In 1977, during an excavation at the prehistoric site of Bòbila Madurell in Sant Quirze del Vallès, Barcelona, archaeologists uncovered a small but curious object. At first glance, it seemed unremarkable—a polished fragment of ivory just over ten centimeters long, delicately shaped and carrying faint traces of red pigment. For decades, it rested quietly in the Museu d’Història de Sabadell, waiting for a closer look.

Now, nearly half a century later, researchers from the Prehistoric Studies and Research Seminar (SERP) at the University of Barcelona have revealed its astonishing identity: the piece is made from the lower incisor of a hippopotamus. This identification makes it the oldest known artifact of hippopotamus ivory in the Iberian Peninsula, dating back to the second quarter of the third millennium BC—deep in the Copper Age.

This finding does more than add a curious item to museum shelves. It transforms how we think about prehistoric societies in Iberia and their far-reaching connections to distant lands.

Ivory from Afar: A Puzzle in Prehistoric Iberia

The Copper Age in the Iberian Peninsula was a time of growing complexity. Communities were beginning to establish stronger social hierarchies, experiment with metallurgy, and develop intricate cultural practices. Yet one fact makes this ivory piece particularly extraordinary: hippopotamuses were not native to the Mediterranean. There were no hippos wandering the Iberian rivers, no local sources of such ivory.

Its very presence in Catalonia suggests that it traveled hundreds, perhaps even thousands of kilometers, most likely from the eastern Mediterranean. The object is therefore not just a personal possession—it is evidence of long-distance exchange networks connecting Iberian communities to broader Mediterranean trade routes. Such connections remind us that even 4,500 years ago, people were not isolated. They were part of a world already crisscrossed by routes of exchange, where exotic materials carried symbolic weight as well as practical value.

The Science Behind the Discovery

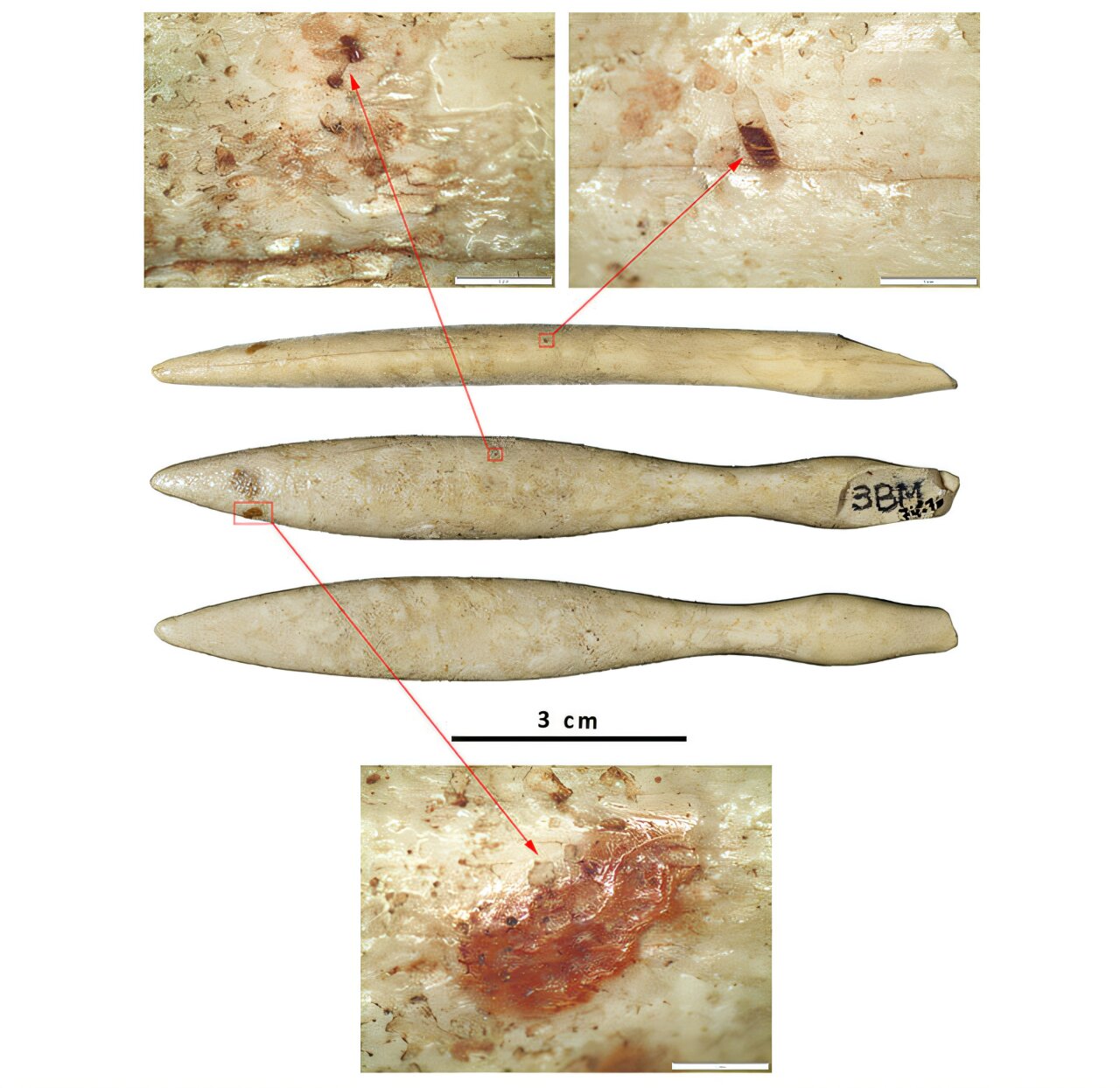

To identify the object’s true origins, researchers turned to modern analytical techniques. They employed Fourier transform infrared spectrometry (FTIR), a powerful method that detects the unique molecular signatures of materials. Combined with anatomical and taxonomic study, this analysis confirmed that the object was indeed crafted from the tooth of Hippopotamus amphibius.

The piece measures just over 10 centimeters in length, with a maximum width of 13.2 millimeters, and weighs 11 grams. Its polished surface suggests careful crafting, while small traces of red pigment hint at symbolic or decorative use. This pigment, made from iron oxyhydroxides mixed with an organic binder such as animal fat, gives the artifact an added layer of cultural meaning.

Radiocarbon dating of the archaeological context places the object firmly in the second quarter of the third millennium BC, a time when Iberian societies were undergoing major transformations in technology, rituals, and social organization.

What Was It Used For?

The mystery of the hippopotamus ivory does not end with its identification. Its original function remains a subject of debate. Researchers have proposed that it might be a stylized human figurine or idol, possibly linked to religious or symbolic practices. If so, the choice of exotic ivory would have made it an object of prestige, perhaps marking social status or spiritual significance.

But other possibilities remain. The piece could have served a practical purpose, perhaps as a tool in textile production. This idea is supported by the presence of spindle whorls—tools for spinning thread—found in the same structure. The polished surface and traces of pigment suggest it may have been used in a ritual context tied to textile work, which itself often carried symbolic weight in ancient societies.

The ambiguity of its purpose underscores the richness of archaeology. Sometimes, the most captivating discoveries are those that raise more questions than they answer.

Exotic Materials and Social Complexity

The significance of this find extends beyond the artifact itself. The hippopotamus ivory invites us to think about how exotic materials shaped the societies of the Copper Age. Access to rare resources like ivory was not just about utility—it was about identity, power, and connection. Possessing an object made from a material as exotic as hippopotamus ivory would have marked its owner or community as part of a wider network, participating in exchanges that stretched far beyond their local world.

We already know that African and Asian elephant ivory reached southern Iberia during the same period, likely through North African routes. Hippopotamus ivory, however, is far less common in the archaeological record and usually associated with later eras. Its appearance in Catalonia suggests that alternative trade routes—possibly linked to the north-western Mediterranean—were already active during the Chalcolithic.

Such routes may even echo older traditions of contact, like those associated with the Middle Neolithic Sepulcres de Fossa (pit graves) culture in Catalonia. The Bòbila Madurell object therefore not only expands the history of ivory use in Iberia but also opens new avenues for exploring prehistoric networks of contact and cultural exchange.

A Glimpse into a Distant World

When we look at the polished fragment of hippopotamus ivory, we are gazing across nearly five thousand years. We see the hand of an artisan who carefully shaped it, perhaps imbuing it with meaning through red pigment. We imagine the journeys it took—whether across seas or through hands of traders—before finding its way into a Copper Age community in Catalonia.

This single object encapsulates a broader truth about humanity: even in prehistoric times, people were not isolated villagers living in closed worlds. They were explorers, traders, artisans, and dreamers. They sought out rare materials, valued beauty and symbolism, and built connections across vast distances.

Conclusion: More Than an Artifact

The discovery of the hippopotamus ivory at Bòbila Madurell is not just about a small, polished object. It is about the web of relationships that stretched across the ancient Mediterranean, linking communities through materials, ideas, and symbols. It is about the emergence of social complexity in Iberia, where exotic imports began to carry prestige and meaning.

Most of all, it is about our enduring curiosity. Every artifact from the past is a message across time, and this one speaks of journeys, connections, and mysteries still waiting to be unraveled. The hippopotamus ivory of Catalonia reminds us that even the smallest objects can open vast horizons of understanding, bridging the gap between our world and that of our distant ancestors.

More information: José Miguel Morillo León et al, First evidence of hippopotamus ivory exchange networks in north-eastern Iberian Peninsula: The object of Bòbila Madurell (Barcelona, Spain), Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105375