High in the jungles of Mesoamerica, beneath the canopies where howler monkeys echo like spirits and the ruins of once-great cities crumble into vine-bound silence, the ancient Maya once etched stories not only into stone but also into human skin. These markings—bold, cryptic, and enduring—were not merely decorations. They were the imprints of identity, faith, hierarchy, and even punishment. But until recently, they remained as elusive as a whisper in a tomb. The deep past had given us glimpses—murals, ceramics, and conquistador chronicles—but no physical tools, no skin, no ink.

Now, for the first time in history, researchers believe they have uncovered the earliest known tattooing implements used by the ancient Maya. Hidden in the belly of a cave in Belize and forgotten for centuries, these tools are peeling back the layers of speculation and myth, offering a direct connection to the ancient artists of flesh.

A Painted People

The Maya were artists in every sense of the word. Their codices brimmed with intricate glyphs. Their temples rose like mountainous manuscripts etched with stelae, friezes, and murals. Their cities, from the towering pyramids of Tikal to the ceremonial avenues of Copán, whispered secrets of calendars, gods, and kings.

Body modification was part of this aesthetic and spiritual language. From cranial shaping and dental inlays to nose and ear piercings, the Maya body was a canvas—modified, adorned, and shaped according to social, religious, and cosmological ideals.

Tattoos were one of the most striking and symbolically potent forms of this self-transformation.

Ethnographic and colonial records—most notably from the Spanish friar Diego de Landa—reveal that the Maya painted themselves with elaborate motifs. Landa wrote that tattoos were created by cutting the skin and rubbing in pigments, a painful process performed after puberty and as part of religious rites. However, the friars, steeped in Christian doctrine, saw such practices through the lens of sin and suffering. What they considered savage was, in truth, sacred.

Artistic depictions from the Classic period (circa 250–900 CE) show individuals—often deities, rulers, or warriors—with what appear to be intricate, dark patterns on their skin. But were these tattoos or body paint? The distinction is crucial. Paint fades; tattoos endure. Paint adorns for celebration; tattoos enshrine memory, oath, and transformation.

The Linguistic Labyrinth of Ink

One major challenge in confirming ancient Maya tattooing practices lies in language. The Classic Mayan word tz’ihb means both “to write” and “to paint.” It referred to any application of lines or designs, whether on bark paper, stone, or skin. This semantic ambiguity clouds interpretations. When scribes wrote of “painting the body,” were they describing ceremonial pigments… or the slow, piercing inscription of a tattoo?

In murals from sites such as Bonampak, warriors and dancers appear with bold black markings curling along their arms, faces, and torsos. The shapes—spirals, dots, loops, animal forms—seem more permanent than festive. But paint can mimic permanence. Without physical remains or instruments, archaeologists lacked the evidence to say definitively: these were tattoos.

Until now.

The Cave of the Silent Artists

In the late 1990s, deep within the Actun Uayazaba Kab cave in west-central Belize—a site whose name roughly translates as “Cave of the Shrouded Hand”—a team of archaeologists from the Western Belize Regional Cave Project uncovered an assemblage of artifacts.

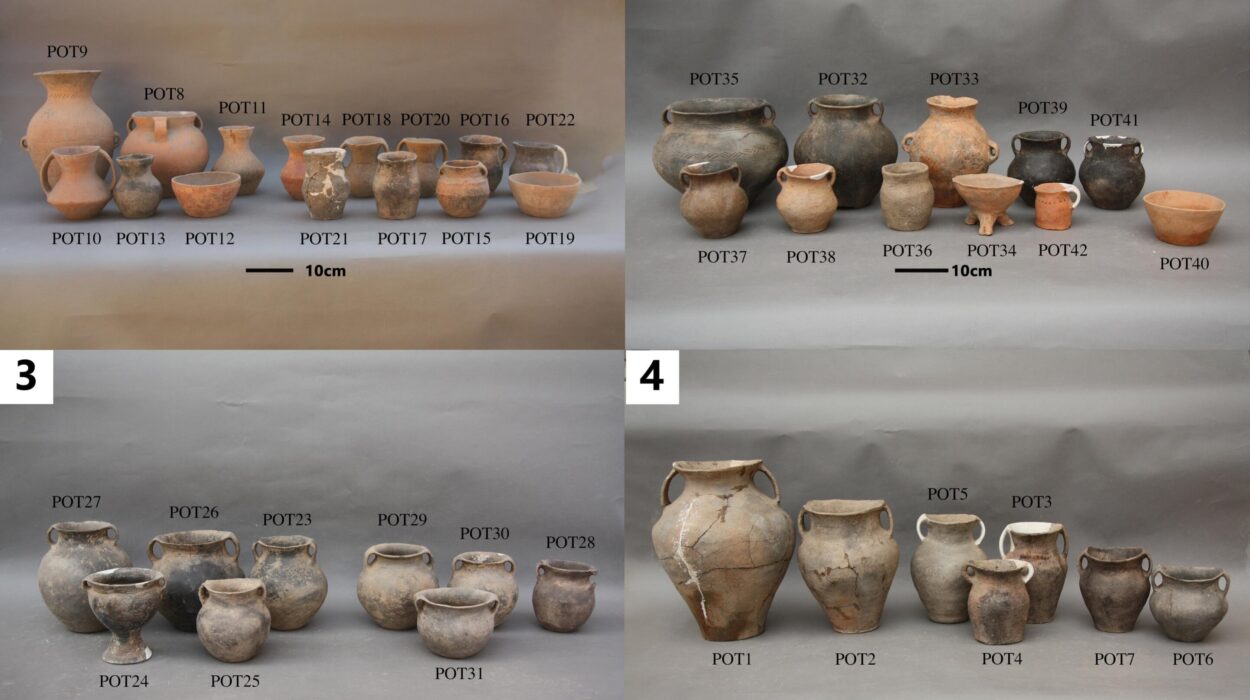

Among pottery shards, shell pendants, jade beads, and a pristine obsidian blade were two innocuous-looking stone tools—burins, finely tipped and shaped to a needle-like precision. For decades, these tools sat in storage, catalogued but unexamined for specific use.

In 2024, Dr. W. James Stemp and his team decided to reexamine them. With advances in microscopic use-wear analysis and experimental archaeology, they revisited the burins with a new hypothesis: could these be tattooing implements?

The results, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, were groundbreaking.

A Tool Reborn in Flesh

To test their hypothesis, the researchers analyzed the microscopic wear patterns at the tips of the burins. These patterns did not match those associated with common uses like drilling shell or bone, nor with bloodletting—another sacred practice often performed with obsidian blades or stingray spines.

Instead, the wear was remarkably similar to the abrasions and polish found on modern experimental tattoo tools.

The team then created a replica burin and used it to tattoo fresh pig skin—a common analogue for human dermis due to its similar structure. The results were astonishing. The replica produced nearly identical use-wear traces, and the motion of puncturing pigment into flesh with a fine stone tip echoed the probable action of the ancient tool.

Furthermore, residue analysis revealed traces of a black substance—possibly ink—still clinging to the tip of the original burin, preserved by the unique microclimate of the cave.

Symbols of Valor, Suffering, and Spirit

Why would such tools be found in a cave, alongside ceremonial items and human remains? The answer lies in the Maya’s understanding of the cosmos and sacred space.

Caves, to the Maya, were not just geological features. They were portals—entrances to Xibalba, the underworld, and homes of gods, spirits, and ancestors. Important rituals were often conducted in such liminal spaces. They were where the world of the living and the divine touched.

Dr. Stemp suggests that these tools were not discarded casually but deposited intentionally, likely after a single use. “As a ritualized or ceremonial practice, we suspect the use-life of a stone tool used for tattooing was connected to a particular tattooing event involving a specific person,” he explains.

In Maya cosmology, objects could become imbued with k’uh—spiritual essence or life-force—during ritual use. Just as a sacred vessel might be “killed” (deliberately broken) after fulfilling its function, tattoo tools, once spiritually activated, may have been “retired” to sacred locations such as caves.

The Faces Behind the Marks

What did these tattoos look like? Based on both iconographic and ethnographic evidence, two primary styles emerge: animal motifs and geometric patterns.

Animal tattoos often depicted powerful creatures—jaguars, bats, eagles, serpents—each associated with specific gods, traits, or roles. A bat might symbolize the underworld and night. A serpent could evoke rebirth and divine vision. Warriors may have borne jaguar spots or eagle wings as emblems of prowess.

Geometric tattoos featured loops, spirals, curves, and dots. These symbols may have conveyed lineage, cosmic beliefs, or achievements.

Placement of tattoos varied. Men are believed to have been tattooed on the arms, legs, chest, and face. Women often bore tattoos on the thighs, breasts, and backs. These distinctions weren’t merely aesthetic—they communicated gender, status, and purpose.

But not all tattoos were marks of pride. Some were punitive.

Spanish records and indigenous oral traditions suggest that tattoos could serve as punishment for criminals or those who violated religious taboos. Like brands, these tattoos rendered transgressions permanent and public.

The Puncture of Passage

Tattooing among the Maya was not a casual act. It marked transitions—adolescence, marriage, warrior initiation, religious ordination. Each puncture was a rite, each drop of blood a sacrifice.

Pain was integral. Unlike modern electric machines, Maya tattooing required repeated puncturing with sharpened tools—possibly obsidian, bone, or stone—while pigment was rubbed into the wounds. The process was not only excruciating but spiritually purifying. Pain forged the connection between the physical and supernatural realms.

Participants often fasted or ingested hallucinogens prior to being tattooed, entering altered states that allowed communion with deities or ancestors. In this trance-like state, the tattoo was not just received; it was dreamed.

Tattooers of the Sacred

Who performed these ceremonies? Likely, the tattooers were specialists—shamans, artists, or priests—who understood the symbolic language of the designs and the spiritual protocols of the ritual.

These individuals may have prepared their own inks from charcoal, tree resins, minerals, and plant-based dyes. The exact recipes are lost to time, but residue on ancient implements may soon reveal their alchemical secrets.

To wield the needle was to command respect. A tattooer wasn’t just a craftsman; they were a spiritual mediator, an agent of transformation. The tool was their sacred instrument, and the body their scripture.

The Archaeological Ink is Still Wet

The discovery of tattooing tools at Actun Uayazaba Kab is not the end of the story—it is the beginning of a new chapter in Maya archaeology. It challenges assumptions about the visibility of intangible practices and opens fresh avenues of inquiry.

Could other tools previously categorized as “drills” or “engravers” be tattoo implements? Could residue analysis on ceramics or burials reveal more about the prevalence and style of tattooing?

Future excavations and laboratory analyses may uncover even older tools, inks, or—by some miracle of preservation—tattooed human remains. (While rare, such discoveries have occurred in other regions, such as with Ötzi the Iceman in Europe or the Scythian mummies in Siberia.)

The Skin of the Ancestors Lives On

For too long, the skin of the ancient Maya has remained invisible—erased by time, climate, and conquest. But through these tools, we begin to glimpse it again. Not as pale bone or mute artifact, but as a living surface, rich with meaning and artistry.

Maya tattoos were maps of identity. They told who you were, where you stood, what gods you honored, and what pains you bore. They were mnemonic, ceremonial, spiritual.

Today, modern Maya communities are reclaiming tattooing traditions, blending ancient motifs with contemporary designs. The ink flows again—across arms, backs, and hearts—not as a revival, but as a continuation.

As archaeologists, artists, and descendants trace these lines, they remind us: the past is not lost. It is written into us. Sometimes, all it takes is a sharp stone and a little ink to read it.

Reference: W.James Stemp et al, Two ancient Maya tattooing tools from Actun Uayazba Kab, Roaring Creek Valley, Belize, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105158