Rome once called itself eternal, and for centuries, it seemed true. The Roman Empire stretched from the misty hills of Britain to the deserts of Egypt, from the Pillars of Hercules in Spain to the fertile lands of Mesopotamia. Its legions marched with thunderous precision, its aqueducts carried water across impossible distances, and its cities dazzled with marble and monuments. The Roman people believed they had mastered the world, bending nature, nations, and even time itself to their will.

Yet, in the shadow of triumph, seeds of decline took root. The fall of Rome was not the catastrophe of a single night, as legends sometimes paint it, but rather a slow unraveling—a long twilight marked by crises, battles, betrayals, and transformations. By the 5th century CE, the once-mighty empire in the West was fractured, vulnerable, and ultimately collapsed, leaving behind ruins and legends. But why did this happen? Why did one of history’s greatest empires fall?

The answer lies not in a single cause but in a convergence of forces—political, military, economic, cultural, and environmental. To understand Rome’s fall is to understand the fragility of power and the universal truth that even the greatest civilizations are not immune to decline.

The Weight of Greatness

At its height, the Roman Empire was immense, a patchwork of cultures, languages, and landscapes held together by roads, armies, and law. But the very size that gave Rome its glory also made it vulnerable. Governing such vast territory required extraordinary resources and constant vigilance. Armies had to patrol distant frontiers. Administrators had to collect taxes, enforce laws, and ensure food supply. Communication stretched across thousands of miles, making swift responses to crises nearly impossible.

Empire was Rome’s strength—and its weakness. The grandeur of Rome masked the fact that it was often overextended, stretched thin across lands that had little in common except the authority of the emperor. The larger Rome grew, the harder it became to manage, and cracks in its foundation widened with each passing century.

The Crisis of Leadership

One of the greatest challenges that doomed Rome was its inability to ensure stable leadership. Unlike monarchies where succession was clear, Rome’s system of imperial succession was often chaotic and violent. Emperors were murdered by their own guards, replaced by generals who seized power through civil war. The infamous Year of the Five Emperors (193 CE) and the Crisis of the Third Century (235–284 CE), when over 20 emperors ruled in rapid succession, showcased how fragile the imperial office could be.

A state can endure many hardships, but constant instability at the top erodes confidence, weakens institutions, and invites rebellion. Roman emperors were often too busy fighting rivals for the throne to govern effectively, leaving economic troubles and military threats unresolved. The empire became a stage for power struggles rather than a stable realm.

The Economic Strain

Rome’s wealth was legendary, built on conquest, tribute, and trade. Gold from Spain, grain from Egypt, spices from the East, and slaves from conquered lands flowed into the empire. But as expansion slowed, so did the inflow of wealth. Rome’s economy faced mounting pressures:

Heavy taxation burdened farmers and citizens, discouraging productivity and fueling resentment. Inflation, particularly during the 3rd century, devalued Rome’s currency as emperors debased silver coins to fund wars. The empire relied heavily on slave labor, but as conquests waned, the supply of slaves dwindled, leading to agricultural decline. Trade routes became increasingly unsafe due to piracy, banditry, and invasions, disrupting the flow of goods.

The Roman economy, once the engine of empire, began to falter. Poverty deepened, inequality widened, and the promise of prosperity that had once bound provinces to Rome weakened.

The Burden of the Military

The Roman army was both Rome’s pride and its burden. For centuries, the legions were unmatched, their discipline and organization striking fear into enemies. But maintaining this vast military machine required staggering resources. Soldiers had to be paid, fed, and equipped, and the costs often drained the treasury.

Moreover, the nature of Rome’s enemies changed. No longer facing disorganized tribes, Rome now confronted powerful confederations like the Goths, Vandals, and Huns, who adapted to Roman tactics and exploited weaknesses in the empire’s defenses. To meet these threats, Rome increasingly relied on mercenaries—non-Roman soldiers who were loyal only as long as they were paid. This dependence eroded the discipline and cohesion that once made Rome’s armies invincible.

The empire that conquered the world with its legions eventually found those same legions stretched thin, fragmented, and sometimes even turning against the empire they served.

The Division of the Empire

In 285 CE, Emperor Diocletian made a fateful decision: to divide the empire into East and West. The Eastern Roman Empire, centered on Byzantium (later Constantinople), was wealthier and more defensible, with strong trade routes and fortified cities. The Western Roman Empire, centered on Rome and later Ravenna, was poorer, more rural, and more vulnerable to invasion.

While the division temporarily stabilized administration, it also created imbalance. The East survived and thrived, while the West struggled and weakened. This duality meant that resources were not evenly shared, and when crises struck, the Western Empire often lacked the strength to recover. The fall of Rome in the West would eventually stand in contrast to the survival of the Byzantine Empire, which endured for nearly a thousand more years.

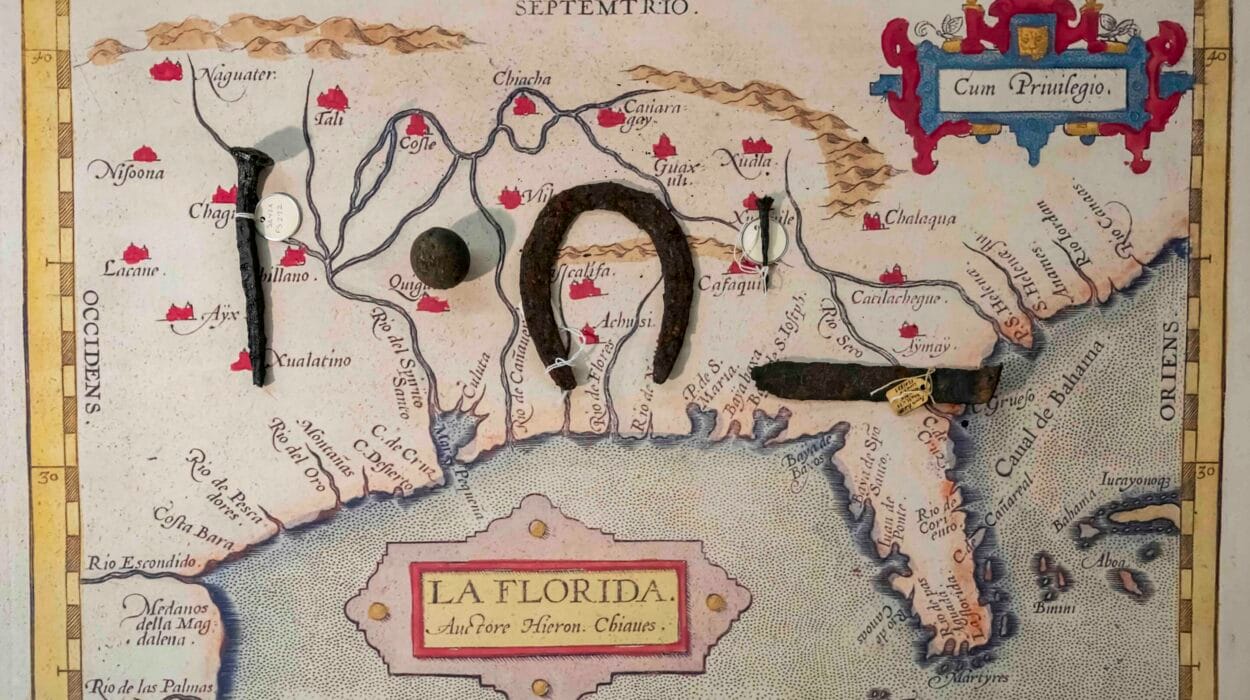

The Barbarian Invasions

Perhaps no factor is more famously associated with the fall of Rome than the so-called “barbarian invasions.” The term “barbarian” was used by Romans to describe non-Roman peoples, particularly those beyond the empire’s frontiers. These groups—Visigoths, Vandals, Huns, Franks, and others—did not simply appear overnight but had long interacted with Rome through trade, conflict, and migration.

The turning point came in 376 CE, when the Visigoths, fleeing the advance of the Huns, sought refuge within Roman territory. Poorly treated, they rebelled, and in 378 CE, at the Battle of Adrianople, they crushed the Roman army, killing Emperor Valens. This defeat shattered the myth of Rome’s invincibility.

In 410 CE, the Visigoths under Alaric sacked Rome itself—a symbolic blow that shook the empire’s foundations. Later, in 455 CE, the Vandals repeated the act, plundering Rome and leaving devastation in their wake. Finally, in 476 CE, the Germanic chieftain Odoacer deposed the last Western Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, marking the traditional date for the fall of Rome.

These invasions were not merely external assaults; they were symptoms of Rome’s weakened state. The empire could no longer defend its borders effectively, and the barbarian groups, once allies and federated peoples within Rome, became conquerors.

The Erosion of Roman Identity

Rome had long prided itself on its ability to absorb and assimilate other cultures. Conquered peoples often became Roman citizens, adopting Latin, Roman laws, and Roman customs. But as the empire aged, this integration faltered. Loyalty to Rome declined as local identities strengthened, especially in the provinces.

The spread of Christianity also transformed Roman identity. In 313 CE, Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity, and by the end of the 4th century, it had become the empire’s dominant religion. While Christianity brought unity of faith, it also shifted focus away from traditional Roman values, such as loyalty to the state and the old gods. Some historians argue that this spiritual transformation contributed to weakening Rome’s civic institutions, though others view Christianity as a stabilizing force during troubled times.

What is certain is that the old idea of Rome—an empire built on conquest, civic duty, and imperial cult—gave way to something new. As cultural and religious identities shifted, the cohesion that had once bound the empire began to unravel.

Environmental and Health Pressures

Rome’s fall was not only political and military but also environmental. Deforestation, over-farming, and soil depletion reduced agricultural productivity in many regions. The reliance on grain imports from Egypt and North Africa made Rome vulnerable to disruptions in supply.

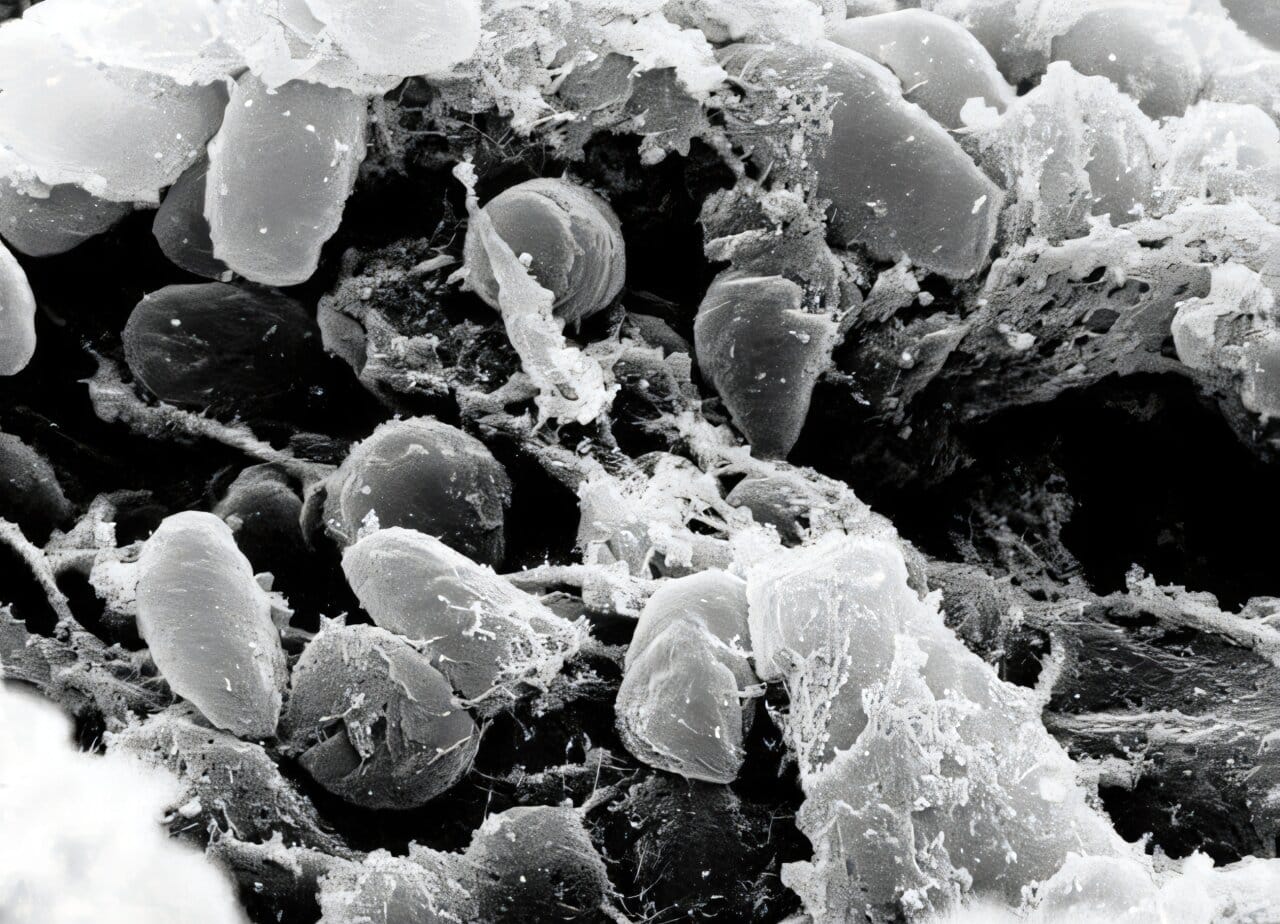

Epidemics also struck the empire. The Antonine Plague in the 2nd century and the Cyprian Plague in the 3rd century devastated populations, killing millions and weakening both the economy and the military. As population declined, so too did tax revenues, manpower for the legions, and the ability to sustain the empire’s vast infrastructure.

Nature, indifferent to human ambition, played its role in humbling the empire that once sought to master it.

Was Rome’s Fall Inevitable?

Historians debate whether the fall of Rome was an inevitable collapse or a transformation into something new. The empire did not vanish in an instant but evolved. The Western Empire disintegrated, but its laws, culture, and traditions lived on in the kingdoms that replaced it. The Eastern Empire, the Byzantine world, preserved Roman identity in altered form for centuries.

Some argue that Rome never truly “fell” but instead transformed into medieval Europe. Roman institutions blended with Germanic traditions, Christianity spread through former imperial lands, and the memory of Rome endured as a symbol of power, order, and civilization.

Yet, the political entity of the Western Roman Empire did collapse. The city of Rome, once the beating heart of an empire, became a shadow of its former glory. The aqueducts broke, the population dwindled, and the marble monuments crumbled.

Lessons from Rome’s Fall

The fall of Rome is not just a historical curiosity—it is a warning and a lesson. It reminds us that no civilization is invincible, that internal weaknesses can be as deadly as external threats, and that the management of resources, leadership, and identity are crucial to survival.

Rome’s story resonates in every empire that has risen and fallen since. It challenges us to reflect on the fragility of human institutions, the importance of adaptability, and the costs of complacency. The collapse of Rome is not just the past—it is a mirror in which we can see echoes of our present and perhaps glimpses of our future.

The Eternal Legacy

Though the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 CE, Rome itself never truly died. Its language, Latin, evolved into the Romance languages spoken today. Its laws influenced legal systems across Europe and beyond. Its architecture, philosophy, and art continue to inspire. Even its political ideals—the Senate, the Republic, the notion of citizenship—echo in modern democracies.

The fall of Rome was not the end of civilization but the beginning of a new world, shaped by Rome’s memory and inheritance. In ruins and resilience, Rome lives on.

Rome once claimed to be eternal. Though its empire fell, in a sense, it was right. Rome endures not as a political entity but as an idea, a reminder of human ambition, achievement, and fragility. The fall of Rome was the end of one world—and the beginning of another.