On the sun-baked plains and savannas of West Africa, an empire once rose that dazzled the medieval world with its wealth, power, and cultural brilliance. The Mali Empire, born in the 13th century, was more than just a kingdom of warriors and rulers—it was a center of gold, scholarship, and spiritual richness that captured the imagination of travelers from Africa, the Middle East, and even Europe.

Stretching across modern-day Mali, Senegal, Guinea, Mauritania, and Niger, the empire was vast, controlling critical trade routes that linked the Sahara Desert to the forests of West Africa. It was not just its size that made Mali remarkable, but its ability to blend military strength, political organization, and cultural achievement into one of the most celebrated civilizations in African and world history.

The story of the Mali Empire is a story of resilience, opportunity, and vision. Born in a landscape both harsh and fertile, Mali grew to dominate West Africa for centuries. Its legacy still resonates, not only in the history books but also in the identity and memory of African people today.

Foundations in the Mandé Heartland

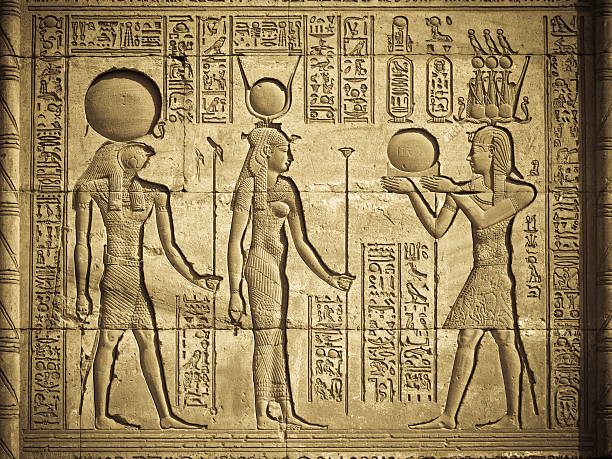

The roots of the Mali Empire reach deep into the soil of the Mandé heartland, a region where agriculture, river trade, and clan-based societies had flourished for centuries. Before Mali, the Ghana Empire (not to be confused with the modern nation of Ghana) dominated the western Sahel. Ghana thrived on trans-Saharan trade, particularly in gold and salt, but by the 11th century, pressures from invasions, internal divisions, and shifting trade routes weakened it.

In this vacuum rose the Mandinka people of Mali. They were farmers, herders, and traders, but also warriors with a keen sense of unity and identity. Oral traditions preserved by the griots—West Africa’s historians and storytellers—describe this formative period as one of struggle and transformation.

At the heart of Mali’s origin lies the story of Sundiata Keita, the “Lion King” of Mali, whose legend has been passed down for generations.

The Epic of Sundiata: A Hero’s Tale

The tale of Sundiata Keita is one of history’s most powerful epic narratives. Born disabled, unable to walk in his early years, Sundiata was underestimated and ridiculed. Yet destiny, as told by the griots, marked him for greatness. Through perseverance, intelligence, and strength, he overcame his disability, rallied his people, and defeated the oppressive Sosso king, Sumanguru Kanté, at the Battle of Kirina in 1235.

This victory was not just a military triumph but a symbolic rebirth of Mandé power. Sundiata unified rival clans under a new vision, laying the foundations for the Mali Empire. He established a system of governance that balanced centralized authority with local autonomy, forging unity in diversity.

Sundiata’s reign became the golden seed from which the empire grew. He is remembered not just as a conqueror but as a lawgiver and a unifier, a leader who turned struggle into strength. His story endures in West African oral traditions, celebrated in epic poetry, music, and cultural memory—a reminder that Mali was as much a civilization of stories and culture as of armies and wealth.

Wealth Beyond Imagination

If one word could capture the Mali Empire, it would be wealth. Mali sat atop some of the richest goldfields in the world, particularly in Bambuk, Bure, and later Akan lands. At a time when gold was the foundation of global commerce, Mali’s resources made it legendary.

Gold was the lifeblood of Mali’s prosperity, fueling its influence across continents. Caravans laden with gold dust crossed the Sahara, bound for North African cities like Marrakech and Cairo, and from there to Europe and the Middle East. Mali’s wealth was so immense that when its rulers spent or gave away gold, it disrupted economies thousands of miles away.

But gold was not Mali’s only treasure. Salt, mined from the arid depths of Taghaza and Taoudenni, was equally valuable, especially in a hot climate where salt preserved food and sustained life. Ivory, kola nuts, slaves, and textiles also flowed through Mali’s markets. The empire’s control of trade routes ensured it profited from the exchange of both goods and ideas.

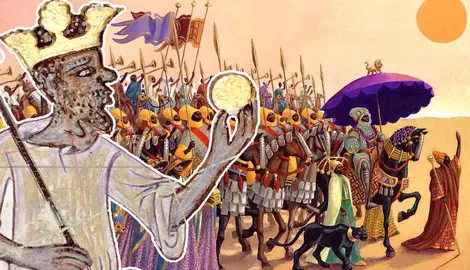

The Glory of Mansa Musa

No discussion of the Mali Empire is complete without Mansa Musa, its most famous ruler. Ascending the throne in 1312, Musa Keita I inherited a prosperous kingdom, but his reign elevated Mali to unprecedented glory.

Mansa Musa is remembered most for his legendary pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324. With a caravan reportedly numbering tens of thousands, including soldiers, officials, and attendants, he traveled across the Sahara carrying staggering amounts of gold. In Cairo, his generosity was so overwhelming that the value of gold reportedly plummeted for years, creating economic ripples across the Mediterranean world.

But Mansa Musa was not merely a symbol of wealth. He was also a patron of learning, architecture, and religion. Upon his return, he commissioned the construction of mosques, libraries, and schools, transforming cities like Timbuktu and Gao into centers of Islamic scholarship. Under his reign, Mali became not only an economic superpower but also a beacon of culture and intellectual achievement.

Timbuktu: Jewel of the Niger

Few cities in world history evoke as much wonder as Timbuktu. Situated on the Niger River, it became Mali’s crown jewel—a city where trade, learning, and spirituality converged.

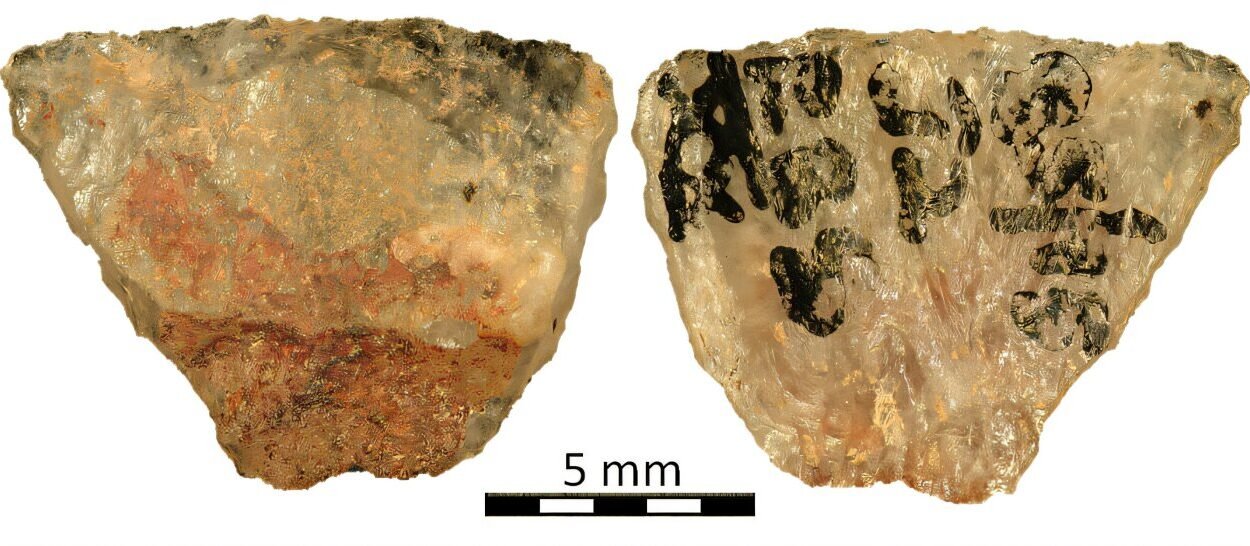

Timbuktu’s markets bustled with traders bringing gold, salt, books, and textiles. Its mosques, such as the famed Djinguereber Mosque built with Mansa Musa’s patronage, stood as architectural marvels of mudbrick and timber. But its greatest treasure was knowledge. The city’s scholars copied manuscripts, taught students, and debated theology, astronomy, law, and medicine. The University of Sankoré became a hub of learning that attracted intellectuals from across Africa and the Islamic world.

In Timbuktu, ideas traveled as freely as gold, and its libraries housed tens of thousands of manuscripts—many of which survive today as priceless artifacts of human thought. The city symbolized the intellectual soul of Mali, reminding the world that African civilizations were not only wealthy but deeply scholarly.

Governance and Society

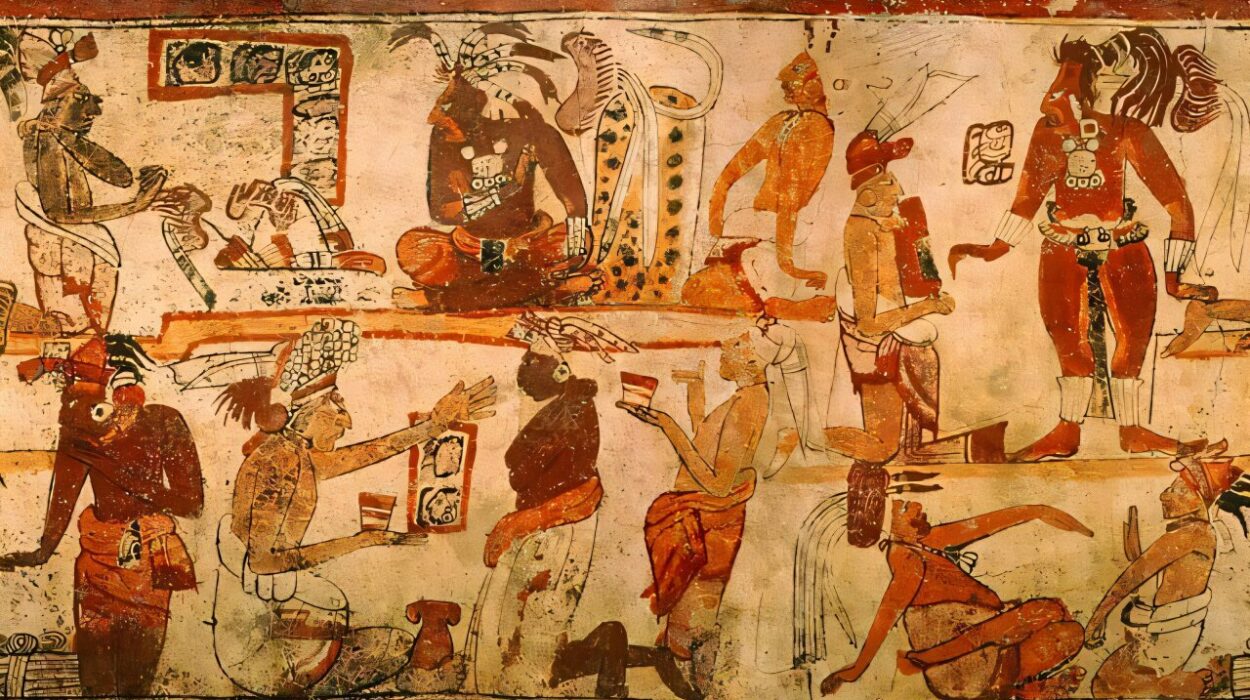

The Mali Empire was more than kings and wealth—it was a complex society with a structured system of governance. The emperor, or Mansa, wielded supreme authority, but local leaders, clan chiefs, and officials played vital roles in administration. Sundiata’s system of laws, known as the Kurukan Fuga, created a balance between central power and local traditions.

Society was hierarchical but interconnected. Nobles, warriors, merchants, farmers, and artisans all had roles. The griots, or jeliw, were especially significant—they preserved history through oral tradition, ensuring that Mali’s legacy survived in memory and song.

Religion added another layer of identity. While Islam became the state faith of rulers like Mansa Musa, traditional beliefs endured among much of the population. This blending created a unique cultural synthesis, where mosques stood alongside sacred groves, and Quranic learning coexisted with ancestral rituals.

Decline of the Empire

All empires, however, face decline, and Mali was no exception. After the reign of Mansa Musa, succession disputes weakened the central authority. Provinces broke away, and rival states rose. The Songhai Empire, once a vassal of Mali, grew powerful and eventually eclipsed Mali by the late 15th century.

External pressures also played a role. Tuareg invasions threatened trade routes, while shifts in commerce toward the Atlantic coast reduced the importance of trans-Saharan trade. By the 16th century, Mali’s golden age had faded, though fragments of its power lingered.

Yet decline did not erase Mali’s legacy. Its memory endured in the oral traditions of West Africa, in the manuscripts of Timbuktu, and in the chronicles of Arab historians who marveled at its splendor.

Legacy of Gold and Glory

The Mali Empire’s legacy is vast and enduring. It showed the world that Africa was not a “dark continent” but a land of brilliance, wealth, and culture. Its gold fueled global economies, its scholars enriched Islamic learning, and its stories inspired generations.

Even today, the name “Mali” carries echoes of grandeur. The modern Republic of Mali draws its name from this empire, a reminder of its proud heritage. Across West Africa, griots still sing of Sundiata and Mansa Musa, keeping alive the memory of a civilization that once shone like gold in the desert sun.

Conclusion: Mali’s Place in World History

The Mali Empire was not an isolated kingdom on the edge of the world but a vibrant participant in global history. Its wealth reached Europe and Asia, its scholars influenced Islamic thought, and its leaders left legacies that rival those of any medieval monarchs.

To speak of Mali is to speak of resilience and imagination, of a people who turned the challenges of their environment into opportunities for greatness. It is to honor the gold that sparkled in their rivers, the stories that echoed in their songs, and the glory that once made West Africa the envy of the world.

The Mali Empire’s story reminds us that history is not only written in stone palaces or on parchment scrolls but also in the hearts of those who remember. And as long as the griots sing, the empire of gold and glory will never truly fade.