There’s a question that haunts childhood curiosity and academic debates alike—a question whispered in museums, argued in classrooms, and mulled over late at night under the stars: Did we really evolve from apes?

It’s an innocent question, but it opens a door to a story far more complex and astonishing than most people imagine. The short answer is no, we didn’t evolve from the apes you see in zoos today. But we do share a common ancestor. That single truth has set off a cascade of scientific discovery over the last two centuries—a puzzle stretching across ancient bones, DNA sequences, cave paintings, and the very structure of our brains.

It’s a story not just of biology but of time, migration, survival, and identity. To understand who we are, we must look back—not to a single missing link, but to a sprawling, tangled tree whose roots go deep into deep time.

The Misunderstood Tree of Life

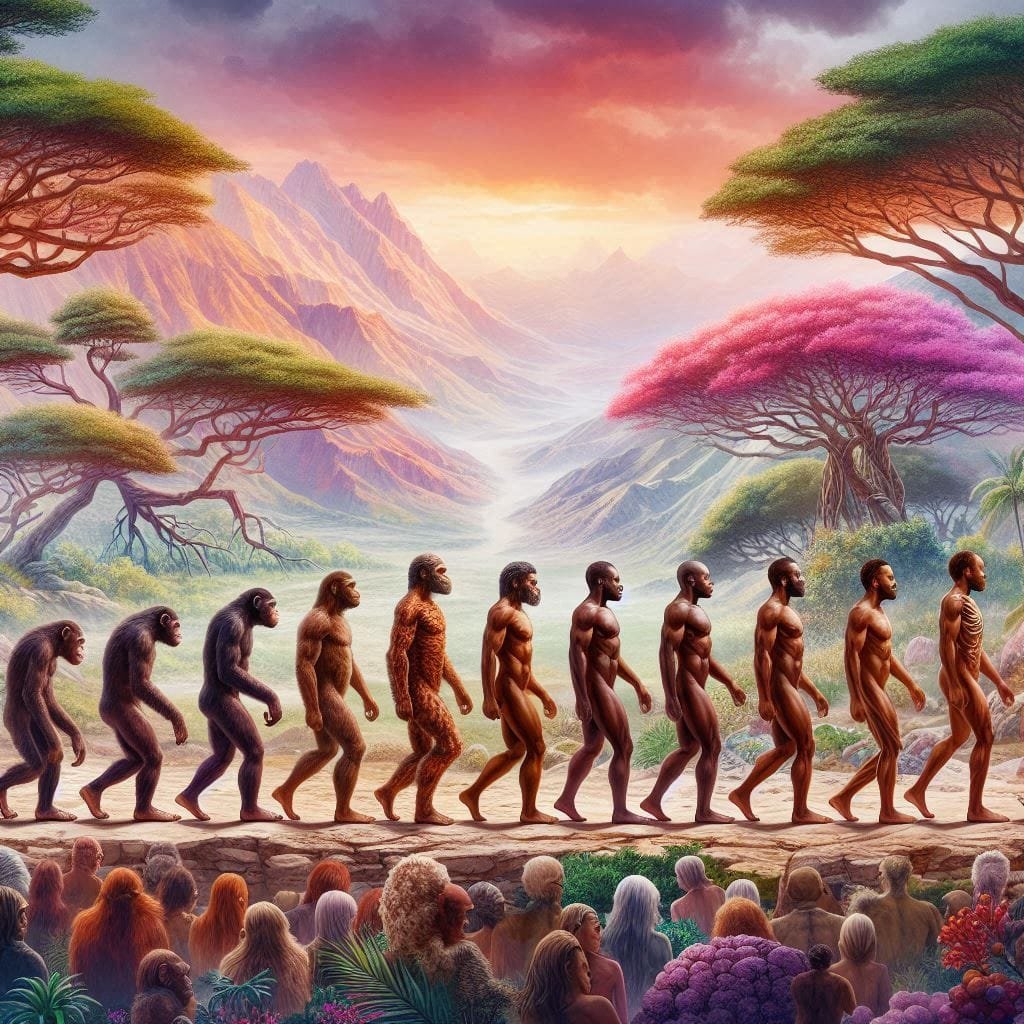

The phrase “humans evolved from apes” makes it sound like one day a chimpanzee stood up, lost some fur, and became a caveman. But evolution is not a ladder with apes on the bottom and humans on the top. It is a tree, and we are one of its many branches.

Humans and modern apes like chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans all descend from a common ancestor that lived around six to eight million years ago. This ancestor was neither a human nor a chimp, but something different—a species now extinct, which branched off into various lineages. One lineage led to us. Another led to today’s chimpanzees.

To say we evolved from apes is like saying cousins come from each other. No, cousins share a grandparent, just as we and the other great apes share an evolutionary grandparent of sorts. And that ancient relative was more like an ape than a modern human, yes—but it wasn’t any of the apes alive today.

So the real story isn’t about apes becoming human. It’s about two evolutionary siblings who each went their own way, down paths shaped by time, climate, chance, and adaptation.

Echoes in Stone and Bone

The Earth itself has preserved pieces of our story—fossils that whisper across time. In Africa, the bones of our ancestors have surfaced slowly, dusted off by patient hands, carried out of caves and sandstone cliffs like sacred texts.

One of the most famous of these is “Lucy,” the 3.2-million-year-old Australopithecus afarensis skeleton discovered in Ethiopia in 1974. At first glance, Lucy’s bones looked primitive—long arms, curved fingers, a small brain. But her pelvis and leg bones told a different story: she walked upright. She was a biped.

Walking on two legs was one of the first great leaps on the road to becoming human, long before big brains or language. Why our ancestors started walking upright remains debated. Maybe it freed their hands to carry tools or food. Maybe it helped them see over tall grass, or travel long distances in a changing climate.

What’s certain is that bipedalism split us from our tree-swinging relatives. Once that fork in the evolutionary road was taken, there was no turning back.

From Shadows to Faces

As more fossils emerged—Homo habilis, Homo erectus, Homo naledi—a picture began to take shape. It wasn’t a straight line of descent, but a branching bush of humanity, with many species living and dying out before Homo sapiens appeared.

These early humans made tools, hunted in groups, cared for each other. Some had brains half the size of ours but showed signs of cooperation and planning. They lived in a world full of predators and uncertainty, yet they began to shape that world with fire, shelters, and communities.

Then came Homo sapiens—us. We emerged in Africa roughly 300,000 years ago. Compared to our ancestors, we were leaner, smarter, more adaptable. We painted on cave walls. We made music. We crossed rivers and climbed mountains. We imagined gods and invented mathematics.

But we weren’t alone.

The Ghosts in Our Genes

It was once believed that modern humans outcompeted and replaced all other hominin species. But then the genomes told a deeper truth.

In 2010, the sequencing of Neanderthal DNA revealed that modern non-African humans carry 1% to 2% Neanderthal genes. That meant our ancestors didn’t just wipe them out—they mated with them.

Further studies uncovered traces of another mysterious cousin—Denisovans—who left genetic fingerprints in the peoples of Oceania and parts of Asia. The idea of a pure, linear human lineage was gone. In its place stood something far richer: a web of interbreeding, cooperation, conflict, and survival.

We are not the lone survivors of some evolutionary contest. We are the result of entanglement, a fusion of multiple hominin lines. The ghosts of other humans live in our very blood.

What Made Us Human?

Despite all this shared ancestry, one species came to dominate—Homo sapiens. Why?

Theories abound. One possibility is that we developed a kind of social intelligence unparalleled in the animal world. We didn’t just live in groups—we told stories, created shared myths, passed down knowledge through language.

This ability to create shared beliefs may have given us a survival advantage. While Neanderthals were strong and smart, they may have lacked the same level of symbolic thinking. A group of humans could organize around a vision—a hunt, a ritual, a goal. They could imagine the future. They could mourn the past.

There’s also evidence that humans were more flexible. We adapted to deserts, tundras, forests, coasts. We built rafts to cross seas. We invented tools not just for one task, but for thousands.

That adaptability proved decisive. When climates shifted, when food ran out, when new lands beckoned—we moved, we adapted, we endured.

The Language of Evolution

The theory of evolution, first laid out by Charles Darwin in On the Origin of Species, provides the framework for understanding all of this. But evolution isn’t a theory in the everyday sense—it’s the backbone of modern biology, supported by countless lines of evidence.

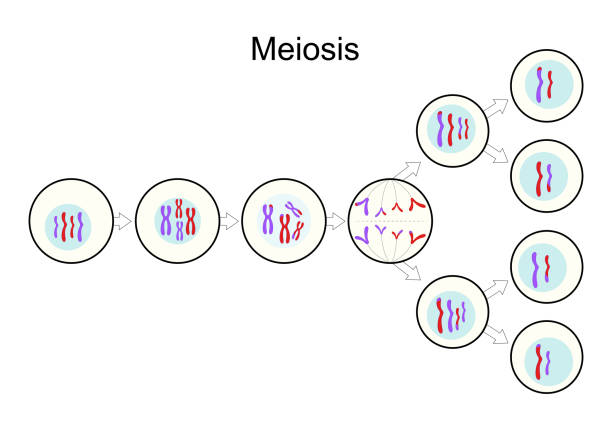

Fossils show gradual changes over time. Comparative anatomy reveals shared structures. Embryology shows similar development in different species. And perhaps most convincingly, DNA shows the shared genetic code among all life.

Our DNA is 98.8% identical to that of chimpanzees. That small difference accounts for our unique capacities, but it also testifies to our shared heritage.

The idea that we are “just animals” is often used as a criticism of evolution. But the truth is more beautiful and more humbling. We are animals, yes—but animals capable of asking where we came from. That in itself is a kind of miracle.

The Fear and Wonder of Evolution

Why does the idea of evolution still stir so much controversy?

For some, it challenges deeply held religious beliefs about the creation of humanity. For others, it seems to undermine human uniqueness. But evolution doesn’t reduce us—it reveals how extraordinary we are, not in opposition to nature, but as its flowering.

Evolution explains how a lump of carbon and water could become self-aware. It tells us how a species of upright apes learned to paint the Sistine Chapel, fly to the moon, and write symphonies.

It reminds us that we are not separate from the world, but shaped by it—and responsible for it.

Are We Still Evolving?

The answer is yes. Evolution never stopped.

Human bodies are still adapting—some populations have developed resistance to diseases, others can digest milk into adulthood, or thrive at high altitudes. But more subtly, our culture, technology, and environment are now the most powerful forces shaping our evolution.

We may soon evolve not just biologically, but technologically—through genetic engineering, cybernetics, artificial intelligence. The lines between natural and artificial evolution are beginning to blur.

In a sense, we are becoming the authors of our own evolutionary story.

Conclusion: More Than Apes

So, did humans evolve from apes?

Not exactly. We share a common ancestor with apes, one that lived millions of years ago. Since then, we’ve followed our own path—a winding, dramatic, sometimes brutal path that led to art, science, language, empathy, and curiosity.

We are not descended from chimpanzees or gorillas. But we are their cousins. We share with them not only genes, but also emotions, behaviors, and social bonds. We share with all life on Earth a deeper kinship written in DNA.

And the story isn’t over.

Each child born today inherits not just genes, but the wonder of a species that looked back through time and dared to ask: Where did we come from? And what does it mean to be human?

To understand evolution is not to lose the mystery of life. It is to find that mystery in every cell, every bone, every heartbeat. It is to realize that we are stardust, yes—but stardust that learned to ask questions.

And that may be the most human thing of all.