When we imagine the history of money, the story often unfolds like a neat timeline: first came barter, then coins, then paper bills, then modern credit and digital payments. It’s a tidy progression, easy to teach and easy to believe. But new research led by University at Albany anthropology professor Robert M. Rosenswig challenges this familiar tale. His work suggests that the roots of money are not in the marketplace but in government accounting systems, and that ancient tally sticks—simple notched pieces of wood or bone—hold the key to understanding money’s true origin.

According to Rosenswig, the orthodox economic view, which treats money primarily as a neutral medium of exchange, doesn’t fit the historical record. Instead, tally sticks show that money emerged as a political and institutional tool, deeply tied to taxation, debt, and state authority. This revelation matters not only for historians but also for how we think about government spending, debt, and fiscal responsibility today.

Rethinking What Money Really Is

The conventional story of money is intuitive: people bartered before money existed, but barter was inefficient because it required a “double coincidence of wants.” Money, then, supposedly emerged as a universal commodity—gold, silver, salt, shells—that smoothed trade and fueled the growth of markets. This explanation, still taught to students around the world, presents money as an invention of markets and governments as latecomers who interfere with their natural efficiency.

But Rosenswig points out that anthropologists have long known this version doesn’t match reality. Barter was never the foundation of entire economies. Instead, it showed up only at the margins—between strangers, during times of currency shortage, or in isolated transactions. Human societies before coinage had complex systems of obligations, gifts, and accounting that organized exchange without relying on barter as the norm.

Tally sticks, he argues, flip the conventional story on its head. They reveal that money began as a way for governments to mobilize resources, enforce obligations, and keep track of debts. Rather than being a scarce commodity, money was—and remains—an accounting system backed by political authority.

Ancient Tally Sticks Across Civilizations

What makes tally sticks especially compelling is that they were independently invented in very different parts of the world—England, China, and the Maya world—without any cultural connection. And in each case, their primary use was not commercial exchange but the recording of obligations to rulers.

In medieval England, sheriffs used hazelwood sticks to document tax payments owed to the Exchequer. The sticks were split down the middle, each half holding identical notches that represented the obligation—one half kept by the taxpayer, the other by the crown. Over time, these “assignment tallies” began circulating like debt instruments, a kind of state-backed financial paper centuries before modern bonds. One remarkable surviving example is an 8-foot-long tally stick that records a £1.2 million loan to King William III, a debt that, technically, was never repaid.

In China, tally sticks made from bamboo appeared as early as the 3rd century BCE. Known as fu tallies, they were split in half by officials known as “knife-and-brush” clerks and used to track payments of grain, silk, or coins. Their durability and resistance to forgery made them an ideal tool for tribute collection. Centuries later, Marco Polo described their use during the Yuan dynasty, astonished by their long-standing role in state finance.

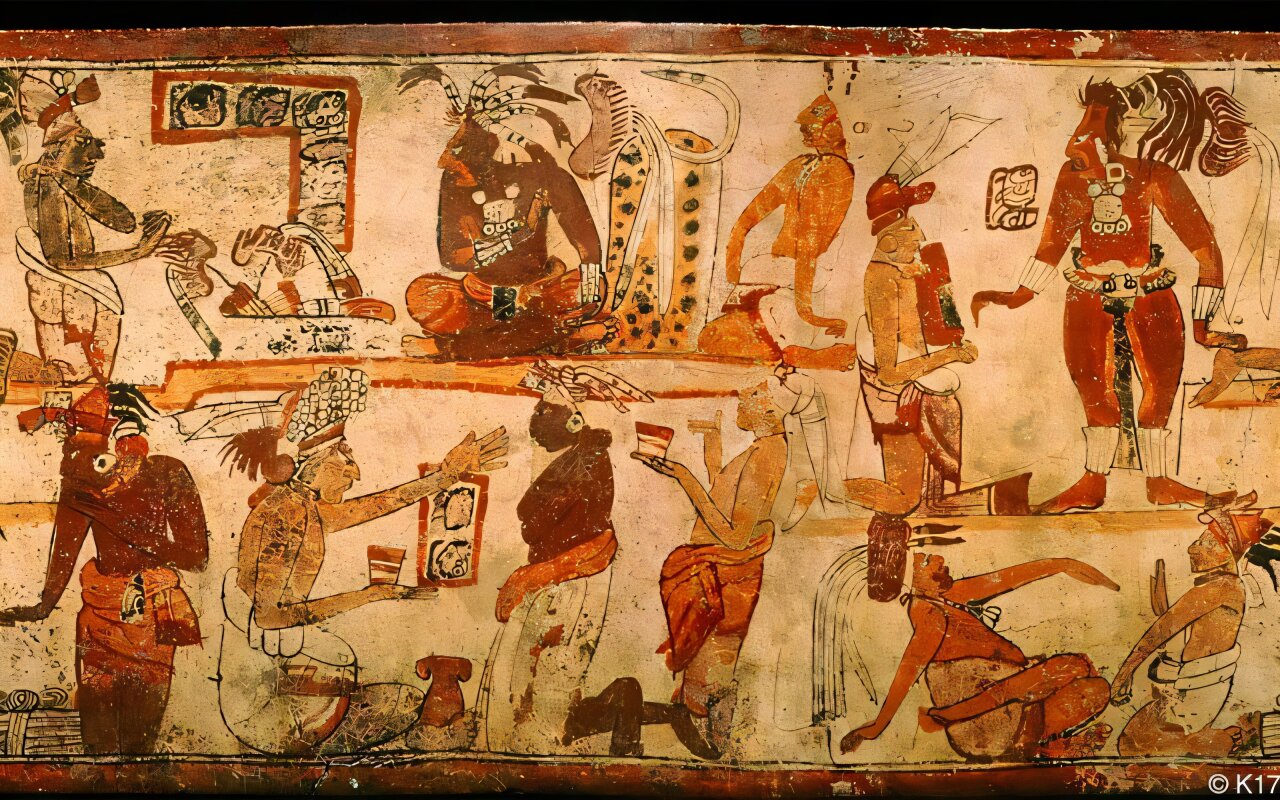

In the Maya world, bone tally sticks appear in the Late Classic period (600–900 CE). These artifacts, often painted with court scenes or royal burials, were bundled with tribute items like maize, textiles, or labor obligations. They served as symbolic tokens of debts owed to rulers rather than as instruments of market exchange.

Despite their differences, all three systems shared a common thread: tally sticks were state tools for recording obligations, not spontaneous inventions of barter-based trade.

What Tally Sticks Tell Us About Money

The lesson from tally sticks is clear: money’s origins lie not in markets but in states. They remind us that money is not a “thing” but a system of trust, record-keeping, and authority. It is a way for governments to organize resources, collect taxes, and mobilize societies.

This historical perspective challenges the orthodox economic belief that governments are financially constrained in the same way households are. If money began as an accounting system, then governments do not “find” money in the economy; they create it. They spend first, then tax later to manage inflation and redistribute resources. Seen this way, the analogy of government budgets as household checkbooks collapses.

Rosenswig argues that austerity policies, often justified on the basis of “balancing the books,” are historically and conceptually misguided. Instead, governments with fiscal sovereignty have far greater capacity to invest in public goods, support workers during downturns, and respond to crises than orthodox models suggest.

A Different Way to See Money

This rethinking of money’s history has profound implications for our present and future. If money is a political tool rather than a neutral commodity, then debates about public spending, debt, and taxation shift from questions of scarcity to questions of policy. The issue is not whether a government can spend, but how it chooses to spend—and for whose benefit.

Rosenswig’s study also highlights anthropology’s contribution to economic debates. By looking at real historical evidence across civilizations, anthropologists remind us that money is not timeless or universal. It has always taken different forms, from tally sticks to shells, from coins to digital balances, depending on political and social needs.

The tally stick is not just an artifact of the past—it is a mirror reflecting the true nature of money today. Far from being a natural outgrowth of barter, money has always been about power, obligation, and the ability of states to mobilize resources.

The Continuing Story of Money

The story of tally sticks may feel far removed from our modern world of contactless payments, cryptocurrencies, and global financial markets. Yet the parallels are striking. Just as medieval tally sticks circulated as debt instruments, modern government bonds serve as tools of fiscal policy. Just as Chinese bamboo tallies represented grain or silk owed to the state, today’s tax receipts and digital ledgers represent obligations enforced by law.

What unites them is not their physical form but their political foundation. Money is, at its heart, a system of trust enforced by institutions. Recognizing this truth may help societies move beyond simplistic metaphors of scarcity and toward more creative, humane approaches to public policy.

In Rosenswig’s words, “Studying the past reminds us that money is not timeless or universal in form. It is a political tool, and how we choose to use it today is a matter of policy, not natural law.”

By reassessing money’s origins through the lens of tally sticks, we are invited to see money not as a cold, impersonal force of markets, but as a deeply human invention—an evolving system that has always been about relationships, authority, and the shared responsibilities of community.

More information: Robert M. Rosenswig, Ancient Tally Sticks Explain the Nature of Modern Government Money, Journal of Economic Issues (2025). DOI: 10.1080/00213624.2025.2533734