In 1859, Charles Darwin cracked open the mystery of life with his earth-shaking theory of evolution by natural selection. With On the Origin of Species, he didn’t just introduce a theory—he lit a fire. Over the next century, biologists, paleontologists, and geneticists would dig through the past, mapping the tree of life from its deepest roots to its blossoming branches.

But even as the fossil record thickened and genomes revealed our hidden histories, one phrase remained stuck in the popular imagination: the missing link. It’s a term that evokes mystery, frustration, and a deep desire to know exactly how we became who we are. The phrase carries the hope that somewhere in the dust of ages lies a single fossil, a perfect transitional form that bridges what seem to be impossible evolutionary gaps.

Science, of course, is more nuanced. Evolution is not a ladder with missing rungs; it’s a tree with millions of branches, many broken or buried. Still, the idea of the “missing link” endures—especially in discussions about human evolution. And while many supposed gaps have narrowed with new discoveries, there are still stubborn blind spots in the evolutionary story. Some are physical. Some are molecular. Some lie in the depths of consciousness itself.

And they all whisper the same haunting question: What does science still not know about how we got here?

When Bones Aren’t Enough

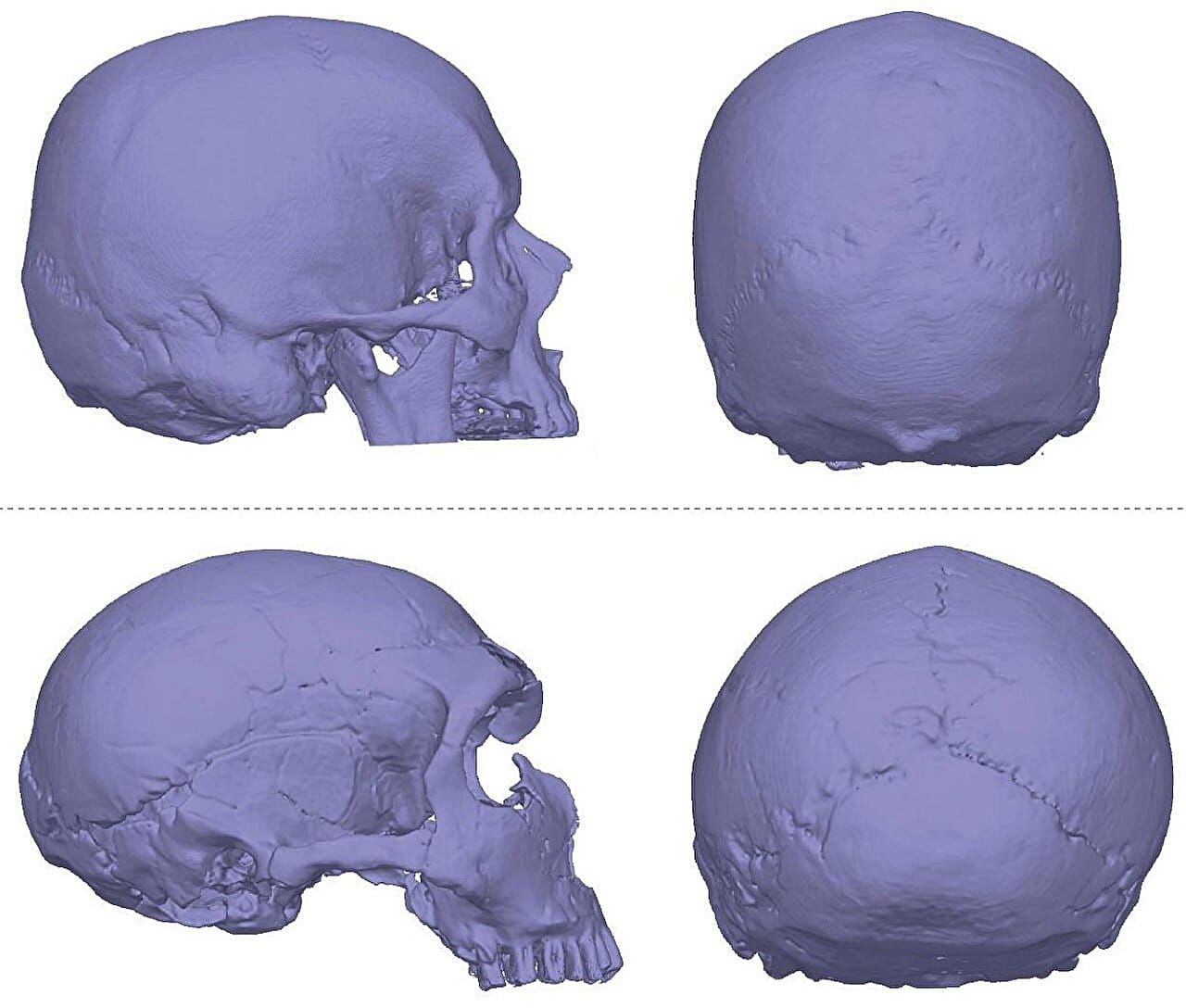

Fossils are fragile ambassadors from the past. They speak to us in fragments—jawbones, skullcaps, footprints preserved in ancient ash. Each new find can be a revelation or a red herring. The fossil record is famously incomplete, not because evolution didn’t happen, but because fossilization is rare. Soft tissues rot. Skeletons are scattered. Most creatures vanish without a trace.

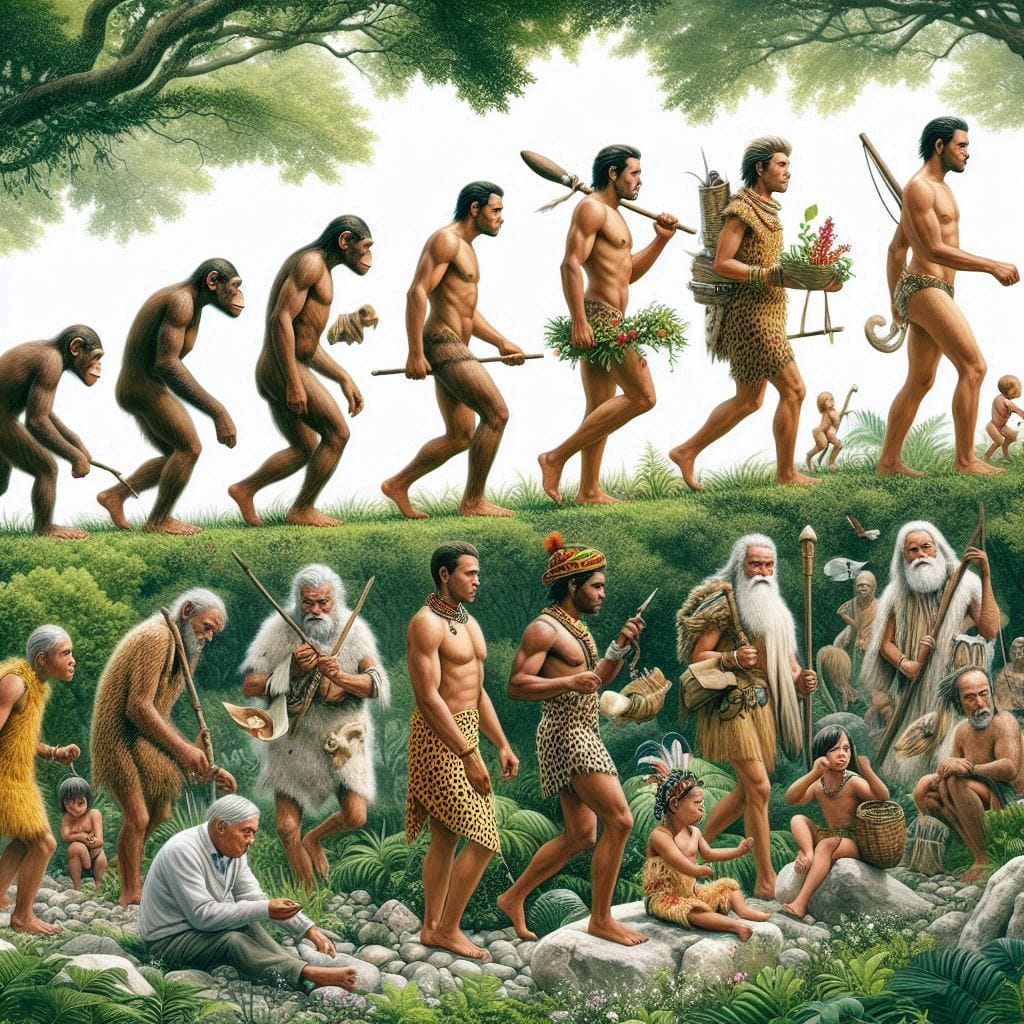

Yet, despite these challenges, we’ve unearthed a surprisingly rich record of transitional forms. Archaeopteryx showed how birds may have evolved from reptiles. Tiktaalik, a flat-headed fish with limb-like fins, filled in a gap between sea and land. Australopithecus afarensis—famously nicknamed “Lucy”—walked upright long before humans ever dreamed of cities or tools.

These are not “missing links” in the sense of a perfect, linear path, but they are powerful clues in the messy mosaic of life. Still, gaps remain. And nowhere are they felt more acutely than in the story of us—humans.

For decades, scientists searched for a direct ancestor of both apes and humans—a so-called “missing link” that could explain the fork in our evolutionary path. Many candidates have been proposed: Sahelanthropus tchadensis, a 7-million-year-old skull found in Chad; Ardipithecus ramidus, with a strange blend of ape-like arms and human-like pelvis; Homo habilis, the so-called “handy man” who may have been the first to wield tools.

Yet none are a perfect fit. The branches twist. Some lineages end abruptly. Others branch off in unexpected directions. The idea of a single missing link—one magic fossil to explain it all—now seems too simplistic. Evolution doesn’t deal in perfection. It deals in chance, in survival, in adaptation. And yet, the gaps still beckon.

Genes Don’t Lie—Except When They Do

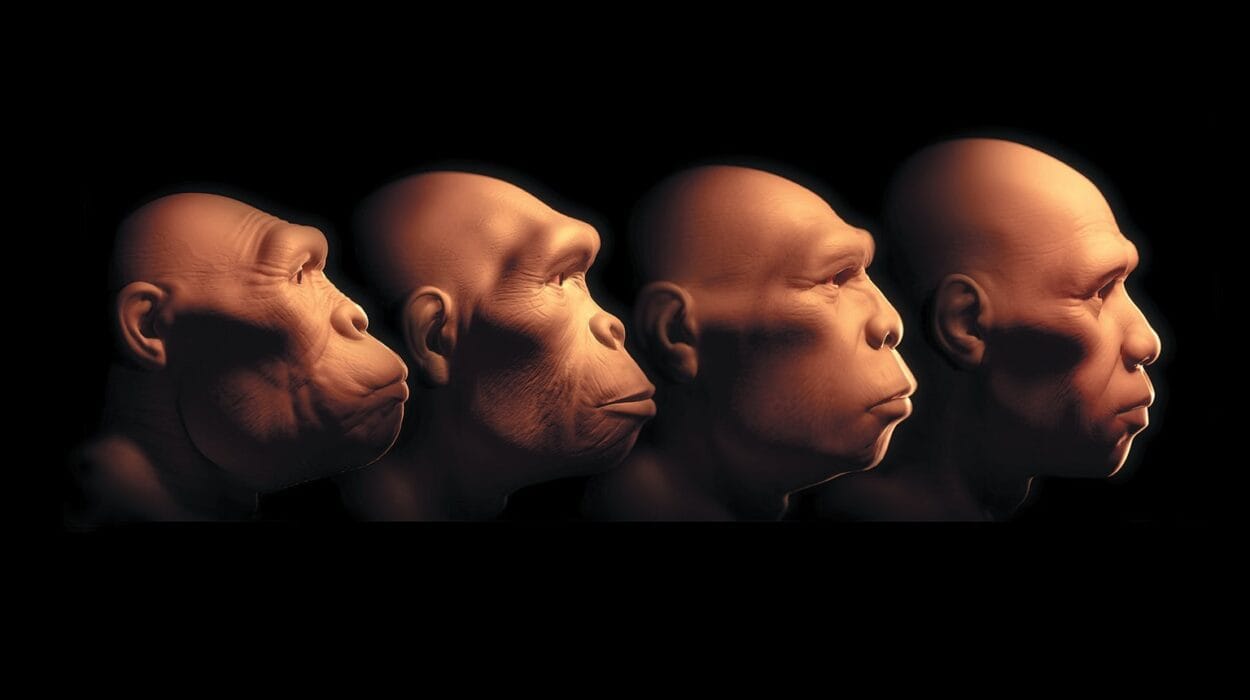

In the age of DNA, fossils are no longer the only story. Our genomes carry an evolutionary record written in code—mutations, duplications, ancient insertions of viral DNA. Comparative genomics lets scientists trace lineages with unprecedented clarity. Humans share about 98.8% of our DNA with chimpanzees, our closest living relatives. The differences, while seemingly small, have profound effects.

But here, too, are mysteries.

Why do such small genetic differences yield such enormous cognitive, behavioral, and social divergence? What makes the human brain so radically different? Why did language, abstract thought, and art emerge in humans but not in other primates with almost identical genes?

There are no clear-cut answers. Some theories suggest changes in regulatory genes—those that control when and how other genes are expressed—may have played a role. Others point to a few key genetic mutations, such as in the FOXP2 gene, associated with language development. But the puzzle remains maddeningly incomplete.

And then there are genes we don’t fully understand at all: genes whose function is unclear, or sequences that seem to serve no purpose yet are conserved across species. What secrets do they hold? Are they relics of past evolutionary battles? Are they the shadow of something we once needed, or the blueprint for something still to come?

Genetics has given us powerful tools, but it has also humbled us. The more we learn, the more complex the picture becomes. The story of evolution is not simply about acquiring genes; it’s about how genes interact, how they’re turned on or off, and how they shape behavior in ways we’re only beginning to grasp.

Consciousness: The Ultimate Mystery

Of all the traits that set humans apart, none is more enigmatic than consciousness. The ability to reflect, imagine, empathize, and create is not easily pinned down to a fossil or a gene. It lives in neural circuits, yes—but also in art, in culture, in self-awareness. When did our ancestors become conscious in the way we are today?

The archaeological record shows a slow but steady emergence of symbolic thinking: beads, cave paintings, burial rituals. These acts suggest a mind capable of abstraction and a sense of something beyond the material world. But when did this shift happen? And why?

Some scientists point to the “cognitive revolution” around 70,000 years ago, when Homo sapiens began producing complex tools and art. Others argue that consciousness emerged far earlier, perhaps in Neanderthals or even Homo erectus.

But no fossil shows consciousness. No DNA sequence glows with self-awareness. We are left with indirect evidence—and a profound mystery. Evolution can explain brain size and structure. But the experience of being—of dreaming, fearing, loving—is harder to explain.

Is consciousness an inevitable result of complex neural networks? Or is it an emergent property that arose by accident, like fire from friction? Is it unique to humans, or do other animals possess its spark in ways we fail to recognize?

Science has no definitive answers. The gap between neural activity and subjective experience—the so-called “hard problem” of consciousness—remains one of the deepest mysteries in both biology and philosophy. It is, in its way, the missing link of the mind.

The Cambrian Conundrum

Long before humans or even dinosaurs, another evolutionary puzzle unfolded: the Cambrian explosion.

Around 540 million years ago, life on Earth underwent a dramatic transformation. In a geological blink of an eye—perhaps 20 to 25 million years—most major animal groups appeared in the fossil record. Complex body plans, bilateral symmetry, eyes, skeletons—all emerged rapidly compared to the slow pace of earlier evolution.

Why?

Some scientists suggest environmental triggers: rising oxygen levels, changing ocean chemistry, or the evolution of predation. Others point to genetic innovations, such as the appearance of Hox genes that guide body plan development.

But even with these theories, the speed and diversity of the Cambrian explosion remain surprising. Why did evolution accelerate so dramatically after billions of years of microbial monotony? What combination of factors tipped the scales?

We have fragments of the answer—but not the whole picture. The Cambrian conundrum remains one of evolution’s most intriguing gaps, not because it contradicts the theory, but because it challenges our understanding of its tempo and triggers.

Epigenetics and the Ghost in the Genome

For much of the 20th century, biology followed a simple path: DNA makes RNA makes protein. But today, we know that’s only part of the story.

Epigenetics—the study of changes in gene expression without changes to the underlying DNA sequence—has revolutionized our understanding of heredity. Environmental factors, stress, diet, even trauma can influence how genes are expressed. These changes can sometimes be passed down to future generations.

It raises uncomfortable questions: How much of who we are is written in our DNA, and how much is written in the lives we live?

This plasticity adds a new dimension to evolution. Traits may not need millions of years of genetic change to become prominent. In some cases, they may be shaped by experience, passed down epigenetically, and influence natural selection more rapidly than previously thought.

But this also muddies the waters. Evolution is no longer just a story of mutations and survival—it’s a story of complex feedback loops between genes, environments, and cultures. The simplicity of the “missing link” metaphor begins to unravel in the face of such complexity.

The Puzzle of Bipedalism

One of the earliest markers of human evolution is bipedalism—the ability to walk upright on two legs. It seems simple, even obvious. Yet it represents one of the most profound anatomical shifts in evolutionary history.

Why did our ancestors stand up?

Some theories suggest environmental change: as forests gave way to savannahs, standing upright helped early hominins spot predators or carry food. Others point to thermoregulation—less body surface exposed to the sun—or the freeing of hands for tool use and carrying infants.

But walking upright is costly. It makes childbirth more dangerous. It increases stress on joints. It makes us slower runners compared to four-legged animals. So why did this trait persist—and when exactly did it begin?

Fossils show a mix of walking styles for millions of years. Australopithecus afarensis was fully bipedal yet retained some adaptations for climbing. The transition was not sudden. It was, like much of evolution, a long experiment with many trials and errors.

Still, we don’t fully understand what triggered that first step onto two feet. The missing link in locomotion may lie not in bones, but in behavior and ecology—factors harder to preserve and harder to study.

Why So Many Extinctions, So Few Survivors?

The tree of life is pruned by extinction. Over 99% of all species that ever lived are now gone. Entire lineages vanished, while others adapted, survived, and thrived.

Why us?

Homo sapiens is the only surviving species of the genus Homo. At least six others walked the Earth before us: Homo habilis, Homo erectus, Homo naledi, Homo floresiensis, Homo luzonensis, and the mysterious Denisovans. Some lived in Asia. Some on islands. Some may have buried their dead, made tools, or even spoken rudimentary languages.

Then they were gone.

Did we outcompete them? Interbreed? Wipe them out? Did climate shifts seal their fate? Or were they simply unlucky?

The disappearance of our cousins remains one of the most poignant gaps in our history. In their absence, we are alone—a single twig on a once-thriving branch. The causes are likely multiple. But the story remains incomplete.

Aliens, Gods, and the Lure of the Unknown

The gaps in evolutionary science are fertile ground for speculation. In the absence of certainty, some turn to the supernatural. The idea that a god or gods created humans in their image is a deeply held belief in many cultures.

Others look to the stars. Ancient astronaut theories claim that extraterrestrial beings seeded life or guided human evolution. These ideas, while captivating, are not supported by scientific evidence.

But their popularity underscores a deeper truth: people crave narrative closure. The missing link isn’t just about fossils or genes. It’s about identity. We want to know where we came from, who we are, and whether we are alone in the cosmos.

Science doesn’t offer all the answers—but it offers a method, a candle in the darkness. It tells us that not knowing is not failure, but invitation. Every gap is a question. Every missing link is a chance to look deeper.

What We Still Don’t Know

Despite the dazzling progress of modern science, many questions remain:

- Why did intelligence evolve in the way it did?

- What exactly triggered the cognitive leap to symbolic thought?

- How do genes, environment, and culture interact over generations?

- What lies at the root of consciousness?

- Are we the inevitable result of evolution—or just one lucky accident among many?

These are not idle questions. They shape how we see ourselves, how we treat other species, and how we imagine our future.

The story of evolution is not a solved puzzle. It’s a living narrative, with new chapters written every year by paleontologists brushing dust from ancient bones, geneticists decoding ancient genomes, neuroscientists mapping the mind.

And in the spaces between those chapters, the missing links remain—not as failures of science, but as reminders that the story is still unfolding.