Our immune system is an ever-watchful guardian, trained to spot danger at the molecular level. For this vigilant army, naked RNA is a blaring alarm — a molecular calling card of viruses and bacteria like measles, influenza, SARS-CoV-2, or rabies. The moment it sees RNA where it doesn’t belong, it mobilizes an attack.

But here’s the catch: every cell in our body also has RNA. It’s essential for life, acting as the messenger that carries genetic instructions from DNA to the protein-making machinery. If our immune system attacked all RNA, it would destroy us from within. So, how does it tell friend from foe?

The Mystery of RNA Disguise

For years, scientists puzzled over how the immune system avoids attacking our own RNA, even when it’s displayed openly on the surface of cells. “Recognizing RNA as a sign of infection is problematic, as every single cell in our body has RNA,” explains immunologist Vijay Rathinam from the University of Connecticut School of Medicine. The question wasn’t just academic — it was vital to understanding autoimmune diseases, in which the immune system turns against the body.

A clue came from earlier research led by Ryan Flynn at Boston Children’s Hospital and Carolyn Bertozzi at Stanford University. They discovered that many RNAs in our cells are decorated with sugars, forming glycosylated RNAs or glycoRNAs. These sugarcoated molecules sit on cell surfaces, visible to immune cells — yet, mysteriously, they don’t trigger an immune attack.

The Experiment That Revealed the Trick

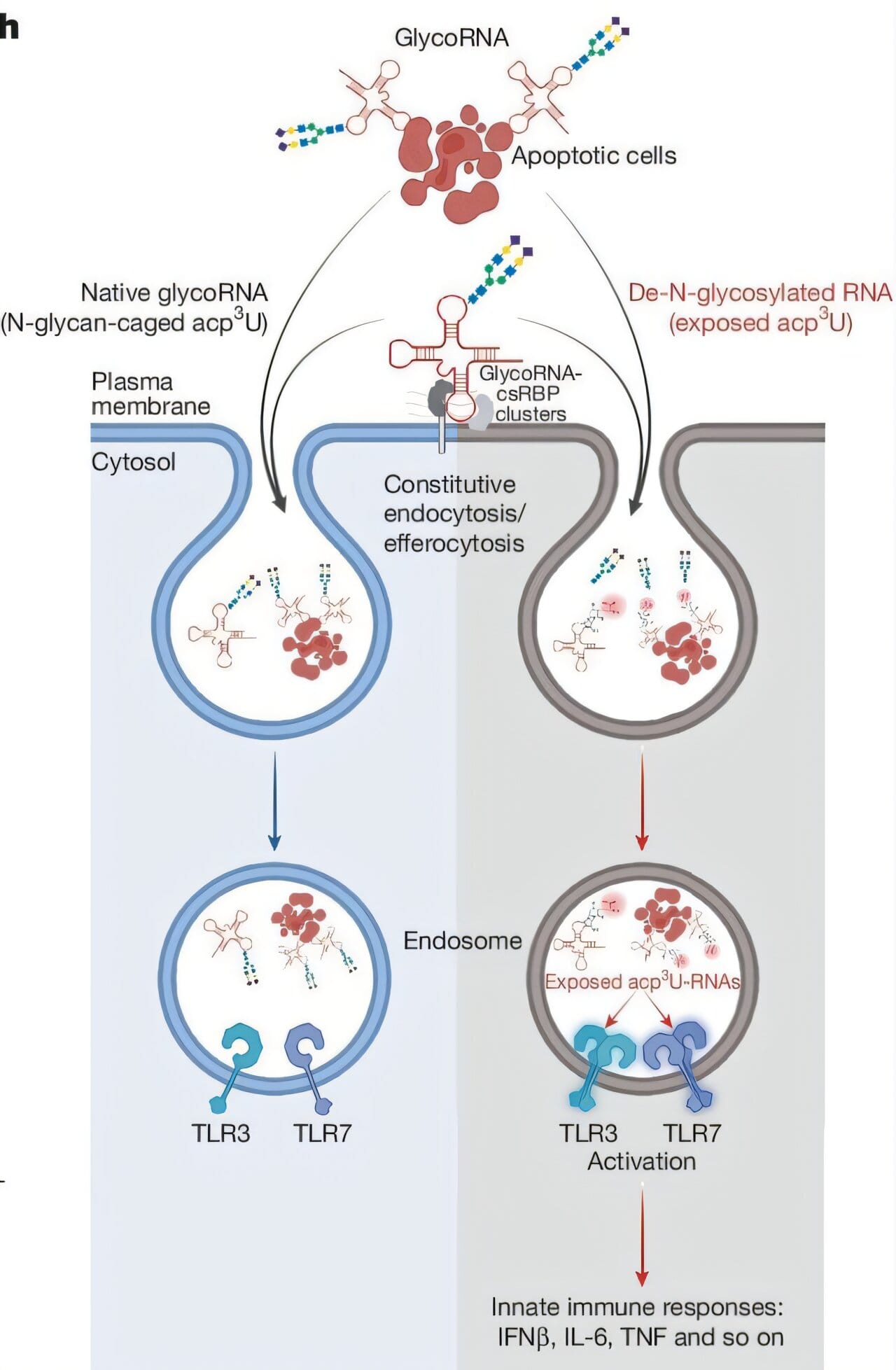

To test whether these sugary decorations acted as protective camouflage, Rathinam’s team conducted a revealing experiment. Vincent Graziano, a Ph.D. student in Rathinam’s lab and lead author of the study, took glycoRNA from human cell cultures and blood samples, carefully removed the sugar layer, and reintroduced the stripped RNA into cells.

The immune system’s response was immediate and aggressive. Without its sugarcoat, the RNA was treated like an intruder. But when left sugarcoated, the same RNA passed unnoticed, like a friend walking through a guarded gate with the right credentials.

“The sugarcoating hides our own RNA from the immune system,” Rathinam says. This means glycosylation isn’t just decorative — it’s a biological security measure, a way for cells to signal, “I belong here. Don’t shoot.”

Why This Matters for Health and Disease

The discovery carries profound implications for understanding autoimmune conditions like lupus, in which the immune system reacts to the body’s own RNA and dead cells. Normally, when cells die and are cleaned up by immune cells, sugarcoated RNA prevents unnecessary inflammation. But if something disrupts this glycosylation process, the immune system could misinterpret self-RNA as a viral signal — potentially triggering chronic inflammation and autoimmunity.

The research, published in Nature, offers a fresh lens for looking at diseases in which the immune system’s “friend or foe” recognition breaks down. It also hints at potential new therapies: if scientists can restore or mimic RNA sugarcoating in patients with autoimmune diseases, they might be able to reduce harmful immune reactions without shutting down the body’s entire defense system.

A Hidden Language of the Cell

In the grand conversation between our cells and our immune system, sugar on RNA acts like a subtle dialect — a molecular “don’t attack” signal that keeps peace in our tissues. Understanding this sugar language opens new doors to medicine, from autoimmune therapy to transplant science.

What’s remarkable is that this protective strategy has likely been with us for millions of years, quietly keeping our immune systems from waging war against the very bodies they protect. And now, thanks to a combination of curiosity, persistence, and molecular detective work, we can finally see how our cells pull it off.

More information: Vincent R. Graziano et al, RNA N-glycosylation enables immune evasion and homeostatic efferocytosis, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09310-6