Around 42,000 years ago, as early modern humans spread across Europe and the Near East, they faced the same challenge—how to survive and thrive in a world shared with Neanderthals, shaped by harsh climates, and defined by constant adaptation. Both groups carved stone into tools for hunting, building, and creating. Yet a new study reveals that while their tools may look alike, the minds behind them followed very different paths.

An international team of researchers has now shown that early Homo sapiens in these two regions independently developed their own distinct toolmaking technologies. The discovery, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, not only reshapes our understanding of prehistoric innovation but also offers a more complex picture of how culture and creativity evolved in our species’ earliest days.

The Puzzle of Ancient Innovation

For decades, archaeologists believed that early modern humans migrating from the Near East into Europe brought with them new technologies and cultural practices. The Near East—stretching from modern-day Lebanon through Israel and beyond—was long seen as a key crossroads of human dispersal out of Africa. According to this theory, much of Europe’s Paleolithic innovation originated there.

Yet, Dr. Armando Falcucci from the University of Tübingen and Professor Steven Kuhn from the University of Arizona saw a gap in that narrative. They wondered: Were these technological leaps truly imported by migrating populations, or could European groups have developed their own methods independently?

Their comparative study set out to test this question with scientific precision. The result was a fascinating revelation—that the similarities between Near Eastern and European stone tools masked deep, fundamental differences in how they were made.

Tracing the Tools of Two Worlds

The researchers focused on two major archaeological cultures: the Ahmarian culture of the Near East and the Protoaurignacian culture of southern Europe. Both emerged around 42,000 years ago, roughly when modern humans began replacing Neanderthals in Europe. For years, archaeologists assumed that the Protoaurignacian was simply a western branch of the Ahmarian—evidence of a technological tradition carried westward by migrating humans.

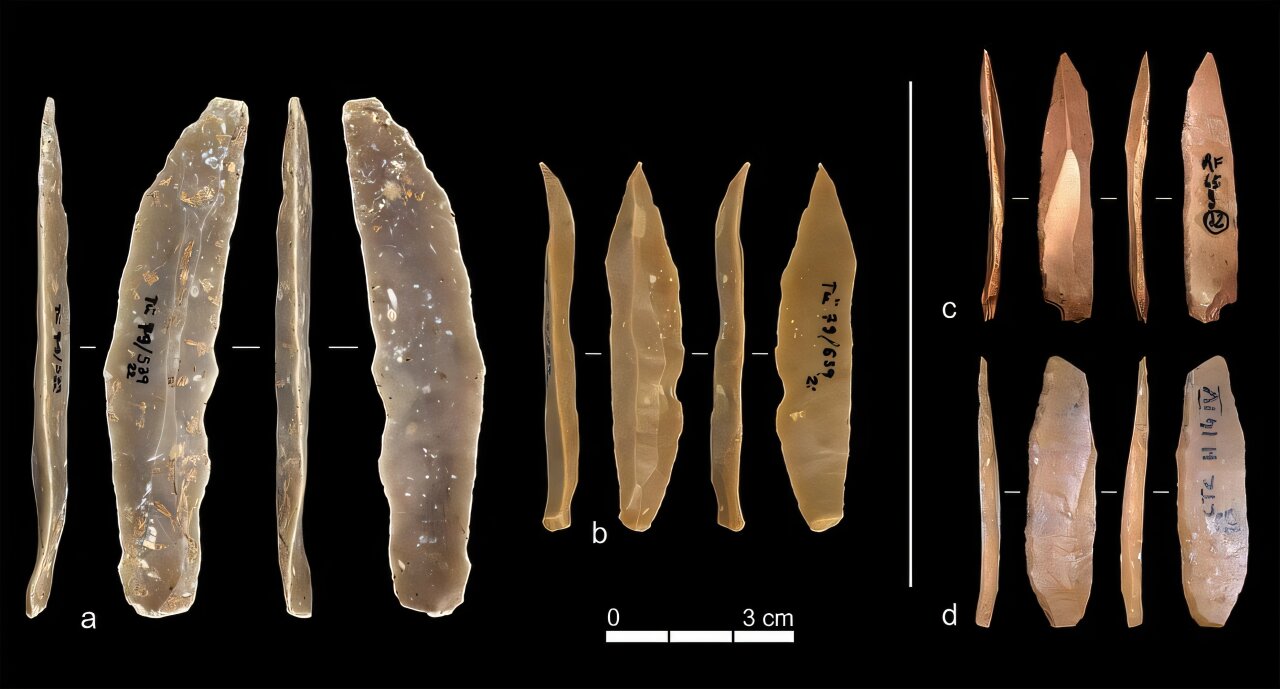

To test this, Falcucci and Kuhn conducted the first-ever quantitative analysis comparing artifacts from these two traditions. They studied thousands of stone tools—each one a frozen moment of prehistoric craftsmanship.

The Ahmarian samples came from Ksar Akil, a famous site near Beirut, Lebanon, which preserves one of the richest records of early modern humans in the Near East. For the Protoaurignacian, they analyzed artifacts from Grotta di Fumane near Verona, Riparo Bombrini near Ventimiglia, and Grotta di Castelcivita near Salerno—three key sites in Italy that document the earliest European innovations.

Looking Beneath the Surface

At first glance, the stone blades from both regions appeared similar. They were small, sharp, and standardized—ideal for fitting into wooden or bone handles to form composite tools such as spears and knives. But as Kuhn explained, appearances can deceive.

“Superficially, the stone tools from these different areas may look similar. But we wanted to look deeper, examining in detail how they were produced,” he said.

By meticulously reconstructing how ancient toolmakers shaped chert nodules—the flint-like stone commonly used—they discovered profound differences. The Ahmarian and Protoaurignacian craftspeople each followed unique production sequences, or “reduction strategies,” to create their blades.

Both cultures gradually moved toward smaller, more refined tools, reflecting the growing sophistication of early humans. Yet the methods they used to achieve this evolution diverged sharply.

Falcucci explained, “When comparing the sites, we focused mainly on the production of stone insets for composite tools, carefully reconstructing how chert nodules were shaped to strike off regular blades with sharp edges.”

Their analysis showed that Ahmarian toolmakers in the Near East and Protoaurignacian toolmakers in Europe developed their own technological traditions—each rooted in local innovations rather than imported ideas.

A Break from the Migration Hypothesis

This finding challenges a long-held assumption in Paleolithic archaeology: that every major technological leap in prehistoric Europe came from migration waves out of the Near East.

“Overall, the techniques of the Ahmarian and post-Ahmarian cultures in the Near East do not match those of the Protoaurignacian culture in Italy,” Falcucci concluded. “The differences in flaking methods suggest that European hunter-gatherers developed their projectile technologies independently.”

Professor Kuhn emphasized the significance of this realization. “The common assumption that all Paleolithic technological innovations in Europe were introduced through successive waves of migration from the Near East needs to be re-evaluated,” he said.

This study paints a more intricate portrait of human expansion—not as a single, continuous wave of progress flowing outward from one source, but as a network of creative communities innovating on their own, sometimes in parallel, sometimes in contact, and often with remarkable ingenuity.

A Complex Journey Across Continents

Falcucci and Kuhn’s work aligns with emerging genetic and fossil evidence showing that Homo sapiens began spreading across Eurasia at least 60,000 years ago. These early populations encountered, coexisted with, and even interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans—our now-extinct relatives.

As they adapted to different environments, from the Mediterranean coastlines to the cold steppes of Europe, these groups developed unique cultural identities and technologies. Rather than being mere recipients of innovation, they were creators in their own right.

“Our study adds to a growing body of research portraying modern human expansion into Eurasia as a complex, non-linear process,” Falcucci explained. “It underscores the importance of recognizing the often-underestimated scope of cultural interactions with our extinct relatives when reconstructing our species’ deep past.”

The Tools That Tell Human Stories

Every chipped stone carries a story—of thought, skill, and adaptation. To create a tool from raw rock required patience and precision, an understanding of how each fracture would travel through the stone. The blade fragments that archaeologists unearth today are not just ancient debris; they are expressions of the first human creativity, reflections of minds that could plan, experiment, and innovate.

By studying these objects, researchers like Falcucci and Kuhn are piecing together a narrative that is far richer and more diverse than previously imagined. Instead of a single “march of progress,” human history emerges as a mosaic of independent experiments in survival and expression.

The European and Near Eastern toolmakers of 42,000 years ago may never have met, but their shared drive to innovate speaks to something deeply human—the desire to solve problems, to improve, and to create.

Redefining the Origins of Culture

This research also has broader implications for how we understand culture itself. Innovation, the study suggests, does not need to be transmitted through migration or imitation; it can arise spontaneously in multiple places when humans face similar challenges.

As Professor Karla Pollmann, President of the University of Tübingen, noted, “Piece by piece, researchers are forming a clearer picture of the history of our ancestors and their cultural development, adding details or reporting surprising twists and turns. I am delighted that the University of Tübingen is also able to contribute to this process with new findings.”

The discovery reminds us that our species’ creativity is not limited by geography. Whether in the hills of Lebanon or the caves of Italy, ancient humans found their own paths toward progress—evidence that innovation was woven into the very fabric of who we are.

Rewriting the Human Story

Each new archaeological discovery refines our understanding of what it means to be human. Falcucci and Kuhn’s work challenges the simplicity of old models and replaces them with a vision of humanity as adaptable, inventive, and diverse.

The idea that early Europeans were not merely recipients of imported knowledge but pioneers in their own right reshapes how we see the origins of culture and technology. It suggests that the spark of creativity—the ability to imagine something new and make it real—has always been one of our defining traits.

In the end, these ancient stone blades are more than artifacts. They are voices from the deep past, whispering stories of intelligence and independence. They remind us that humanity’s journey was not a straight line but a web of discoveries, woven by countless hands across continents and millennia.

The tools may have been shaped by stone, but the minds that made them shaped the future.

More information: Armando Falcucci and Steven L. Kuhn, Ex Oriente Lux? A quantitative comparison between northern Ahmarian and Protoaurignacian, Journal of Human Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2025.103744. www.sciencedirect.com/science/ … 0047248425000971?via%3Dihub