For nearly 40 years, Daniel Portnoy has been chasing a microscopic fugitive.

The culprit is Listeria monocytogenes, a foodborne bacterium infamous for causing listeriosis, a disease that can begin with fever and gastrointestinal illness but sometimes spirals into deadly sepsis or meningitis. Portnoy built his scientific life around understanding how this bacterium slips past our defenses, manipulates our cells, and survives inside us.

What he and his colleagues have now uncovered feels almost poetic. The same bacterium that once hid from the immune system may soon be used to awaken it. What once caused disease could become a powerful immune booster—and possibly a new weapon against cancer.

The Great Escape Inside Our Cells

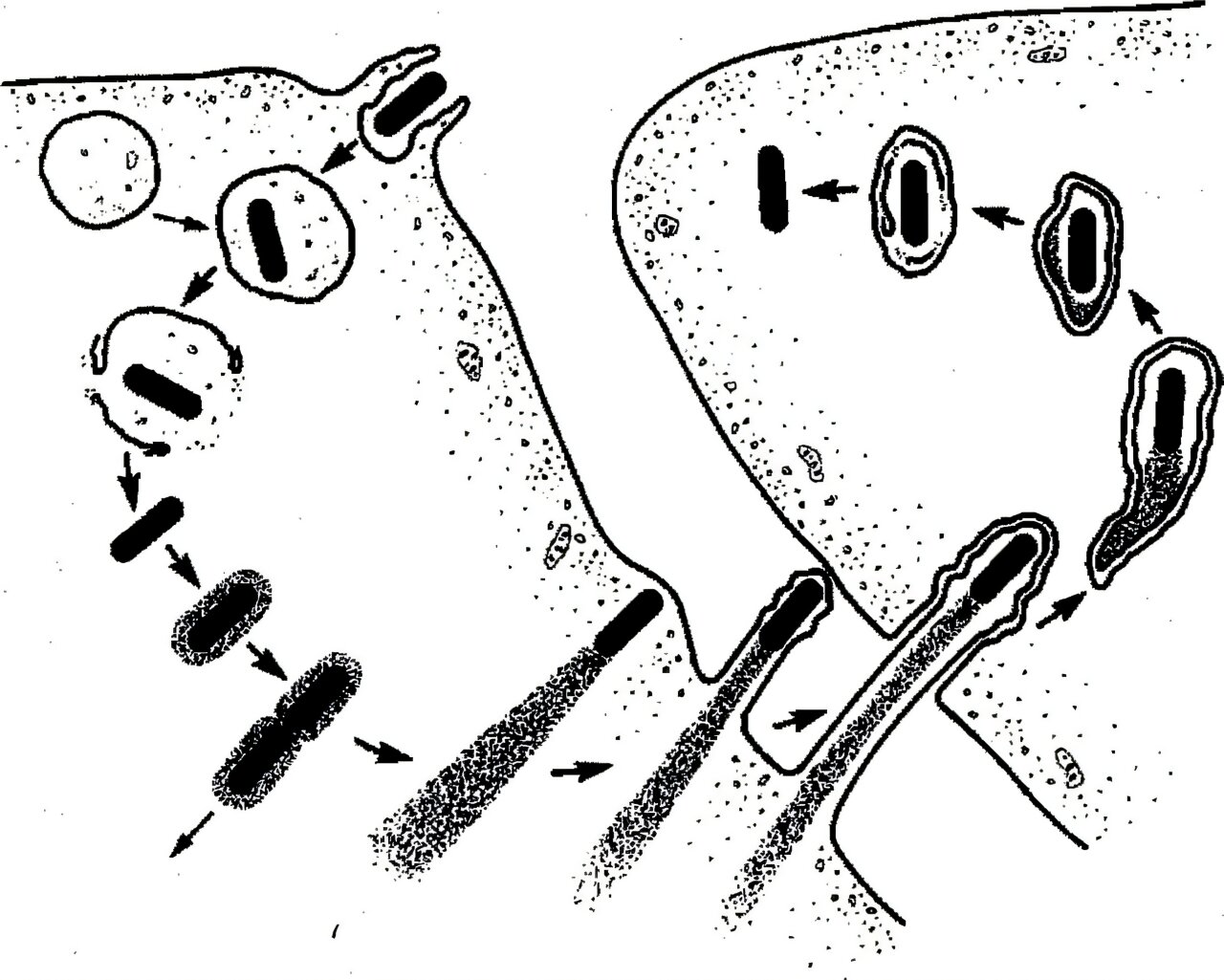

Decades ago, researchers believed that once Listeria was swallowed by immune cells called phagocytes, it would be trapped in a cellular compartment known as a phagosome, where invading microbes are digested and destroyed.

But Portnoy revealed a startling truth. Before digestion could occur, Listeria escaped.

Instead of being destroyed, the bacterium slipped out of the phagosome and into the interior of the cell. There, inside the cytoplasm, it set up shop, quietly reproducing and spreading from cell to cell. It even hijacked actin, a structural protein in the host cell’s skeleton, using it to push itself forward in finger-like protrusions that neighboring cells absorbed. This allowed the bacterium to spread without exposing itself to the immune system outside.

Listeria wasn’t just surviving. It was outmaneuvering its host.

Yet even while hiding, it triggered something remarkable. It activated the body’s adaptive immune system, prompting the production of cytotoxic T cells, also known as CD8 T cells, which could recognize and kill infected cells.

That spark would later inspire an entirely new idea.

Turning a Pathogen Into a Tool

In the early 2000s, Portnoy collaborated with a company called Aduro Biotech to transform Listeria into a cancer therapy. The strategy was bold. Engineers modified the bacterium to express cancer-specific antigens, hoping it would train the adaptive immune system to attack tumors.

But first, the bacterium had to be disarmed.

Portnoy deleted two genes required for Listeria to exit infected cells and spread. Without the ability to hijack actin and move into neighboring cells, the modified strain could still enter cells and stimulate immunity—but it became a thousandfold less virulent.

This strain was named LADD, short for Listeria attenuated double deleted.

Nearly 1,000 patients with pancreatic cancer and mesothelioma received this engineered bacterium in clinical trials. In mice, the results had been promising. In humans, however, the therapy didn’t generate the strong cytotoxic T cell response researchers had hoped for. Eventually, the trials were halted.

It could have ended there.

But science rarely moves in straight lines.

An Unexpected Clue

During the human trials, something curious emerged. While LADD did not strongly boost CD8 T cells in patients, it consistently activated another kind of immune cell: gamma delta T cells.

Unlike the adaptive immune system, which learns to recognize specific threats, the innate immune system responds more broadly and rapidly. Gamma delta T cells belong to this innate side. They are general-purpose killers, capable of attacking cancer cells or cells infected by pathogens—whether bacteria, viruses, or fungi.

In the years since the Aduro trials, evidence grew that gamma delta T cells can directly kill cancer cells and release signaling molecules that stimulate other immune warriors like macrophages and natural killer cells.

That observation changed everything.

Instead of trying to use Listeria to direct the adaptive immune system toward a specific tumor, what if it could be used to awaken the innate immune system more broadly?

That question led to the founding of Laguna Biotherapeutics, a startup cofounded by Portnoy three years ago.

Designing a Safer Bacterium

The team at Laguna Bio built on LADD’s foundation but made it even safer.

They deleted two additional genes, creating a quadruple-attenuated strain named QUAIL, short for quadruple attenuated intracellular Listeria. These deleted genes encode enzymes required to produce FMN and FAD, essential nutrient cofactors derived from riboflavin, or vitamin B2.

Inside cells, FMN and FAD are readily available. Outside cells, they are not.

By removing the bacterium’s ability to make these cofactors, the researchers created a strain that can grow only inside cells. It cannot grow in blood. It cannot grow in the intestine. It cannot grow in the gallbladder. These extracellular environments simply don’t provide what it needs.

In effect, Listeria has been transformed from a pathogen capable of spreading throughout the body into one confined to the intracellular world.

In mouse studies published in mBio, QUAIL proved as potent as LADD in stimulating immunity, while demonstrating enhanced safety. Because it cannot grow outside cells, it also cannot colonize medical devices like ports or implants often used by cancer patients.

The bacterium that once escaped immune capture is now carefully contained.

Awakening a Sleeping Immune System

Modern cancer immunotherapies typically target the adaptive immune system. Drugs such as checkpoint inhibitors attempt to reawaken suppressed immune cells within tumors.

But tumors are notoriously suppressive environments. They dampen immune responses, making it difficult for the body to fight back.

Listeria offers a different approach. The bacterium itself is seen as foreign, triggering a strong innate immune response. This response can overcome the suppression within tumors, potentially giving the immune system the push it needs.

Laguna Bio plans to test QUAIL in children with leukemia who have undergone unmatched bone marrow transplants. These patients face unique challenges. Their adaptive immune systems are deliberately suppressed to prevent transplant rejection, leaving them vulnerable to infection and cancer recurrence.

By stimulating gamma delta T cells, QUAIL could help these children fight infections, reduce graft-versus-host disease, and directly target remaining leukemic cells.

The therapy does not rely on teaching the immune system to recognize one specific cancer antigen. Instead, it amplifies a broad, innate response against any cell sending distress signals.

In earlier work posted on bioRxiv, researchers also reported that Listeria can be engineered to stimulate mucosal-associated invariant T cells, or MAIT cells, another innate immune population involved in defense against infections and possibly cancer.

The vision is expansive. Reinvigorate the immune system first. Then, if needed, guide it toward specific targets.

A Broader Horizon

If QUAIL proves safe and effective in pediatric leukemia trials at Stanford University Medical Center, its potential reach could extend further. Diseases such as multiple myeloma, lymphomas, neuroblastoma, sarcomas, and various solid tumors have shown responsiveness to increased gamma delta T cell activity.

The concept may even stretch beyond cancer. The team envisions possible prophylactic use against diseases like malaria, tuberculosis, and latent viral infections caused by intracellular pathogens.

At its heart, this strategy is about orchestration. As Laguna Bio CEO Jonathan Kotula explains, generating a comprehensive immune response requires carefully engaging the entire immune system. Attenuated Listeria appears uniquely capable of doing that.

Why This Research Matters

For decades, Listeria symbolized danger—a stealthy invader capable of slipping past our defenses. Now, through careful genetic engineering, it may become an ally.

The transformation of Listeria monocytogenes into QUAIL represents more than a clever tweak to a bacterium. It reflects a deeper shift in how scientists think about immunity. Instead of targeting cancer with ever more specific weapons, this approach seeks to awaken the body’s own broad defenses, particularly the often-overlooked innate immune system.

The research matters because it opens a new lane in cancer therapy. It suggests that boosting gamma delta T cells could help patients whose adaptive immune systems are weakened or suppressed. It offers a strategy informed not just by animal models but by human trial data. And it demonstrates how decades of basic research—painstakingly uncovering how a pathogen survives—can unexpectedly yield a therapeutic breakthrough.

A bacterium once feared for its ability to escape immune destruction may soon be used to help the immune system reclaim its power. In that reversal lies the quiet brilliance of science: understanding an enemy so deeply that you can turn it into a partner in healing.

Study Details

Victoria Chevée et al, Reprogramming Listeria monocytogenes flavin metabolism to improve its therapeutic safety profile and broaden innate T-cell activation, mBio (2026). DOI: 10.1128/mbio.03652-25

Rafael Rivera-Lugo et al, MAIT cells induced by engineered Listeria exhibit antibacterial and antitumor activity, bioRxiv (2025). DOI: 10.1101/2025.10.13.682223