High in the rugged peaks of the Chilean Andes, glaciers once flowed like icy rivers, pressing down upon mountains that seemed timeless and immovable. Yet beneath that tranquil white armor, a different world seethed—a world of molten rock, imprisoned gases, and forces biding their time.

Now, as climate change accelerates the retreat of glaciers worldwide, scientists warn that these sleeping giants beneath the ice may be stirring. New research, to be presented at the Goldschmidt Conference in Prague on July 8, reveals that melting glaciers could trigger more frequent and more explosive volcanic eruptions in the coming centuries.

The findings extend a phenomenon long recognized in Iceland to the vast, glacier-capped volcanoes of continental regions, suggesting that a hidden consequence of climate change may soon emerge in dramatic bursts of fire and ash.

The Silence Beneath the Ice

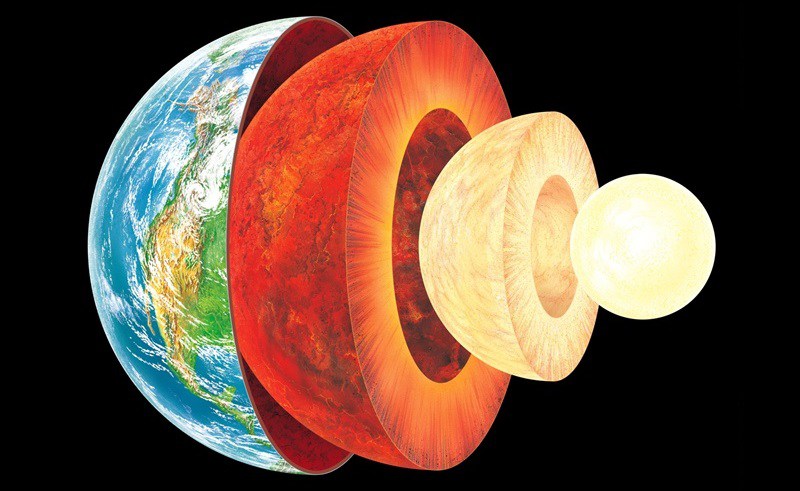

To the casual observer, a glacier appears eternal—a shimmering monument to cold and time. Yet glaciers are not merely passive blankets of ice. They exert immense weight on the rocks beneath them, pressing down like a cosmic paperweight on the restless magma hidden below.

During the last ice age, around 26,000 to 18,000 years ago, the Patagonian Ice Sheet lay thick over southern Chile’s volcanoes, including Mocho-Choshuenco—a now dormant volcano that once roared with molten fury. Under that icy crush, the volcano’s eruptions were muted. The glacier’s mass acted like a cork in a shaken bottle, keeping volatile gases trapped deep underground.

But as the ice melted, the cork came loose.

A Glacial Trigger for Volcanic Fury

Pablo Moreno-Yaeger, from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, leads the team behind this new study. By analyzing crystals locked in volcanic rocks and using precise argon dating, Moreno-Yaeger and his colleagues reconstructed the secret history written in Chile’s mountains.

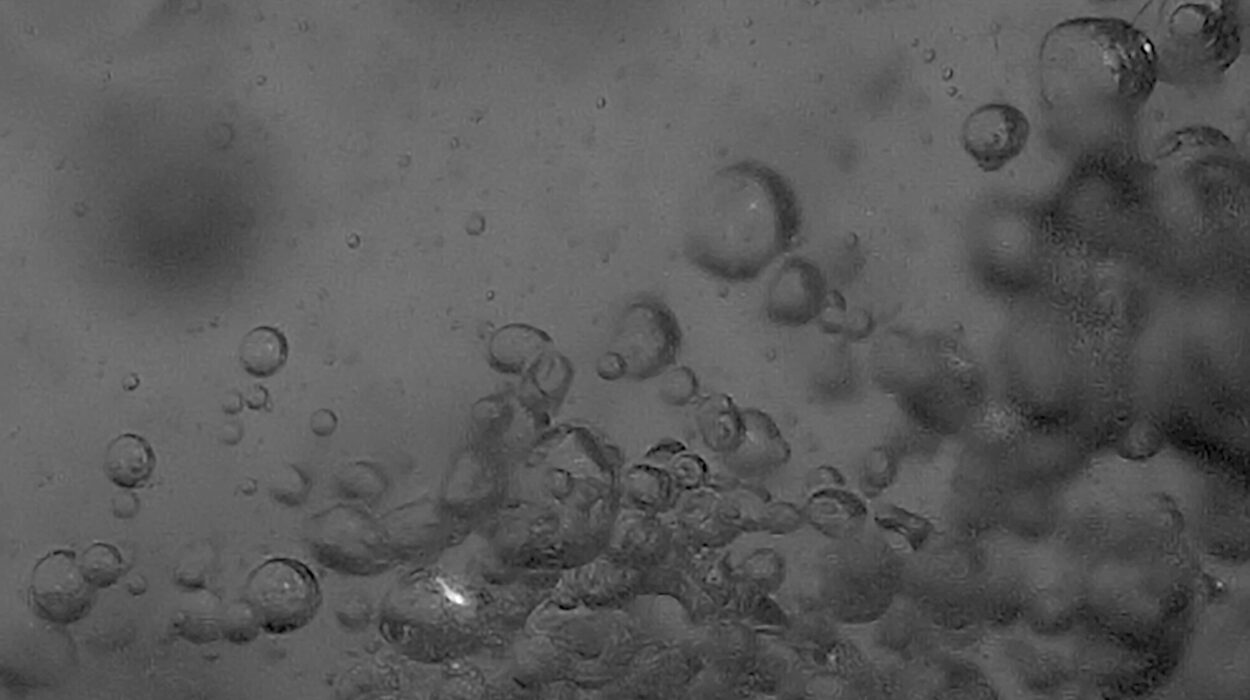

They discovered that as glaciers retreated at the end of the last ice age, a sudden loss of pressure allowed gases within magma to expand violently. The Earth’s crust, once compressed under kilometers of ice, relaxed and fractured, opening pathways for magma to surge upward. Eruptions followed—some explosive enough to shape entire volcanoes.

“Glaciers tend to suppress the volume of eruptions from the volcanoes beneath them,” Moreno-Yaeger explained. “But as glaciers retreat due to climate change, our findings suggest these volcanoes go on to erupt more frequently and more explosively.”

It’s a scenario akin to shaking a bottle of soda under pressure and then popping the cap. The release is swift—and sometimes spectacularly destructive.

Beyond Iceland: A Global Threat Looming

Scientists have long known about this glacier-volcano connection in Iceland, where retreating ice sheets have coincided with increased volcanic activity since the 1970s. But Moreno-Yaeger’s research is among the first to explore this dynamic in continental volcanic systems.

“Our study suggests this phenomenon isn’t limited to Iceland,” he said. “It could also occur in Antarctica. Other continental regions, like parts of North America, New Zealand, and Russia, also now warrant closer scientific attention.”

Antarctica, home to hundreds of subglacial volcanoes, is of particular concern. As glaciers there melt at unprecedented rates, scientists fear a cascade of eruptions could follow—introducing not only local hazards but potentially global consequences.

Volcanoes, Climate, and a Dangerous Feedback Loop

At first glance, volcanic eruptions might seem to counteract climate change. Explosive eruptions can hurl aerosols high into the atmosphere, reflecting sunlight and briefly cooling the planet. After Mount Pinatubo erupted in the Philippines in 1991, global temperatures dipped by about 0.5°C for a few years.

Yet the story doesn’t end there.

“Over time, the cumulative effect of multiple eruptions can contribute to long-term global warming because of a buildup of greenhouse gases,” Moreno-Yaeger warned. “This creates a positive feedback loop, where melting glaciers trigger eruptions, and the eruptions in turn could contribute to further warming and melting.”

It’s a vicious cycle: warming melts ice, releasing the volcanoes, whose eruptions could then add to the greenhouse gases heating the planet.

A Race Against Geological Time

The volcanic response to melting ice can happen with startling speed—at least in geological terms. Yet the changes brewing in magma chambers unfold over centuries, creating a slim window for scientists to monitor, study, and prepare.

“Our work shows that the processes leading to increased volcanic activity are gradual,” Moreno-Yaeger said. “That gives us some time to understand which volcanoes might be most at risk and to develop early warning systems.”

But time may not be on our side if climate change continues at its current pace.

Watching the Mountains for Signs of Fire

From the icy flanks of Mocho-Choshuenco to the buried peaks beneath Antarctica’s glaciers, Earth’s volcanoes are sending subtle signals of the changes to come. Crystals in ancient lava flows whisper stories of ice and fire, of pressure released and worlds remade.

Scientists now listen to those whispers with renewed urgency.

As the world warms, the line between ice and magma grows thinner. What happens next may depend not only on forces deep within the planet but also on the choices humanity makes above the surface.

The volcanoes, after all, are waiting.

Reference: Conference abstract: Expansion and contraction of the Patagonian ice sheet and it’s influence on magma storage beneath Mocho-Choshuenco volcano. zenodo.org/records/15021753