment of processed and dehaired elk hide. At first glance, it might seem unremarkable—a torn piece of ancient leather. But closer inspection reveals remarkable detail.

Sewn into its margin is a Zss cord, made from a mixture of monocot plant fiber and animal hair. The cord exits the edge of the larger hide fragment and extends into a smaller piece of hide, where it is knotted carefully to prevent it from pulling free.

This was not a loose draping of fur over shoulders. This was deliberate, precise work.

Researchers interpret the fragment as the margin of a tight-fitting item—perhaps clothing, a moccasin, a bag, a container, or even part of a portable shelter. While they cannot say with absolute certainty that it was clothing, its construction suggests careful tailoring.

Tight-fitting garments matter in cold climates. Loose hides wrapped around the body offer some protection, but they allow cold air to slip through. Sewing changes everything. A stitched seam closes gaps, traps warmth, and allows for movement without sacrificing insulation. With the help of bone needles, people could create clothing that moved with their bodies while shielding them from bitter air.

The sewn elk hide dates to approximately 12,600–12,050 calibrated years before present, placing it squarely within the Younger Dryas. It is a quiet but powerful testimony to human adaptation during a time of environmental stress.

The Science of Time and Identity

To understand these objects fully, researchers turned to modern analytical methods. They used radiocarbon dating to determine age, Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS) to identify animal species from collagen, and taxonomic identification to classify plant and animal remains.

In total, they gathered 66 radiocarbon dates on 55 items representing 15 plant and animal taxa. The results showed that the collection dated between about 12,100 and 11,000 calibrated years before present.

These numbers do more than mark time. They anchor the artifacts to a specific climatic moment. They confirm that these sewn and woven technologies emerged during a sudden cold snap. The timing is not coincidence. It is context.

Sewing Survival Into Every Seam

The appearance of sewn materials during the Younger Dryas hints at something deeper than technical skill. It reveals ingenuity born of necessity.

When temperatures fall and the risk of hypothermia rises, survival demands innovation. Loose coverings may no longer suffice. The solution, in this case, seems to have been tighter, sewn clothing that sealed warmth in and kept freezing air out.

Interestingly, bone needles appear frequently in these Late Pleistocene sites. Yet in the following Holocene, when temperatures grew warmer, eyed bone needles become rare in the region. Despite numerous excavations, no eyed bone needle has been recovered from a Holocene-aged site in the northern Great Basin.

This pattern suggests that as climates warmed, the need for tightly sewn clothing may have diminished. Sewing, once critical, may have become less essential. The tools of survival shifted with the weather.

Clothing, in this sense, becomes a climate record. A needle is not just a needle. It is evidence of cold winds, frozen nights, and human determination to endure.

The Hidden Technologies of Early Life

The caves also yielded braided cordage and other fiber artifacts. These objects expand the story beyond hunting and stone tools. They speak of weaving, knotting, and crafting with plant fibers and animal hair.

Perishable technologies are often invisible in the archaeological record. They rot away, leaving only stone and bone behind. Yet these technologies may have been just as important, if not more so, in daily life.

Cordage can bind tools, create nets, secure shelters, and fasten clothing. Sewn hides can transform exposure into protection. Wooden trap components suggest strategic hunting practices beyond brute force.

Together, they form a picture of people who were not simply chasing prey across a frozen landscape. They were engineers of fiber and hide. They were problem-solvers responding creatively to environmental upheaval.

A Museum Collection Reawakened

Perhaps one of the most striking aspects of this discovery is where it began—not in a newly excavated trench, but in a museum collection.

The artifacts John Cowles gathered decades ago sat quietly for years. Only now, with refined techniques and renewed curiosity, are they revealing their secrets. The researchers note that other museum collections may hold similar untapped insights.

Sometimes, the future of discovery lies not in distant field sites but in drawers and shelves already filled.

Why This Research Matters

This study reshapes how we understand early human adaptation. For years, the focus on big-game hunting overshadowed other survival strategies. The lack of preserved perishable artifacts created a skewed narrative.

The Cougar Mountain Cave and Paisley Caves offer a corrective. They show that humans responded to climatic stress not only with weapons but with textiles and sewing. They demonstrate that innovation can be quiet and domestic as well as dramatic and deadly.

The fragment of sewn elk hide is small, but its implications are large. It suggests that during the Younger Dryas, people engineered tight-fitting garments to survive extreme cold. It connects climate change to technological response in a tangible way.

In a broader sense, the research highlights human adaptability. Faced with sudden cooling, people did not simply endure. They adjusted. They crafted. They stitched warmth into their lives.

And it reminds us that museum collections are living archives. With careful study and modern techniques like radiocarbon dating and ZooMS, objects once considered ordinary can transform our understanding of the past.

Twelve thousand years ago, someone sat with hide, fiber, and needle in hand. They pulled a cord through dehaired elk skin and tied a knot to secure it. That small act of sewing may have kept cold air at bay. Today, it stitches together a richer, more nuanced story of human resilience.

In the end, this research matters because it restores balance to our picture of the past. It shows that survival was not only about hunting the largest animals but also about mastering the smallest details—about closing seams, tying knots, and adapting with ingenuity when the world turned cold.

Study Details

Richard L. Rosencrance et al, Complex perishable technologies from the North American Great Basin reveal specialized Late Pleistocene adaptations, Science Advances (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aec2916