Some 4.6 billion years ago, Earth was a place of relentless chaos. Asteroids hammered its surface. Temperatures soared high enough to melt rock into a global ocean of magma. Nothing resembling an ocean or even a raindrop could survive there. Water, if present at all, would have been blasted into vapor and lost to space. Yet today, more than two-thirds of the planet is covered in blue. How that transformation happened remains one of the great puzzles of planetary science.

A new study led by Prof. Du Zhixue from the Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry of the Chinese Academy of Sciences offers a striking answer. The team reports that Earth’s earliest water may have survived not on the surface, but deep underground—hidden within the very minerals that crystallized as the planet cooled. Their findings, published in Science, reimagine the earliest chapters of Earth’s history by uncovering a powerful water-holding mechanism buried hundreds of kilometers below our feet.

The Hidden Wells Beneath a Molten World

For decades, researchers believed the deep mantle—especially the lower mantle—was almost entirely dry. Previous laboratory experiments seemed to support that idea, showing that bridgmanite, the dominant mineral at depths beyond 660 kilometers, could store only small traces of water.

But the new study overturns this long-standing view. The researchers reveal that bridgmanite can behave like a microscopic “water container,” holding water far more effectively than earlier experiments suggested. Crucially, its capacity to store water appears to increase dramatically with temperature. And early Earth was very, very hot.

This means that as the magma ocean began to solidify, bridgmanite forming in the deep mantle could have trapped large quantities of water from the molten interior. According to the team, this early-retained water may have played an essential role in reshaping the planet from a global furnace into a world that could eventually host oceans, atmosphere, and life.

The Experiments That Recreated Earth’s Fiery Depths

Understanding the behavior of minerals under deep-Earth conditions is notoriously challenging. The lower mantle endures pressures and temperatures that are nearly impossible to recreate on the surface. Earlier experiments, limited by lower temperatures, may have significantly underestimated bridgmanite’s water-storage capabilities. Prof. Du’s team aimed to test the mineral under conditions that truly matched the deep mantle.

To do this, they engineered a diamond anvil cell experiment equipped with laser heating and high-temperature imaging—technology capable of generating conditions approaching those at depths greater than 660 kilometers. Their self-developed device pushed temperatures to an extraordinary ~4,100 °C, enabling precise measurements of mineral behavior in extreme environments.

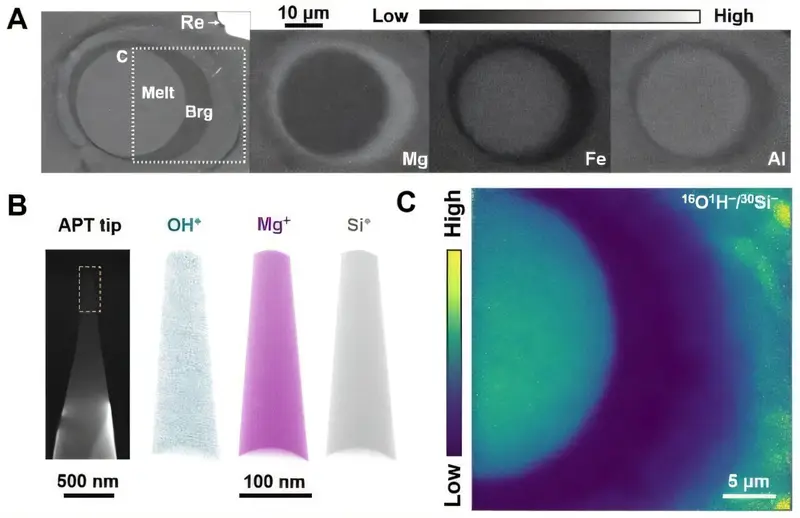

Reaching these temperatures was only half the challenge. Detecting water inside microscopic bridgmanite grains—each smaller than one-tenth the width of a human hair—required new analytical approaches. The team used the most advanced tools available at GIGCAS, including cryogenic three-dimensional electron diffraction and NanoSIMS, technologies sensitive enough to detect water at concentrations of just a few hundred parts per million.

They also collaborated with Prof. Long Tao from the Institute of Geology of the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences to apply atom probe tomography (APT). Combined, these techniques acted like ultra-high-resolution chemical CT scanners and mass spectrometers for the mineral world. They allowed the researchers to visualize water distribution inside individual mineral samples and confirm that water was not merely trapped in cracks, but “structurally dissolved” in bridgmanite itself.

A Giant, Invisible Ocean in the Deep Earth

With these tools, the team constructed an entirely new picture of the early mantle. Their experiments showed that bridgmanite’s water partition coefficient—its ability to attract and hold water—rises sharply with temperature. In other words, the hotter the environment, the more water the mineral can lock away.

Armed with these measurements, the researchers modeled the crystallization of the early magma ocean. Their simulation yielded a striking result: as the molten Earth cooled, bridgmanite at depth became the largest water reservoir in the entire solid mantle. Its storage capacity, they estimate, could have been five to 100 times greater than previous assessments.

The total water held in the solid mantle during this early phase may have been between 0.08 and one times the volume of all modern oceans. This massive water reserve, buried deep below the cooling crust, challenges the idea that early Earth lost most of its water or received it only later from comets or asteroids. Instead, it suggests that a significant fraction of Earth’s original water never left at all—it simply migrated inward and hid.

The Quiet Engine Beneath Earth’s Transformation

What happened to this water over time? The answer points toward a slow geological cycle that may have shaped the planet’s entire evolution.

Water trapped in the deep mantle would not remain static. The researchers describe it as acting like a “lubricant” for the planet’s internal engine. By lowering the melting point and viscosity of mantle rocks, this water helped set the stage for mantle convection and plate motion—processes that drive volcanism, mountain building, and the recycling of minerals through Earth’s crust.

As mantle convection circulated material upward, some of this ancient water would have been gradually “pumped” back to the surface through volcanic activity. Over millions of years, this released water contributed to the formation of the atmosphere and the world’s first oceans. The scientists describe it as the “spark of water” sealed into Earth’s structure from the beginning—a spark that ultimately ignited the transition from a molten inferno to a blue planet.

Why This Discovery Matters

Understanding where Earth’s water came from is more than a matter of geological curiosity. It speaks to one of the most fundamental questions in planetary science: how does a barren rock evolve into a habitable world?

This study provides a new pathway for that transformation. By demonstrating that bridgmanite could store and preserve water even during early Earth’s hottest phases, the research offers a compelling explanation for how water survived the planet’s violent infancy. It also reframes the deep mantle not as a dry, inert layer but as a dynamic reservoir capable of storing and releasing water across billions of years.

These insights reshape our understanding of early planetary evolution and highlight the hidden connections between deep interior processes and the surface environments where oceans, climates, and ecosystems emerge. If water was locked into Earth’s structure from the beginning, then the story of life’s origins is intertwined with the story of the planet’s internal architecture. In this way, the research uncovers not only a new scientific mechanism, but also a new narrative of Earth’s earliest identity—one in which the seeds of habitability were embedded deep within the molten planet long before the first ocean formed.

More information: Wenhua Lu et al, Substantial water retained early in Earth’s deep mantle, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adx5883. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adx5883

Michael Walter, Deep mantle clues to Earth’s watery beginning, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.aed3351 , www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aed3351