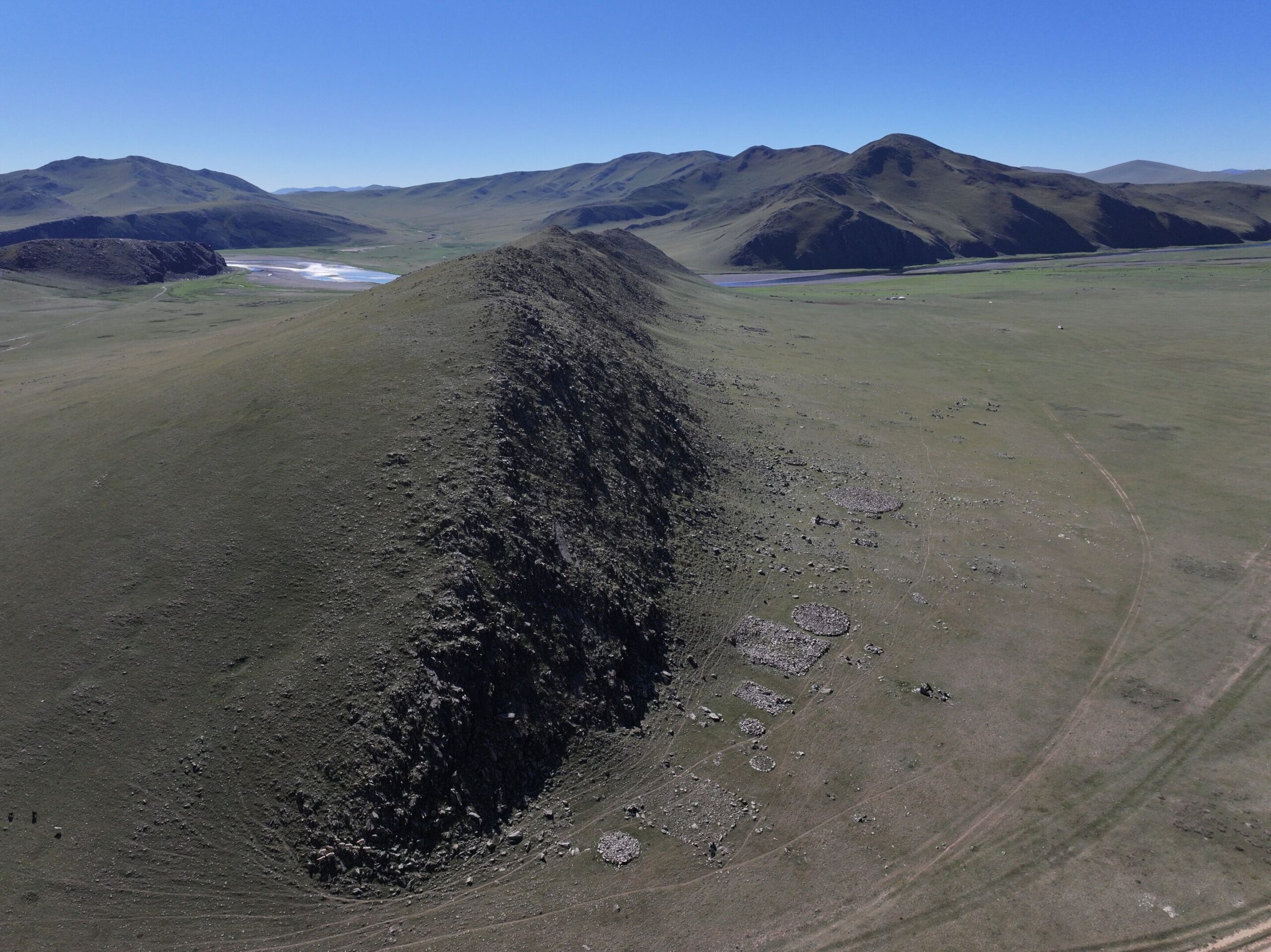

Across the windswept grasslands of Mongolia, the vast Eastern Eurasian Steppe stretches toward the horizon, a landscape that has long been a crossroads of human migration, innovation, and cultural exchange. For thousands of years, this environment shaped the lives of nomadic herders whose mobility and resilience allowed them to thrive where farming was impossible. Yet, beneath the rolling hills and rugged valleys lies another story—one written in stone graves and preserved in ancient DNA.

A new interdisciplinary study, combining archaeology and genetics, reveals that during the Late Bronze Age (approximately 1500 to 1000 BCE), two distinct nomadic groups lived side by side in central Mongolia for centuries. They shared mountains for their rituals, they buried their dead in the same valley, yet they remained separate—culturally and genetically. Their coexistence offers rare insight into how prehistoric communities interacted, and how cultural identity can endure even in the face of close contact.

Two Peoples, One Valley

The Orkhon Valley of central Mongolia, a place later famed as the heart of the Xiongnu Empire and the Mongol Empire, was already a site of deep cultural significance thousands of years earlier. Archaeological evidence shows that two nomadic groups converged here during the Bronze Age.

One group, whose roots stretched across western and central Mongolia, buried their dead in the tradition of the Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex (DSKC). Their graves featured large stone mounds, and the deceased were laid to rest facing northwest. The other group, living in the southern and eastern regions of the country, practiced a different ritual. They constructed smaller, figure-shaped stone graves, carefully arranging their dead to face southeast.

Both groups returned to the same sacred mountain slopes to bury their loved ones. To a modern observer, this mingling of burial grounds suggests cooperation, or at least tolerance. Yet the differences in grave design and body orientation reveal that these communities maintained strong cultural boundaries, even while sharing the same physical and spiritual landscape.

The Hidden Story in DNA

Archaeology alone could never fully explain this coexistence. That is why researchers turned to ancient DNA. By analyzing human genomes preserved in these burials, scientists uncovered a striking truth: the two groups remained genetically distinct for roughly 500 years.

This finding is remarkable. In most parts of prehistory, when different communities came into contact, intermarriage gradually blurred genetic lines. But here, in the heart of the Eurasian Steppe, cultural rules seem to have shaped marriage choices so strongly that genetic boundaries endured for centuries.

Dr. Ursula Brosseder of the Leibniz-Zentrum für Archäologie (LEIZA), one of the study’s lead authors, emphasizes the significance: “Globally, we have very few examples from prehistory where we can identify such patterns or the underlying social rules that shaped marriage practices. This shows that cultural identity was deeply embedded in everyday life.”

In other words, these communities were not just separated by burial rites; their very bloodlines were shaped by cultural choices about whom one could and could not marry.

The Rise of the Slab Grave Culture

Around 1000 BCE, everything changed. A new burial tradition spread across Mongolia—the Slab Grave culture. These graves, constructed with stone enclosures, first appeared in the east but quickly advanced westward, overtaking the traditions of the Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex.

This was not just a change in funerary style. Genetic analysis shows that the people buried in Slab Graves were overwhelmingly connected to the eastern population, with almost no genetic continuity from the earlier western groups. This suggests that the westward spread of Slab Grave traditions was carried not only by ideas but also by people.

Professor Jan Bemmann of the University of Bonn explains: “Our new data show that this shift was not only cultural but also genetic. The genetic profiles of individuals buried in Slab Graves show little connection to the previously dominant western groups. This suggests that a large wave of newcomers from the east entered the region, replacing the western population almost entirely.”

This replacement was so complete that even centuries later, during the powerful Xiongnu Empire (200 BCE–100 CE), the western genetic legacy had all but vanished. Despite the empire’s reputation for absorbing diverse groups, the DNA of the earlier western herders left no detectable trace in its population.

Deep Roots in the Steppe

The story of the western group did not begin in Mongolia. Genetic evidence reveals their ancestry was tied to the Afanasievo and Khemtseg cultures, pastoralist communities that had spread mobile herding practices across Central Asia more than 2,000 years earlier. In them, we glimpse the earliest wave of steppe pastoralism, which transformed vast regions by enabling people to follow herds, milk animals, and build societies not dependent on crops.

This Bronze Age legacy reminds us that the steppe was never static. It was a place of waves—of people, ideas, and practices—each shaping the next. The disappearance of one group’s genetic footprint did not mean the end of their influence. Instead, their cultural contributions lived on in the pastoral lifeways that defined the region for millennia.

Cultural Coexistence without Mixing

The study’s most striking conclusion is that cultural coexistence does not necessarily lead to genetic blending. Two populations can live side by side, sharing landscapes and perhaps even trading goods or exchanging knowledge, while still drawing firm boundaries around identity.

For the Bronze Age herders of Mongolia, these boundaries were expressed in burial traditions and in rules about marriage and kinship. By maintaining these lines for half a millennium, they preserved their distinctiveness even in the face of proximity.

As Dr. Brosseder notes, “This demonstrates that cultural coexistence does not necessarily lead to genetic mixing—a phenomenon with profound implications for how we interpret early human societies and their dynamics.”

The Significance of the Study

This research, published in Nature Communications, represents one of the most detailed attempts to integrate archaeology and genetics in the study of prehistoric Mongolia. It was the product of an international collaboration involving the University of Bonn, LEIZA, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Harvard University, Seoul National University, and the Institute of Archaeology of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences, among others.

Drawing on more than a decade of work under the Bioarchaeological Research on Cemeteries of the Upper Orkhon Valley (BARCOR) project, the team’s findings illuminate how culture and biology intersected in one of the world’s earliest centers of animal husbandry.

A Window into the Human Past

The Late Bronze Age steppe was a world of herders, horses, and horizons without end. For the people who lived there, cultural identity was as important as survival, shaping not just the way they buried their dead but also the very genetic legacy they passed on.

By bringing together stones, bones, and genomes, this study offers a rare glimpse into how two worlds coexisted in one land, and how the tides of history can preserve, transform, or erase entire populations.

In the silence of the Orkhon Valley, where mountains still guard ancient graves, the story of these herders endures—a reminder that human history is never simple, and that identity can be as enduring as stone and as fragile as memory.

More information: Juhyeon Lee et al, Slab Grave expansion disrupted long co-existence of distinct Bronze Age herders in central Mongolia, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63789-1