The story of the polar bear has long been told as a tale of ice and endurance, a species shaped by cold oceans and drifting floes. But new research from the University of East Anglia suggests that the narrative may be shifting in real time. Rising temperatures are not only reshaping the landscape in which these bears live; they appear to be rewriting the animals’ DNA itself. In southeastern Greenland, where the Arctic grows warmer and sea ice grows scarce, polar bears may be responding at the molecular level in ways no one expected. Their survival, it seems, may depend on tiny genetic elements that leap through the genome like sparks in a fire.

Where the Landscape Splits the Species

In the remote expanse of Greenland, two populations of polar bears live under dramatically different skies. To the northeast, temperatures remain colder and stable, preserving the sea ice that traditionally anchors polar bear life. Far to the southeast, the picture is starkly different. Here the environment is warmer, less predictable, and increasingly ice-free. The challenges mount with each degree of warming: isolation, disappearing hunting grounds, scarcity of seals. It is also a glimpse of what scientists believe much of the Arctic will become in the future.

Scientists at UEA turned to these contrasting habitats to ask a pressing question: could the bears’ genetic machinery be changing in response to their shifting worlds? Their study, published in the journal Mobile DNA, compares blood samples from northeastern and southeastern bears, focusing on the activity of what researchers call “jumping genes”—small, mobile pieces of DNA capable of altering how other genes behave. These genomic wanderers have long been part of the evolutionary toolkit, but their role in real-time adaptation has remained largely elusive.

The DNA That Would Not Sit Still

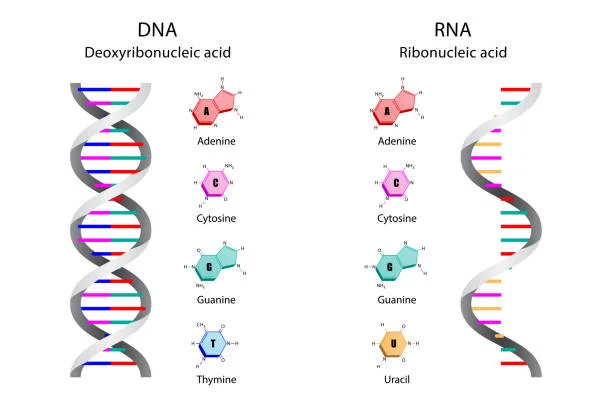

Lead researcher Dr. Alice Godden explains the stakes in simple terms. “DNA is the instruction book inside every cell, guiding how an organism grows and develops,” she said. By examining RNA expression—the molecular signals that reveal which genes are active—the team could watch this instruction book being read and modified under different environmental pressures.

The result was striking. “By comparing these bears’ active genes to local climate data, we found that rising temperatures appear to be driving a dramatic increase in the activity of jumping genes within the southeastern Greenland bears’ DNA,” Dr. Godden said. These bears, living in the warmest corner of Greenland, were experiencing far more genetic reshuffling than their northern relatives.

“Essentially,” she added, “this means that different groups of bears are having different sections of their DNA changed at different rates, and this activity seems linked to their specific environment and climate.”

For the first time, researchers had evidence that a wild mammal species may be undergoing measurable DNA changes directly tied to warming temperatures. Dr. Godden described it plainly: “This finding is important because it shows, for the first time, that a unique group of polar bears in the warmest part of Greenland are using ‘jumping genes’ to rapidly rewrite their own DNA, which might be a desperate survival mechanism against melting sea ice.”

A Narrow Opening for Survival

The southeastern bears are living in a habitat already resembling conditions predicted for many Arctic regions later this century. With sea ice disappearing, their traditional seal-based diet becomes harder to obtain. The study found changes in gene expression linked to fat processing, suggesting that these bears may be slowly adjusting to the rougher, plant-based foods available in warmer areas. It is an adaptation born not of preference but necessity.

Dr. Godden emphasized both the promise and the danger of these findings. “As the rest of the species faces extinction, these specific bears provide a genetic blueprint for how polar bears might be able to adapt quickly to climate change, making their unique genetic code a vital focus for conservation efforts.” Yet the warning was equally clear: “However, we cannot be complacent. This offers some hope but does not mean that polar bears are at any less risk of extinction. We still need to be doing everything we can to reduce global carbon emissions and slow temperature increases.”

The broader context paints a sobering picture. More than two-thirds of polar bears are predicted to vanish by 2050, with complete extinction expected by the century’s end. Their main obstacle is the same warming trend that appears to be stirring their DNA into action.

Tracing the Hotspots of Change

To understand how profound the genetic shifts might be, the UEA team looked deeper into the polar bear genome. “We identified several genetic hotspots where these jumping genes were highly active, with some located in the protein-coding regions of the genome, suggesting that the bears are undergoing rapid, fundamental genetic changes as they adapt to their disappearing sea ice habitat,” Dr. Godden said.

These hotspots were discovered using RNA sequencing data from a previous University of Washington project, which had identified the southeastern population as genetically distinct from the northeastern group. That earlier study revealed that the two populations diverged around 200 years ago—an eye blink in evolutionary time. The new study builds on this foundation by observing not just that the bears differ, but how quickly and dramatically their genes may be shifting under present conditions.

Working with samples from 17 adult bears—12 from the northeast and 5 from the southeast—the researchers pieced together a picture of how climate, diet, and genetic architecture intertwine. The southeastern bears, living on the edge of habitability, may be engaging in a form of genetic triage, with jumping genes acting as emergency editors of their DNA.

Why This Research Matters

This research offers a rare, detailed glimpse into how a species might be attempting to rewrite its biological fate. The southeastern Greenland bears are not thriving; they are improvising. Their genome is shifting in ways that hint at both the power and the limits of biological resilience.

Understanding these changes matters because it allows scientists to identify which polar bear populations may have the best chance of adapting and which are most vulnerable as the Arctic continues to warm. It also highlights the urgency of conserving genetic diversity across the species. If one group has stumbled upon an adaptive strategy encoded in their DNA, that knowledge could be essential for protecting the species as a whole.

Dr. Godden hopes the work will spark further investigation across the roughly 20 polar bear sub-populations worldwide. As she put it, “I also hope this work will highlight the urgent need to analyze the genomes of this precious and enigmatic species before it is too late.”

In the end, the study reveals a species in motion—not across ice sheets, but within its own cells. The polar bear’s future may depend on how fast and how far these jumping genes can carry it.

More information: Diverging transposon activity among polar bear sub-populations inhabiting different climate zones, Mobile DNA (2025). link.springer.com/article/10.1 … 6/s13100-025-00387-4